16 March 2022. Trust | Search

Looking at Edelman’s 2022 trust data isn’t reassuring. Google Search is dying, at last.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Looking at Edelman’s 2022 trust data isn’t reassuring

I’ve been meaning to write about the 2022 edition of Edelman’s Trust Barometer ever since it came out at the end of January. Since it seems to be something of a piece with the V-Dem Democracy Index, which I wrote about yesterday, today seems to be a good day.

The numbers: they survey 36,000 people globally, across 28 countries; although this seems a lot, the average national sample is 1,150, which means that small changes in year on year trends for individual countries need to treated with a little caution. The fieldwork was done in November last year.

But: they’ve been doing this for a long time now—it’s in its 22nd year—and deserve some credit for sticking with it, although since it’s the only reason why pretty much anyone has heard of Edelman it can’t be the hardest business decision they make each year. This does also mean that some of their longitudinal research now has some value.

First, year on year, trust in business is flat; NGOs are up a little; government and media down a little. (The headline, that ‘business is still the only trusted institution’, is because Edelman has a convention that ‘trust’ kicks in at 60%, and ‘distrust’ when you fall below 50%.) And this chart—the first in the full report, is also a bit of a shocker, from a research reporting point of view, since the higher figures over to the right, from May 2020, are from a subset of the countries in the overall ‘Global 27’ countries that are in their research set. So ignore the comparison.

But the main point here is that there’s a distinct difference in global trust levels between business and NGOs on the one hand, and government and media on the other.

The reason for this might be that, according to their data, business and NGOs are seen as a unifying force in society, while government and media are seen as divisive, and the way Richard Edelman summarises this in his narrative is:

The media business model has become dependent on generating partisan outrage, while the political model has become dependent on exploiting it. Whatever short-term benefits either institution derives, it is a long-term catastrophe for society. Distrust is now society’s default emotion, with nearly 60 percent inclined to distrust.

This might also be connected to a further data point: concern about fake news is at an all-time high, and increased last year in all but three of the countries for which they have comparative data.

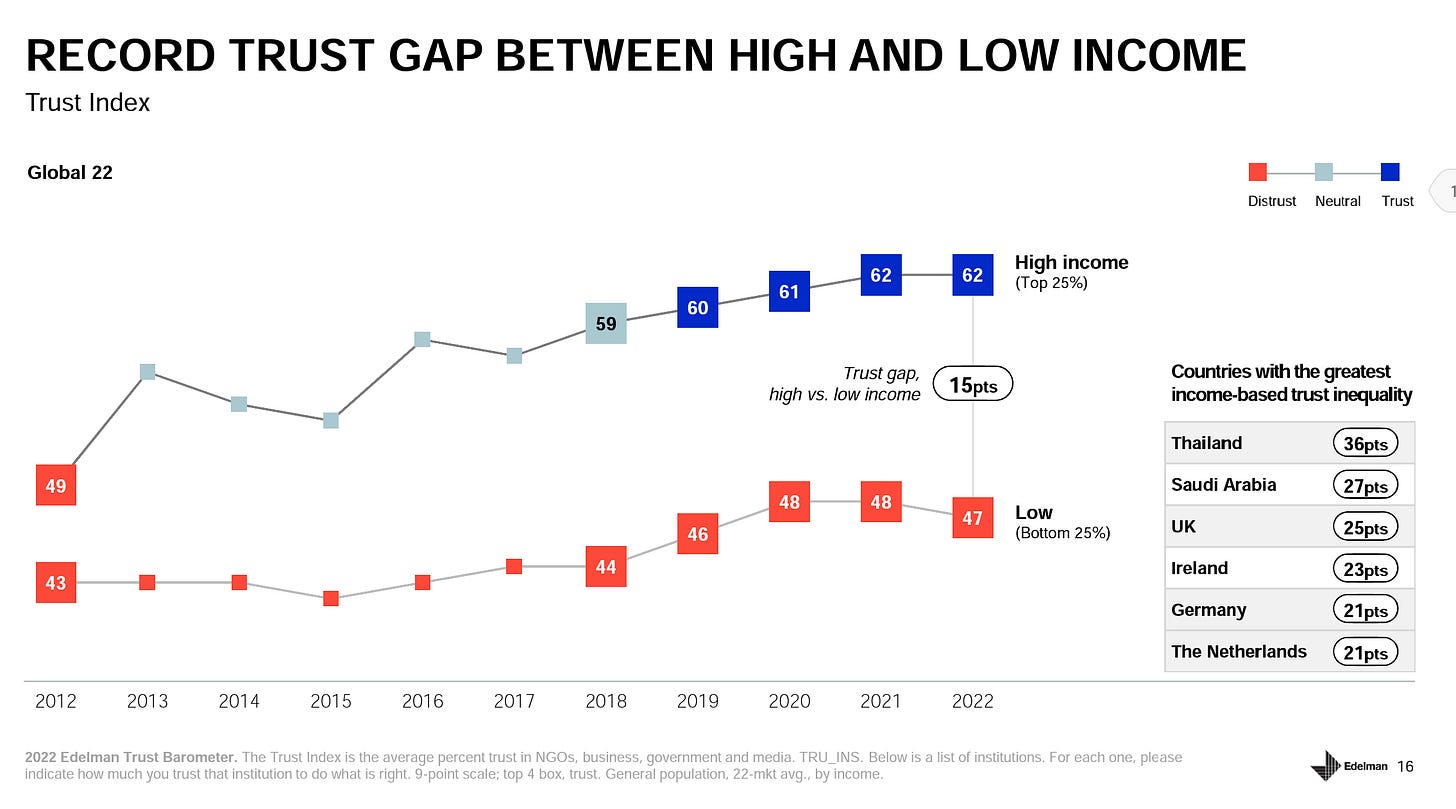

There’s also a large trust gap between high income and low income respondents. Edelman describe this gap (15 percentage points) as being a ‘record’, and so it is, but in truth it’s been bouncing around at about the same level for half a decade now. There’s some clues in the data as to why this might be: in the richer countries surveyed, without exception, less than half of respondents believed that they would be better off in five years time.

There is a small flicker of good news here: this gap closes for people who are well informed, and quite sharply. There might be some hope that better quality media and more media literate populations might increase trust levels a bit.

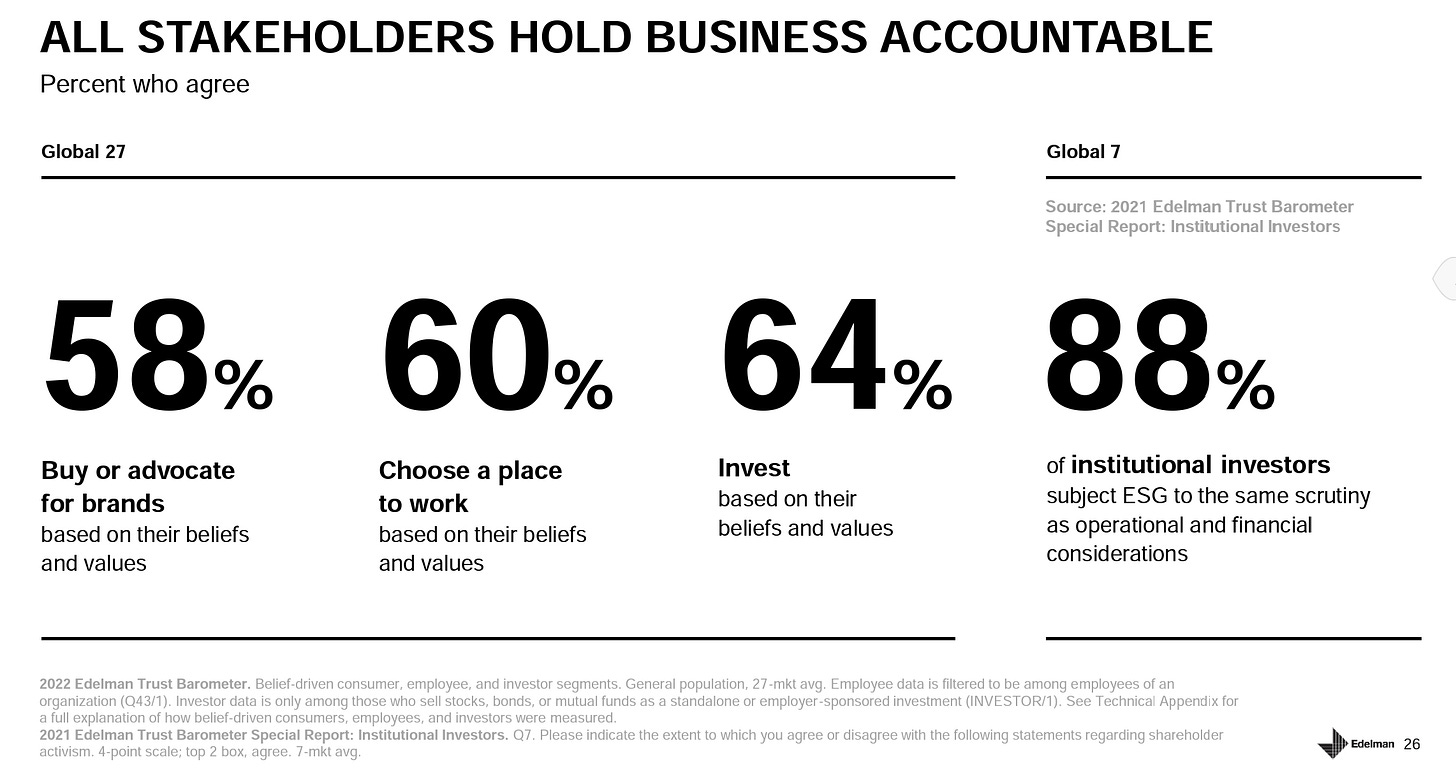

The other story in here is that people expect businesses to play a role in society and make choices about where they work, who they buy from, and how they invest, based on their values. I’m always slightly suspicious of data like this, because it’s an easy thing to agree with in a survey, but these are high numbers. I’m assuming that there aren’t year-on-year comparisons here because they didn’t ask these questions last year.

This is Edelman’s home turf, and this is where a lot of their business comes from, so they have an interest in playing this up, but allowing for this, here’s Richard Edelman’s story about this:

the Trust Barometer shows that, by an average five-to-one margin, respondents want business to play a bigger, not smaller, role on climate change, economic inequality, workforce reskilling and racial injustice. Every stakeholder group expects business to lean in—nearly 60 percent of consumers now buy brands based on beliefs while 6 in 10 employees choose a workplace based on shared values and expect their CEO to take a stand on societal issues.

I’ve seen hints recently that there’s a pushback around ideas of purpose-driven business, which I’ve been meaning to research, but this data suggests that this pushback might be coming from vested interests rather than representing an underlying shift in sentiment.

The whole story here is problematic. The vicious cycle between government and media is destabilising first of trust and then of institutions. There are some clues to a solution—some of the data suggests that people are fearful about a host of things, including climate change, unemployment or economic insecurity, inequality, and discrimination.

The report proposes a complicated story in which the higher trust institutions—business and NGOs—somehow hold the ring while government and media improve. I think there’s a simpler version: for government to step up and do something meaningful about climate change, to improve economic security, reduce inequality, and reduce discrimistion.

Finally, when the Trust Barometer was published, I saw several people tweet or comment that ‘technology’ companies weren’t seen as a problem and that fears of a so-called ‘techlash’ must therefore be overblown. Maybe they didn’t manage to read all the way across to the right hand side of the chart. I’d say this was consistent with the rest of the data here.

And I think we can agree that the global experiment of having our media and public information channelled through organisations that have no interest in it other than as a tool to drive advertising revenues has now failed.

2: Google Search is dying, at last

On that note, it seems like a good moment to mention a piece that argues that Google Search is dying. The original post has been amplified in mainstream media (in The New Yorker and Fast Company) but I traced it back and the original—by DKB, aka David Brererton—has a zip and directness than gets lost in the coverage. Also: support your local blogger.

Obviously Google Search is heavily used, by hundreds of millions of people, and—if it is dying—will take a long time to go. But:

If you’ve tried to search for a recipe or product review recently, I don’t need to tell you that Google search results have gone to shit. You would have already noticed that the first few non-ad results are SEO optimized sites filled with affiliate links and ads. Google still gives decent results for many other categories, especially when it comes to factual information.

DKB is not alone in thinking this—he links to a host of people, including the tech investor Paul Graham, who have noticed much the same thing. Their general view is that Google is open to disruption by a new entrant.

(A search for ‘washing machines’. Just now)

Why should Google Search be poor? Well, making money from advertising creates the wrong incentives. Of course, that was the exact insight that Brin and Page had when they founded Google, which is worth quoting here from DKB’s blog post:

“Currently, the predominant business model for commercial search engines is advertising. The goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users…we expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers…Furthermore, advertising income often provides an incentive to provide poor quality search results.”

Other reasons include people gaming the SEO (search engine optimization) system and Google AI systems (or more exactly, machine learning) that try to guess what you actually meant rather than believing what you typed in.

One of the consequences of all of this is that our information is in a sea of bots, or people who are behaving like bots because that’s the best way to maximise their gains from the web. Quoting IlluminiPirate:

TLDR: Large proportions of the supposedly human-produced content on the internet are actually generated by artificial intelligence networks in conjunction with paid secret media influencers in order to manufacture consumers for an increasing range of newly-normalised cultural products.

And one of the unexpected effects of this is to fuel the growth of Reddit as a platform. It’s not a search engine, and it doesn’t want to be a search engine, so it’s the best place to go to find human opinions about products and services:

So how can we regain authenticity?...

You append “reddit" to your query (or hacker news, or stack overflow, or some other community you trust).

Google is dead.

Long live Google + “site:reddit.com”.

Until the bots get there, of course.

Ukraine notes

Thanks to Kai Brach at Dense Discovery for his piece about the current work of the Ukrainian artist, photographer and writer Yevgeny Belorusets. She is based in Kyiv and has been keeping a war diary since the invasion. Here’s an extract from Kai’s piece:

Through her short daily entries, she paints an intimate, at times hopeful, often upsetting but always human picture of what it’s like living with the ever-present anticipation of violence and destruction.

“When I left my apartment today, I saw an empty street. No cars, no pedestrians. At such moments, Kyiv seems like a city that has yet to be inhabited – a city without a present, with only a past and a future. …

You can subscribe to Yevgeny Belorusets’ newsletter here. As Kai Brach says,

I hope Belorusets’ daily writing will continue. I hope she can keep documenting the lived experience of this war and, by doing so, remind us of the preciousness and precariousness of the lives we all live. Most of all, I hope she will be okay.

j2t#280

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.