Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Posts are currently less frequent while I’m away. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

This is a guest post by Peter Curry

The concept of using IQ to measure people’s intelligence has taken a pounding from progressives over the last thirty years, and perhaps deservedly so. It has been charged with perpetuating racism, with fostering inequality, and with giving a veneer of credence to the smug bastard society.

Generally, genetics tend to provoke aggression and discord from the left. The idea that your intelligence, or personality traits, or your tendency to get divorced can all be fixed from birth is an uncomfortable one.

The problem is that as genetics improves in accuracy, it also demands answers to difficult questions. Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioural geneticist, has spent time grappling with the complex issues that arise from evidence of genetic links with cognitive ability.

In 2003, researchers sequenced the entire human genome. Then we got genome-wide association studies, or GWAS. The quotes that follow are from a profile of Harden in The New Yorker:

Researchers then began to wonder if it might be possible to identify hundreds or even thousands of places in the genome where differences in our DNA sequences could be correlated with a trait or an outcome.

The largest GWAS for educational attainment to date found almost thirteen hundred sites on the genome that are correlated with success in school. Though each might have an infinitesimally small statistical relationship with the outcome, together they can be summed to produce a score that has predictive validity: those in the group with the highest scores were approximately five times more likely to graduate from college than those with the lowest scores—about as accurate a predictor as traditional social-science variables like parental income.

Charles Murray’s book The Bell Curve is infamous in this discussion, for its genetic explanation of racial differences. For many, the response was to deny the book altogether, and vilify any who tried to engage with it. Harden notes that you can’t simply say that it’s all wrong, because that would be intellectually dishonest.

Instead, she alludes to Jesus’ confrontation with Satan in the desert. You have to, as Jesus did, depict different portions as truthful and other parts as false.

There is a lot of good evidence, wrote Harden and Turkheimer in response to Murray, to support the ideas that “intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, is a meaningful construct” and that “individual differences in intelligence are moderately heritable.” They even conceded, with many qualifications, that “racial groups differ in their mean scores on IQ tests.”

But there was simply no good scientific reason to conclude that observed racial gaps were anything but the fallout from the effects of racism. They pointed out that in the one instance when Harris used James Flynn’s work to push back against Murray’s ideas, Murray responded with some hand-waving about a research paper that he admitted was too complicated for him to understand.

Here’s the rub. Currently liberal values make little allowance for discrimination based on any differences between peoples; skin colour, height, weight. And yet, there is a pernicious myth that continues to argue that intelligence is not among these quantities. There is an idea that if you’re willing to sweat and work hard and study, you can achieve anything.

Here’s Obama in 2012 espousing those values: “I believe we can keep the promise of our founders, the idea that if you’re willing to work hard… you can make it here in America if you’re willing to try.”

But as the science continues to show that intelligence is correlated with genes, the meritocratic message is exposed instead as a justification for those who have already made it to the top. This is a fine tightrope to walk, because it’s then possible to over-interpret this evidence the other way, and take a deterministic genetic approach:

In Blueprint, Robert Plomin wrote that polygenic scores should be understood as “fortune tellers” that can “foretell our futures from birth.” Jared Taylor, a white-supremacist leader, argued that Plomin’s book should ”destroy the basis for the entire egalitarian enterprise of the last 60 or so years.”

Fredrik deBoer, in his book The Cult of Smart, makes the argument that we should not discriminate on lines of intelligence. This feels to me like a naive argument, and Harden’s approach is instead to focus on using genetic studies to reduce inequity:

The perspective of “gene blindness,” she believes, “perpetuates the myth that those of us who have ‘succeeded’ in twenty-first century capitalism have done so primarily because of our own hard work and effort, and not because we happened to be the beneficiaries of accidents of birth—both environmental and genetic.”

There is a middle ground between ‘let’s never talk about genes and pretend cognitive ability doesn’t exist’ and ‘let’s just ask some questions that pander to a virulent on-line community populated by racists with swastikas in their Twitter bios.’

Peter Singer also weighs in:

Harden’s ethical arguments are ones that I have held for quite a long time. If you ignore these things that contribute to inequality, or pretend they don’t exist, you make it more difficult to achieve the kind of society that you value.

Harden herself argues on the lines of John Rawls and Elizabeth Anderson; that we need to reject “the idea that America is or could ever be the sort of ‘meritocracy’ where social goods are divided up according to what people deserve.”

Discussions of genetics and potential can give people anxiety. What if I am restricted by my genes? This is why the message of meritocracy is powerful - we don’t want to hear that we can’t do it. Genes do matter, but they’re only part of the story. Environments also matter, the people you talk to also matter, and your actions continue to matter.

#2: Why we need to be concerned about speed

It ought to be an obvious point, but speed is bad for the planet. Meaning that vehicles travelling at slower speeds have lower emissions. This is true for cars, for trains, for aeroplanes, for ships.

(Image: Autobahn Deutschland via Wikipedia)

The reason that this is suddenly visible as an issue—apart from the climate emergency—is that, as Bloomberg reports—the German Social Democrats have said that they will put a speed limit of 130km/h (81mph) on Germany’s autobahns if they become part of the next German government. The Greens would do the same thing. (Famously, Germany’s autobahns currently have no speed limit).

Even 81mph is probably too high: vehicle emissions start to climb when vehicle speeds go above 55mph, because of increasing air resistance.

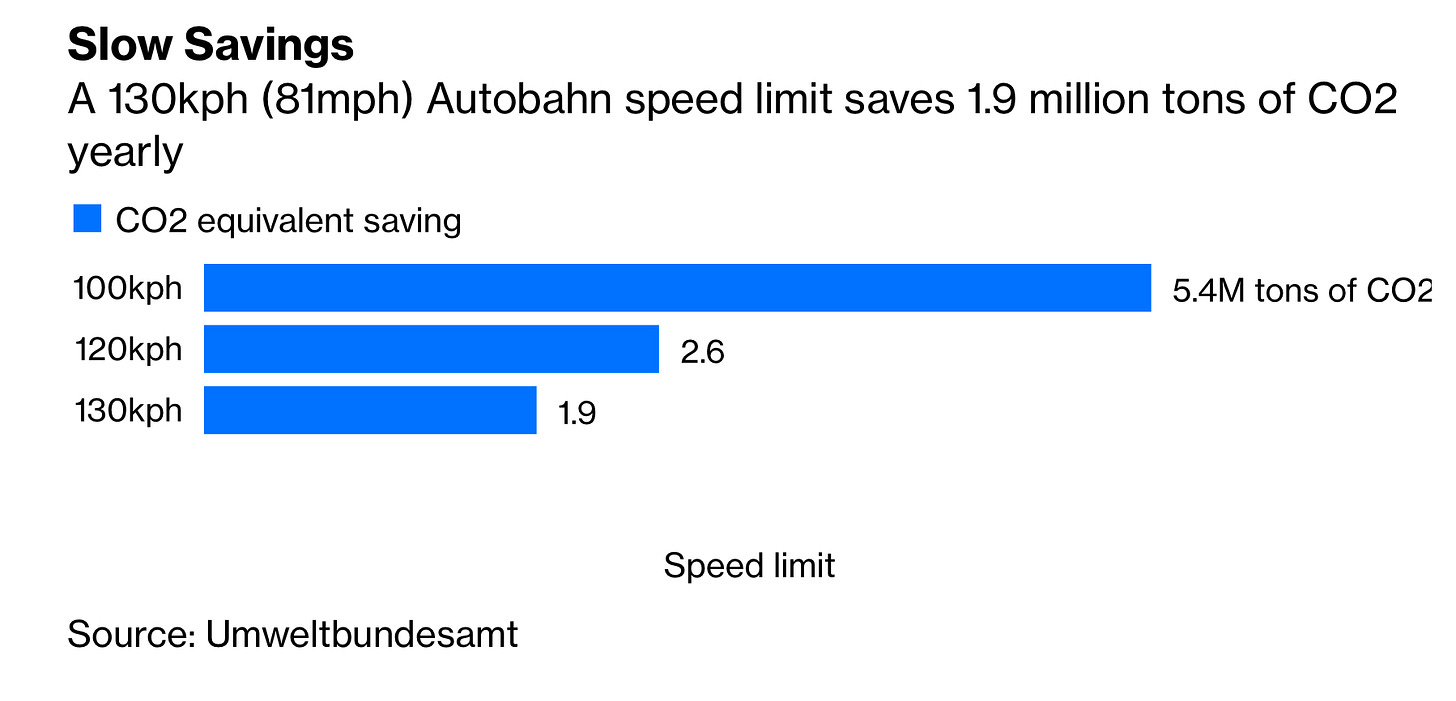

A 130 kph Autobann speed limit would lower greenhouse gas emissions by 1.9 million tons annually, according to the German Environment Agency. That’s barely 1% of Germany’s overall transport emissions, but nearly 5% of the total produced by cars and light commercial vehicles on highways, it estimates. A 120 kph speed limit would remove even more.

Presciently, the US imposed 55 mph speed limits on its freeways during the 1970s during the oil crisis. More recently the Netherlands has imposed 62mph limits on its motorways to reduce air pollution by cutting NOx emissions. Air pollution also means that this problem won’t vanish with electric vehicles. Half of vehicle-related air pollution comes from tyres and brake pads, and this also increases with higher speeds.

In the maritime sector, some freight operators have reduced emissions by steaming more slowly, although they’ve reached the limit of what they can do without switching to cleaner fuels.

This trend is only going in one direction. It’s the reason why supersonic planes are never going to be a starter (more here), and also why high speed rail will become slower as the climate emergency starts to bite.

j2t#167

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.