16 June 2023. Water | Paleofutures

Saving Spain’s ancient irrigation systems // Back to the future—the year 2000 as seen from 1979. [#467]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend!

1: Saving Spain’s ancient irrigation systems

My wife returned from Granada with pictures of the ancient acequia water system that the Moors built in southern Spain more than a thousand years ago. It’s been in decline since the 1960s. The word comes from the Arabic as-saqiya, meaning “water conduit” or “water bearer”.

Parts of it have been threatened, by road-building, by the abandonment of some of the more remote villages that used to maintain parts of the system, and by the different irrigation methods used by modern intensive farming. But there are various projects in hand that have been working or repairing and restoring the system.

All of this reminded me of an article by the futurist Jim Dator (not to hand right now) which suggested that the future came from three places: things in the present which were already happening; ‘novelties’ in the future that we couldn’t yet imagine; and things from the past that had become submerged that were now reappearing. Perhaps literally, in the case of the acequia.

(An acequia in the streets of Pampaneira. Photo by Sue Robinson. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A recovery project (website in Spanish), which has been cleaning out disused acequia and re-connecting them, run by the University of Granada, got some media attention last year. It started almost a decade ago in Cañar, in the Alpujarras mountain region of Granada, as El Pais reported (in English):

“The university provided resources and groups of volunteers and the irrigation community housed them in a local farmhouse and lent them materials,” says Cayetano Álvarez, president of the Cañar irrigation community whose two-hectare garlic and beans farm was one of the many that benefited from the water...“When the water began to flow along it for the first time in 30 years, we held a party – the water festival – which we have repeated every March since.”

Maintaining the water channel requires the collaboration of the entire community. They share the work—and also the water rights. The knowledge they have built locally has extended beyond the area. Villagers have contributed to the recovery of more than 80 kilometres (50 miles) of acequia. In the Sierra Nevada, the network involves 3,000 kilometres (1,800 miles) of water channels. Across Granada and Almeria, there are 24,000 kilometres (16,000 miles).

The acequia date from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Following the Moorish victory in southern Spain, they built the water channels, based on designs that were then common in Syria and Arabia. The region still had Roman aqueducts carrying water, but the difference was that the acequia were designed in the service of agricultural production:

The irrigation channels, the drainage systems and the dams not only made it possible to adapt new tropical crops to the Mediterranean climate, such as citrus fruits, sugar cane, cotton, rice, artichoke and spinach, they also facilitated diversification and increased productivity, generating an essential surplus for the development of industry and trade in cities like Almeria and Granada.

One example of diversification, referenced by the medieval historian and archeologist José María Civantos, who has been involved in the Granada University project, was the cultivation of mulberry trees and the silkworm, which meant the area exported thread and fabric across the Mediterranean. This industry collapsed after the Moors were expelled from Spain.

The water management practices involved are quite sophisticated, according to an article in the BBC’s Future Planet series:

Each year, when the warmth of spring returns to the Sierra Nevada and the thaw begins, snowmelt is diverted from the headwaters of rivers into earthen, porous channels dug into the mountainside. As water flows through the gently descending acequias, ranging in length from tens of metres to kilometres, it's diverted to areas along the upper valley known as simas, where the channel empties and seeps into the ground, a process known as " sowing water". As water percolates through the subsoil, it replenishes aquifers and feeds springs and streams that emerge further down the mountain.

Aquieros, who understand these underground flows, help to maintain the existing system. Research has found that the network of channels improves the flow of rivers and is highly effective at recharging the aquifers, by drawing on ecological principles of water management:

Research has also demonstrated how sowing water doubles the recharge of water in aquifers. The system follows the principles of ecohydrology , which uses "the regulating effect of vegetation, soil and aquifers, imitating nature to regulate water, instead of building concrete structures that alter the flow of water upstream and downstream,"

according to Sergio Martos-Rosillo, who is a hydrogeologist at the Spanish Geological Survey.

(An acequia near Elche. Photo by François Molle/IRD, via Wikimedia. CC BY 2.0)

The acequia system is one of the reasons why it is possible to live in some of the villages in the Sierra Nevada, and this is going to become more true in a world of climate emergency. But it remains undervalued. Traditional agriculture is less profitable than intensive agriculture, even while being more sustainable in this part of Spain, which is one of Europe’s most climate-vulnerable regions. The ecological benefits, and the resilience the system brings, are largely ignored. The villages are still depopulating, which means that nurturing the knowledge held by the aquieros is a battle. There is no money. The recovery work is being done on a shoestring.

As in many other areas, it turns out that deep historic knowledge is going to be essential to maintaining fragile systems in the face of climate change. And that we’d better hope that we notice this in time. Says the historian José María Civantos:

“It is also about the social recognition of rural areas, agricultural activity and local knowledge, which is scientifically valid in most cases, all of which generates landscapes with cultural and environmental value – immense resources that are key to guaranteeing our future as a species.”

2: Back to the future—the year 2000 as seen from 1979

The arrival of this may have been the high point of my week. Usborne has just republished its Book of the Future, which first appeared in 1979. And it is re-published pretty much as it was then, apart from a short introductory note by Tom Cheesewright embedded on the inside front cover. This is obviously a cost-effective publishing strategy, although I don’t know whether the typo on page 84 was in the original or has crept in during the republishing process.

And so, over about 100 or so highly designed paged, we get a section on the future of robots, another one on the future of cities, and then, inevitably, a third section on the future of space (although there’s also quite a lot in there about the future of transport).

Cheesewright was three when his mum bought him his original copy, at a book fair in a church hall in Ealing, in west London:

I spent my childhood in space, in a world of robots and rockets, lightspeed and lasers. It was all in my imagination, fuelled by films, shows, comics and novels. But one thing made it real: the Book of the Future showed me that the fantastic visions I saw on screen were not just fantasy, that through science and engineering, we could turn sci-fi visions into reality - and I could be part of it.

Looking through it, it’s fair to say that the book is over-excited by the prospects for robots, especially robots in space, and also a bit over-excited by space in general. We don’t yet have “Armstrong, the first city on the Moon”, and it is not yet hosting the First Interplanetary Olympics—scheduled here for 2020.

It also falls into the trap of anticipating that some of us would be living and working in ocean-based cities. I’m not going to blame them for this. Reputable futurists queued up in the 1960s and 1970s to talk about our future watery and underwater life, to the point where I suspect the researchers would have felt remiss if they hadn’t included something about it.

(Copyright: Usborne Publishing Ltd. Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The quirkiest thing I found as I leafed through it was a cunning scheme to propel high speed trains on coal, using coal to generate jet-powered thrust:

The fluid-bed furnace is one solution to the problem of powering tomorrow’s trains...crushed coal is fed into a sand-filled firebox, while jets of scorching hot air vibrate and support the sand/coal mixture. Burning coal in this way is very efficient, giving off little or no pollution and generating great heat... Whichever system is used, the outlook for coal as a power source is bight—experts estimate that the world’s coal supplies will not run out for 1,000 years.

There’s also a ‘bullet-shaped train’ in a ‘supertube under the ground’, that is a salutary reminder that the idea of the hyperloop has been around for a long time.

But some of the underlying themes are right. The computing sections—relatively forecastable in 1979–are reasonably familiar, including the smart watch, which they call a “risto’. I’m missing the drinks-serving domestic robot which is promised here, though.

Like a lot of people in the later 1970s, it was worrying about the challenges of feeding a global population of six billion, and the highly mechanised farm of 2020 is a true horror. It knows that materials matter—and, like some of the current rhetoric about the future economics of space, thinks that space mining and space manufacturing might be a solution.

They’re big fans of hydrogen as an energy source, which is also a reminder that technology changes that also require fundamental changes to infrastructure systems always take longer than you expect. And they’re recklessly confident about the arrival of nuclear fusion.

But it’s not all technological wonder. There’s an interesting spread that contrasts two versions of the future city, one grimly polluted Blade Runnertype environment, the other cleaned and greened.

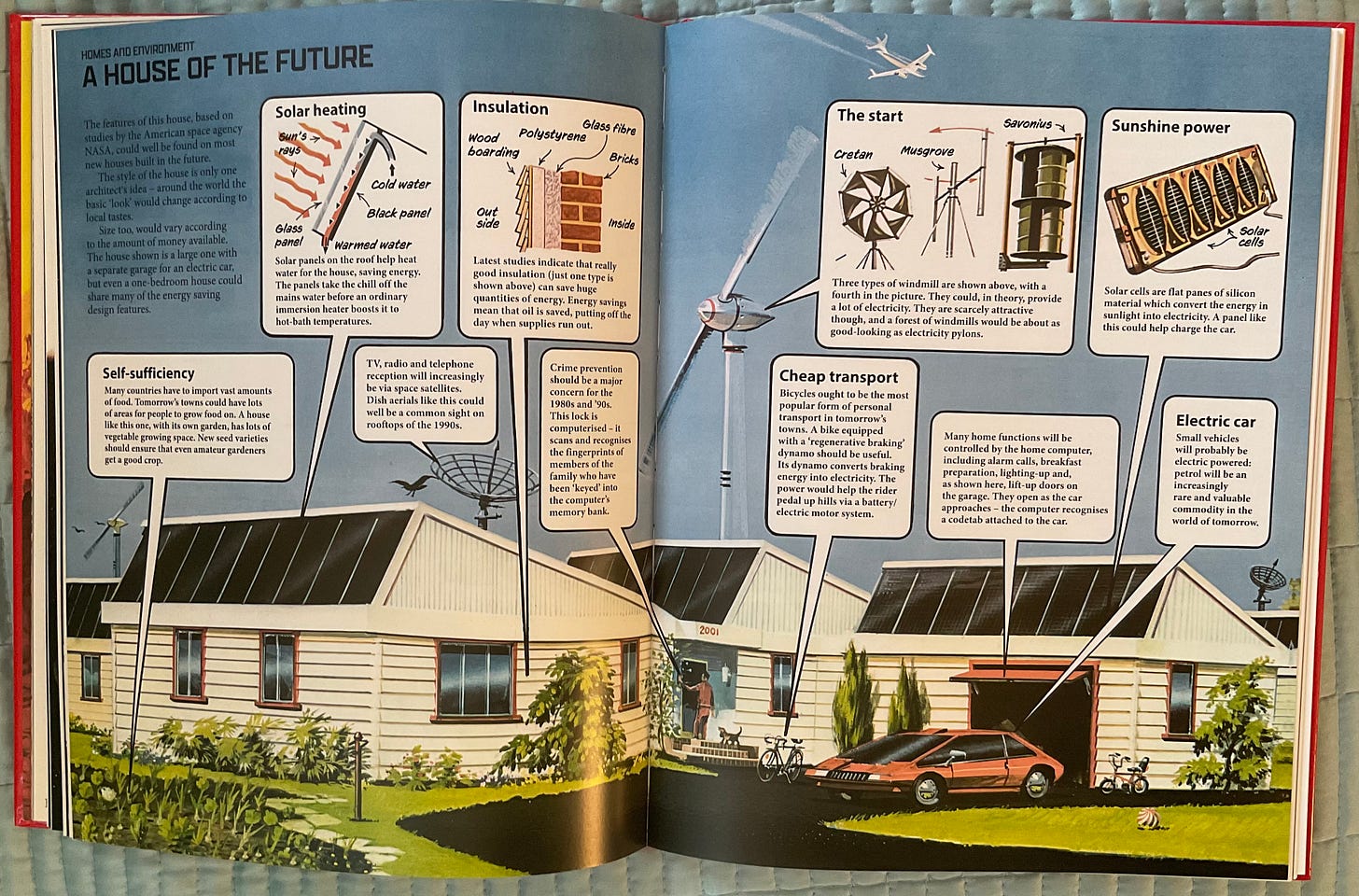

(Copyright: Usborne Publishing Ltd. Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The sections that have probably held up best are the ones about the house of the future. It is reasonably ecological, with solar panels, communications via satellite, and a couple of bicycles propped up outside. Hybrid and electric vehicles get a look-in. This, of course, is a grim reminder that in the 1970s we knew pretty much everything we needed to know to transform our living systems for the better, including the dimensions of the possible crisis, but our political elites instead decided to sponsor a 25-year consumption binge in the name of trickle-down economics.

And, as ever with looks at the future, the social change is missing. Most of these pictures are about tech, so there aren’t a lot of people in them. But there aren’t many women at all. And some of the hairstyles are a disgrace.

All the same, the over-arching effect of looking at The Book of the Future is to recall the late and lamented David Graeber’s essay ‘Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit’ published a decade ago in The Baffler. By 1979, the future was already closing down around us: the ambition that we might be able be able to transform the world for everyone had all but gone. The Book of the Future is at least trying to have a conversation about technological possibility.

But as Graeber wrote, in 2012:

Where, in short, are the flying cars? Where are the force fields, tractor beams, teleportation pods, antigravity sleds, tricorders, immortality drugs, colonies on Mars, and all the other technological wonders any child growing up in the mid-to-late twentieth century assumed would exist by now?... I remember calculating that I would be thirty-nine in the magic year 2000 and wondering what the world would be like. Did I expect I would be living in such a world of wonders? Of course. Everyone did. Do I feel cheated now? It seemed unlikely that I’d live to see all the things I was reading about in science fiction, but it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t see any of them.

j2t#467

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.