16 November 2021. Flow | Debt

The psychology of flow and optimal experience. Getting rid of predatory debt.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The psychology of flow and optimal experience

The website Edge has posted some material to mark the death of the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He’s best known for his work on flow, which I first came across when I was working on interactive television in the 1990s.

It’s a simple model, and once learnt, unforgettable: as we gain competence at something, our learning performance needs to stay within fairly narrow bounds. Too easy, and we get bored. Too hard, and we get anxious and frustrated. Here’s the version on Wikipedia:

(Image by Wesley Fryer via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0)

So A1 and A4 are both good (A4 is better, because you’re performing at a higher level. A2 is not so good—the level of challenge isn’t high enough, and you get bored. A3 isn’t good either—the level of challenge is too high for your skill level, and you get anxious.

There are obvious implications for game design, but pretty much all learning falls into this pattern.

Edge re-shares a wide-ranging conversation with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi that it published in 2004. The video version is 39 minutes, and there’s also a transcript, from which these extracts are taken.

First, it was one of those ideas that he’d had very young:

If I were to try to go back to the origins of the theory, I would say that it probably started germinating in 1944-45, when I was ten years old. At that time the war was creating a lot of anxiety everywhere... I realized, however, that when I played chess, I completely forgot what was going on, and for hours I had a great time. I felt completely involved, my mind was working, I had to be alert, and I had to process information about what was happening... I also noticed then that if I played against somebody really good, it wasn't much fun. If I played against somebody who played badly, it wasn't fun either because I started getting distracted and thinking about other things. But if my opponent was somebody in my own range of abilities, then the game was fun.

At the end of the war his family moved from Hungary to Italy, and then he moved to the USA to study psychology. He was disappointed by the Amercian approach to it:

Essentially all psychology was focused on pathology. When you looked at normal behavior it was always reduced to some pathology, or it was considered something that you learn like rats in a maze. There was no notion that people could actually enjoy life.

But as he started teaching, he was lucky enough to find a group of really smart graduate students who started to explore the experience of all sorts of activities, from rock climbing to dancing to surgery.

(W)hat I found was that, in fact, surgeons described doing surgery very similarly to the way musicians described making music, or artists described painting, or poets described writing poetry. Out of all this came the notion that it's not really play that makes you feel good, but the playfulness which can be in play. Whether you find it in a job or a religious experience, there is a kind of experience underlying all of these different activities which is so positive that you want to do it over and over again, even though there is no benefit except the experience itself.

From that, he also got involved with the project that Martin Seligman developed around the idea of “positive psychology”. That idea has its critics, of course, but nonetheless it represents an attempt to build a set of psychological practices that aren’t just about pathologies: “a notion”, says Csikszentmihalyi in the interview, “that there are human strengths we need to understand—not just sicknesses”.

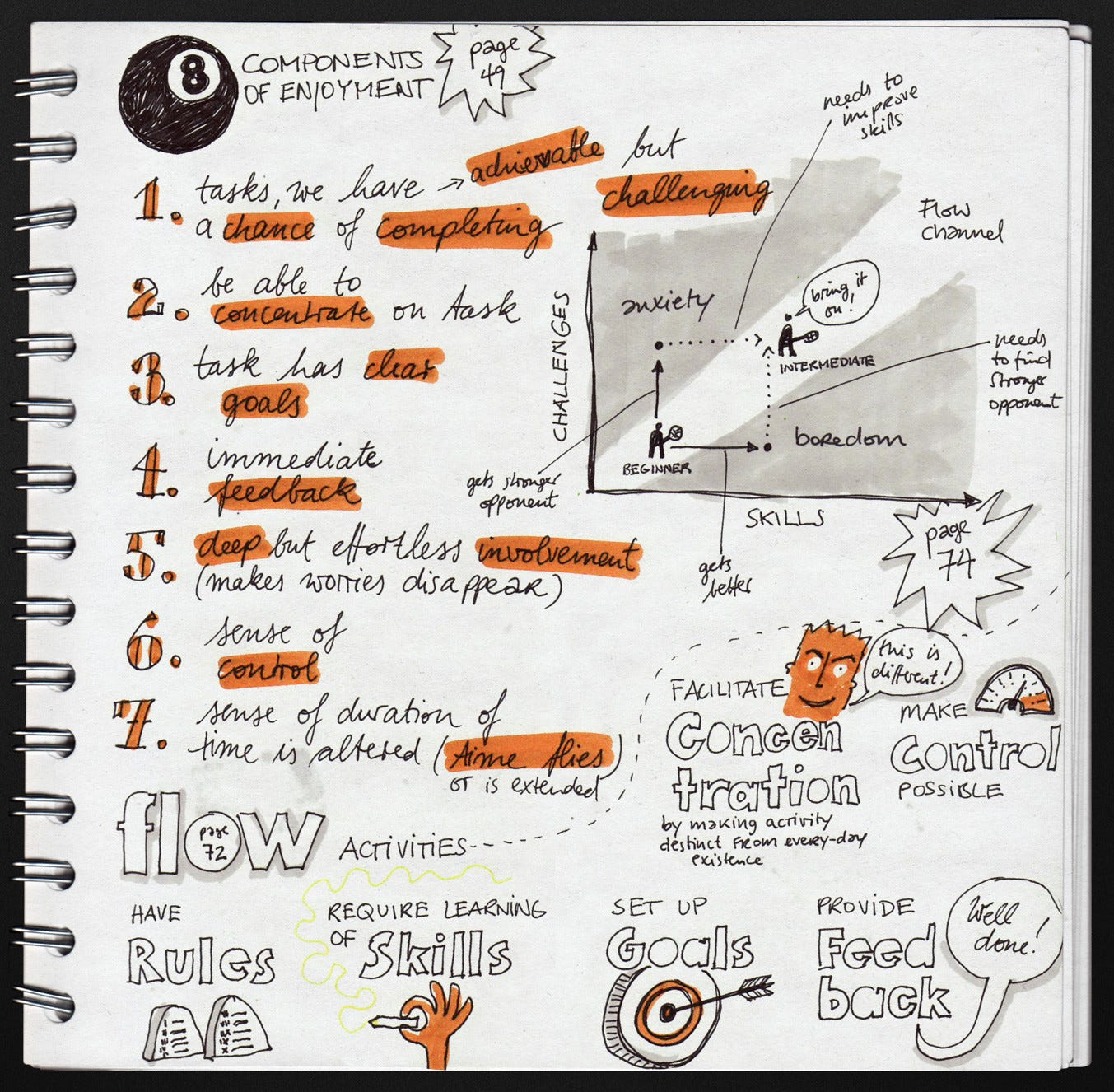

While doing the research for this Thing, I also came across some sketchbooks by Eva Lotte Lamm that summarised the book, which looked like fun:

(Notes on flow, by Eva Lotte Lamm. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

There’s also an introduction to his book on this subject on ResearchGate if you want to find out more.

#2: Getting rid of predatory debt

Debt is one of those subjects that makes people glaze over. People get into debt, they need to repay it, right? Well, not so fast. Because as David Graeber explained to us a while back, debt is actually a set of social and economic agreements, usually embedded in social institutions, and these agreements can be rewritten if need be.

Which is a long way into a short note on the fact that New York City has just ended a long-running dispute with its taxi-drivers over the levels of debt the drivers were carrying to pay for the taxi medallions that allow them to drive a New York cab.

(Photo by Danielle Lupkin, via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

These levels of debt weren’t trivial. The 4,000 owner-drivers each carried an average of $500,000 of debt, against medallions that are now worth around $120,000, post-Uber, post-Lyft. Some drivers had committed suicide under the weight of them. As the Next City article reports:

“Of all the factors of poverty, debt is the one where people feel like they’re in an underground mine and there’s no hope left,” says Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, the driver union behind the plan. “We think this could be precedent-setting.”

The drivers have had the upper hand, morally at least, since a New York Times investigation found that New York City had conspired with lenders in the early 2000s to push up the price of the taxi medallions. But what’s more interesting is that way that the city authorities structured the deal so that both lenders and borrowers were happy with it.

Most of the drivers’ debts had been been held by a group of credit unions. But last year the relevant regulatory agency shut down a number of these, alleging in at least one case a “breach of duties”. It took on the loan book itself before selling it on.

Now debt never gets sold on at face value. The buyer makes a calculation about how much of it they are ever like to be able to recover, and makes an offer that’s worth so many cents on the dollar. So if the loan book has a face value of say $1 million, and the buyer thinks they’ll be able to recover more than $150,000 of it, they’ll bid 15 cents on the dollar, or so.

And suddenly, this debt is worth a lot less. It’s just become fungible. And it’s this that makes it possible to restructure the debt. And one of the interesting elements is that the plan was developed by the New York Taxi Workers Alliance.

There’s three elements here, as the Next City article explains, and effectively they are locked together.

First, the lender accepts that the portfolio of loans isn’t worth its face value, and it reduces the debt held by each of the drivers. At the same time the city underwrites the loan book, turning a pile of debt which is going to be hard to recover, and uncertain in its returns (and also reputationally damaging) into a guaranteed income stream.

For the drivers, their $500,000 loans have become $200,000 loans, which they can afford the repayments on.

The city has also granted the drivers a $30,000 down payment, which means that the maximum monthly repayment is now $1,100. And, additionally, because it’s underwriting the loan, drivers are no longer at risk of losing their cabs, or their homes, if they fall behind with payments.

The Taxi Workers Alliance worked with advisers to design an agreement that had something in it for everyone:

“We worked with financial advisors to come up with a plan that would bring lenders to the table,” Desai says. “We had Zoom calls with screen sharing looking at excel models of the risk-sharing. We would look at the loan amortization schedules with people throwing out numbers.”

The cost of all of this is estimated at $100 million, which is coming from the funds released under the American Rescue Plan Act. New York Senator Chuck Schumer encouraged the city to take the plan seriously. And that $100m figure is tiny compared to the $1.2 billion of debt hanging over the drivers before.

There’s lot of debt out there that’s never going to get repaid at face value—Britain’s student loans, to take one example. As Desai says, it weighs hugely on the individuals holding it. It’s better for everyone—lenders included—if it becomes a collective responsibility.

j2t#208

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.