16 August 2021. Climate | Drones

The bad faith climate sceptics come out of the closet; maybe the drone revolution isn’t

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

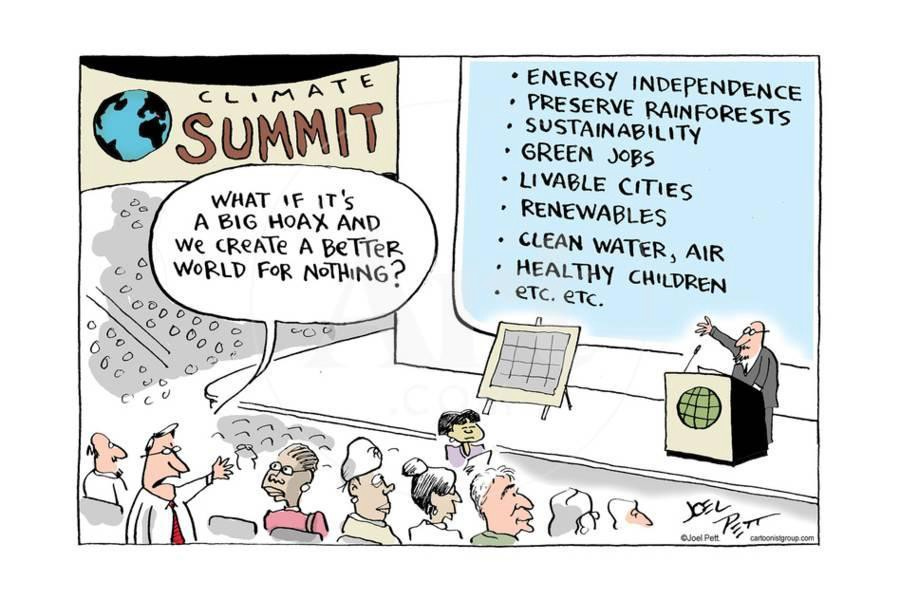

#1: The bad faith climate sceptics come out of the closet

Somewhere in the film The Philadelphia Story James Stewart says:

“The prettiest sight in this fine pretty world is the privileged class enjoying its privileges.”

For some reason this quote came into my head a few days ago when reading Aaron Thierry’s impressive long Twitter thread detailing the line of people who have popped up in the pages of Britain’s right wing newspapers and magazines, since last week’s IPCC report, to explain the reasons why it would be impossible, or undesirable, to do anything about climate change. (No surprise, but spurious cost arguments get quite a lot of airplay, along with quite a lot of whataboutery about China.)

They are the usual suspects, in the usual places: Ross Clark, Dominic Lawson, Dan Wooton, Stephen Glover, Matt Ridley, Allister Heath, Ian Martin, writing in, oh, The Spectator, The Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph, the Sun, the Daily Express, the Times.

You might, by the way, notice some characteristics that this group of affluent older white men have in common.

In his Twitter thread, Thierry draws on the work of William Lamb and colleagues on discourses of climate delay as a framing device, to help us understand what’s happening here.

In her email column for Novara Media on Friday (not on the web, as far as I can see) Ash Sarkar picked up the same theme:

This latest salvo of climate dallying comes hot on the heels of a concerted push to diminish and deflect from the existential threat of global heating. In The Times, the bad Lawson sibling opined that fossil fuels aren’t going anywhere, nor should they if western powers want to compete with emerging economies...

It is, in part, due to the high tolerance of fools and bad-faith actors in the British media that such arguments can find purchase... While billionaires and corporations poison the atmosphere, the British media gets on with poisoning the airwaves.

In an article in Business Green that is in front of its paywall, editor James Murray reflects on what is happening here:

For much of the past five years, political opposition to the UK's climate policies has been surprisingly muted. The UK's world-leading net zero emission target was approved by Parliament with barely a whisper of dissent. ... it looked as if the plummeting cost of clean technologies, the sobering nature of escalating climate impacts, and the international pressure applied by both the Paris Agreement and fast-transforming energy and financial markets, meant the political consensus in support of a rapid net zero transition had become unimpeachable.

Murray characterises the arguments against the British government’s net zero strategy as being of three kinds.

The first is an insistence that they’re not disputing the science, or the desirability of getting to net zero sometime. The second is that while decarbonisation might therefore be a good thing, current policies will cost too much, and these costs will fall on less well off households. (When has the Daily Telegraph worried about less well off households?, I hear you thinking. Well, any straw person in a storm). The third is that whatever the UK does is a drop in the ocean because, China and India.

Murray does a good job of rebutting these arguments in his piece, so I’m not going to repeat his rebuttal here. But he is clear that all of this concern is so much disingenous tosh, to put it mildly:

if you really accept climate scientists' warnings but also think net zero strategies will fail then why is there no fear in your voice? You either don't understand the scale of the climate threat or you don't really believe it is a threat at all....

However, it is important to recognise that this campaign is a form of climate scepticism 2.0, because that realisation should inform the response from both the government and all those who want the net zero transition to accelerate. If you'll excuse the corporate speak cliché, the climate sceptic revival creates an urgent need for Ministers, green businesses, and climate hawk activists to lean in to the challenge ahead.

In the days when I was a journalist, I’d spend a few minutes each day scanning the right wing press to see what was exercising it. Weeks such as last week were rare, when opinion seemed orchestrated, and also quite a long way out of step. And although it is essential to take seriously any attempt to turn climate change into some adjunct to culture wars, I see the stridency, and the evidently bad faith arguments, as evidence that the global warning agenda is finally getting somewhere.

(Cartoon by Joel Pett for USA Today)

#2: Maybe the drone revolution isn’t

I’ve spent quite a lot of my professional time recently with people concerned about the humber of drones we might have in our skies in a decade or so, and the potential unmanageability that might come with that. And, to be honest, that seems to be the received wisdom about drones.

So it’s worth noting that Amazon, which is always mentioned in the same breath as the coming drone revolution, seems to be having second thoughts, with 100 employees losing their jobs at Amazon Prime Air.

The UK initiative was at the forefront of Amazon’s PR push to promote drones as the future of delivery a few years ago. It’s also worth noticing that Prime Air hasn’t managed a single test flight, if I’m reading the article correctly.

There seem to have been multiple problems here. One is the role of Amazon’s customer focus, which means that they specified a delivery that could more or less put the parcel on the doorstep This led to a requirement for larger drones that moved them into a different regulatory category. There were challenges in building the drones’ machine learning set. And the initial set of managers—who knew about drones—were apparently replaced by managers who know more about logistics, probably too early in the process.

In other words, the whole thing was just a lot more complex than Amazon expected:

Building such a system was a huge engineering and machine learning challenge. The systems required to make drones land outside people’s homes were heavy and Amazon’s drones ballooned to about 27 kilograms, according to Andreas Raptopoulos, CEO of drone company Matternet, which is heavier than the threshold used by some authorities to classify a small drone. Entering that higher weight category comes with a variety of extra regulations, including higher safety requirements to protect people on the ground from potential collisions. “The hard bit is the last two metres off the ground. It’s astonishing what machine learning can do, but it’s also astonishing what it gets wrong,” says professor Arthur Richards, head of aerial robotics at the Bristol Robotics Lab.

Some of the detail in the article also takes a bit of a shine off the reputation that Amazon normally has for managerial effectiveness:

Another source says their only contact with the central office was an American executive, who would visit every few months, buy the team pizza and then ask them to double their workload, without any explanation or answering any questions. “The best living metaphor for it all is that you had some bloke on the other side of the planet telling you what to do and then just leaving,” the source claims.

Andreas Raptopolous, quoted above, still thinks we’ll see commercial drone deliveries by the end of the decade. But it sounds like the delivery specifications will be simpler than Amazons.

H/t Exponential View

j2t#148

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.