15th July 2021. Social change | Technologies

Social change isn't speeding up: digital technologies are slowing down

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Social change isn’t speeding up

A group of academics has set out to work out whether social change is accelerating, or not. TL:DR? They conclude that it is not.

Since this isn’t what you hear from the hucksters on the conference circuit, it’s worth spending a little bit of time unpacking their analysis, which broadly unfolds in three parts.

It’s an open access journal, so the article isn’t behind a paywall.

Their starting point is a claim made a decade ago in the same journal, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, “that social change was proceeding at hyper-speed and, moreover, that it had consequently come to outpace technological change.“

They test this with US data, and with a narrow focus on social change.

The initial section reviews the literature, and spends some time trying to pull apart the technology literature, the economics literature, and the social change literature. This is a useful section that ranges from William Ogburn to the work of Emery and Trist:

This brief review suggests that while the social and the technological are deeply implicated in one another, it still makes sense to (a) keep the distinction between the two, and (b) develop an understanding of what social change might mean and how it might be measured.

The second section turns to data and discusses the challenges of measuring rates of change. Well, it’s complicated, of course. But eventually they decide to use US data (there’s lots of it) take a one hundred year time span, and draw on qualitative sources as well as quantitative. This data is organised into seven categories:

Population; Health; Home, Education & Leisure; Religion; Work; Wealth; Law & Order.

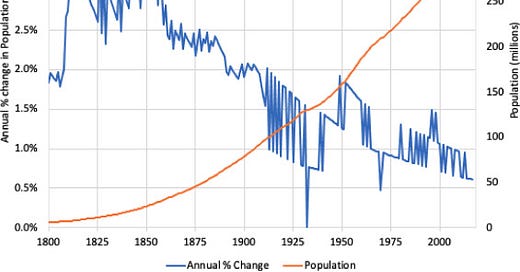

Pretty much all of these show more rapid growth in the first half of the century. Here’s the population chart, for example.

US population and Annual Percentage Change in Population

In fact, the only US indicators that seem to have accelerated rapidly since the 1970s is the incarceration rate.

From all of this they move to a conclusion, around five points.

The first is that answering the question raises lots of methodological problems, and epistemological ones.

The second is that every generation thinks that it is living through a period of change. But it needs more than this to assess whether social change is rapid.

Third, they underline that they have stayed away from technological change. Nonetheless, they nod in the direction of Robert Gordon, who concluded that the rate of technology change between 1860 and 1900 was much faster, and much more fundamental than that which we have experienced.

Fourth, they observe that none of the data they have looked at suggest that change happens in long waves.

If anything, the data would lean one towards a radical or punctuated equilibrium model of change, where a long period of relative stability is followed by an unexpected short period of rapid and revolutionary change.

They nod here to Peter Turchin’s structural-demographic model, but this also suggests that change is likely to occur around punctuated equilibria. And maybe using Google searches for the word ‘secession’ isn’t the best data point here.

Strauss and Howe suggest there’s an approximately 80-year model that runs from crisis to crisis, although their generational analysis within that is too tidy for its own good. In work I’ve done, there seems to be an approximately 40 year regulatory cycle, but this is driven more by an interaction between economics and politics than by social change.

Fifth, they point out that more research would be fruitful, and that there may be other ways of doing it:

A wealth of quantitative historical data is available for mining and analysis, and other indicators of social change may reveal a different picture, interesting patterns or intriguing relationships between constructs. To take but a few examples, we have paid no attention to phenomena such as the shifting prevalence of (illegal) drug consumption, hours of work, linguistic competence and preference, etc.

Their final question is about the discourse around rapid or accelerating social change:

Finally, it is worth asking why – and to whose benefit – there is so much talk of us living in a period of rapid and unprecedented change when perhaps the truth is that others have lived in more interesting and eventful times.

Who benefits? Salesmen and saleswomen of all stripes and types, I suspect. There’s nothing like talk of rapid change to create fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

H/t Ian Christie

#2: Digital technologies are slowing down

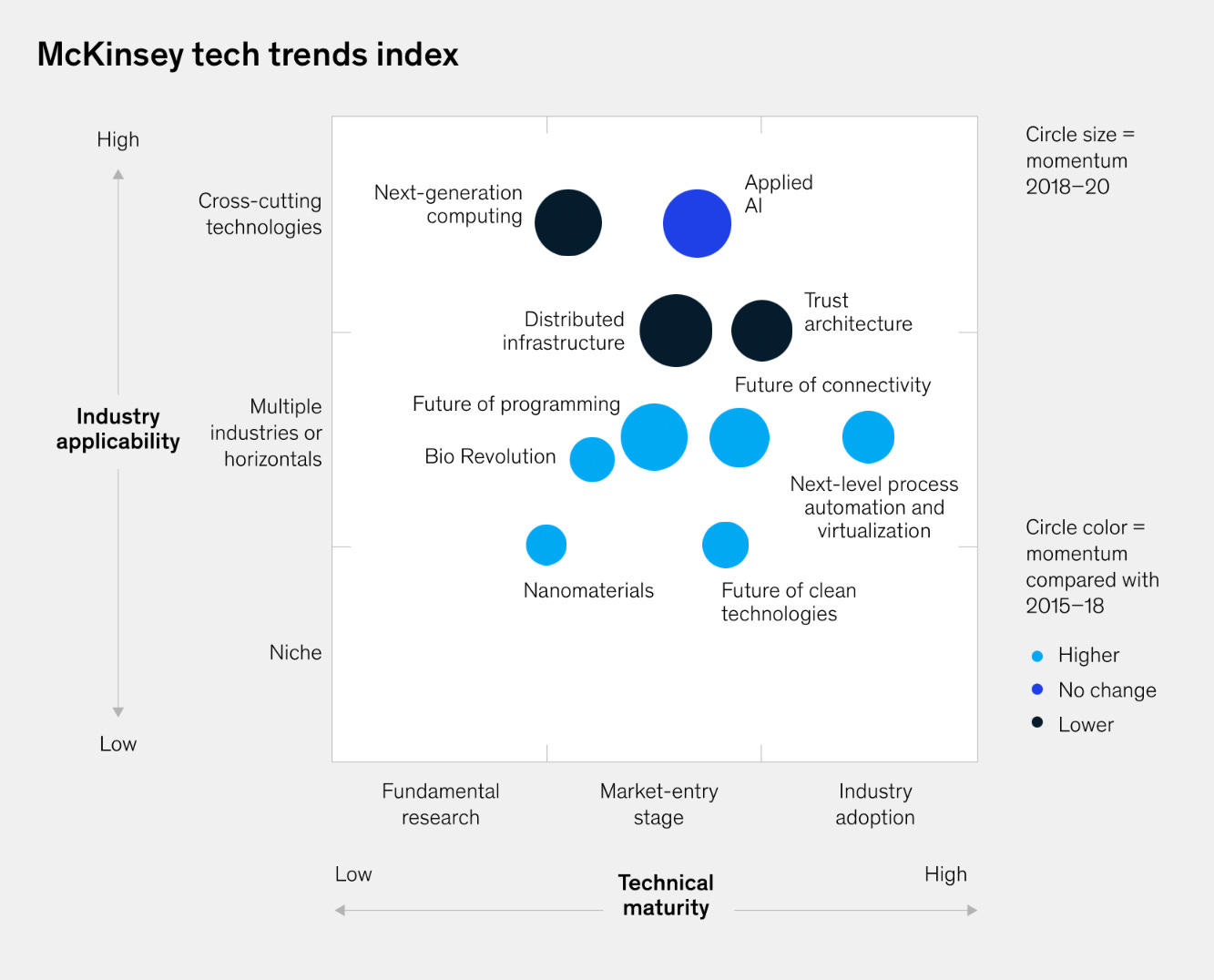

I haven’t the time to give this the analytical time it deserves, but there’s an interesting chart from McKinsey that shows their state of play on what they regard as key technologies.

Of course, some of these titles are a bit too vague to be useful: ‘bio revolution’? ‘Future of connectivity?’

But buried in here, in effect, is an S-curve model of current technologies. The colours indicate whether the technologies are slowing down (the sky blue ones are accelerating, so nearer the start of the S-curve, the dark blue static, the black ones slowing down, so nearer to the end).

I’m less persuaded by the vertical axis—whether or not a technology is “cross-cutting” as opposed to “multiple industries” might just be a feature of levels of maturity—but the horizontal access is an indication of technology readiness level, in effect.

As readers know, I like the Carlota Perez technology surge model, which suggests that the digital surge is in its late stages (although there’s likely quite a lot of social innovation still to come from digital).

My estimate is that the best candidates for the next surge—by which she means the dominant technologies and dominant idea of the time—are either a technology cluster around bio-technologies (driven by food, health, and ageing) or nano materials/clean technologies, driven by the requirements of re-engineering the planet for a post-carbon world.

So I’m not surprised to see both of these still towards the bottom left.

If you download the supporting document, best to ignore the breathless claims about technology, in general, speeding up. There’s quite a lot of contrary evidence. See the note on salesmen and saleswomen, above.

Update: I mentioned Iceland yesterday in my piece on the coming four day working wee. And right on cue, the FT has published an article about the Icelandic trial—which seems to be available outside of the paywall.

j2t#133

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.