15 October 2021. Consumption | Memorials

Getting to sustainable consumption; remembering the COVID dead

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Getting to sustainable consumption

COP-26 is coming up fast, and we’re starting to see a steady drumbeat of reports and articles talking about what needs to be done—especially if we are to have a chance of staying within a (probably) livable increase of 1.5 degrees.

One of these reports is 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Towards A Fair Consumption Space for All by the Hot or Cool Institute and a whole lot of partners, including the Club of Rome and the Finnish innovation agency SITRA.

It’s a long report (just past 160 pages all-in) so I’ll just pick up a few points about the lifestyle adjustments that would be required for the richer citizens of the world to get to a fair consumption space for all. (Clue: despite the promises of the British Prime Minister, it doesn’t involve doing all the same things as we do now but using new technologies.)

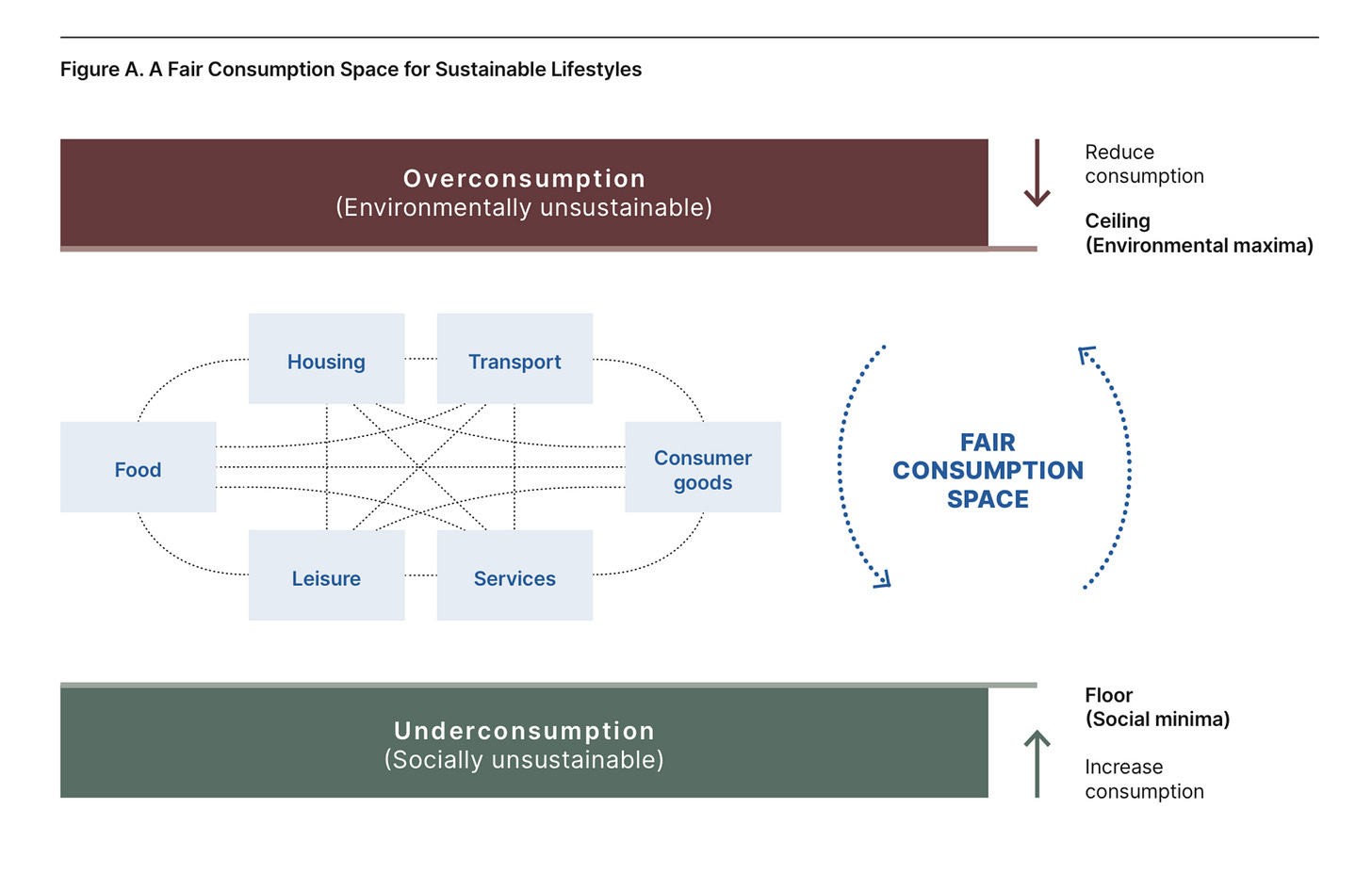

Their overall model of the “fair consumption space” seems to borrow from Kate Raworth’s doughnut: too much consumption, and we end up with economic harm. Too little, and we end up with social harm.

(Source: 1.5 degree lifestyles)

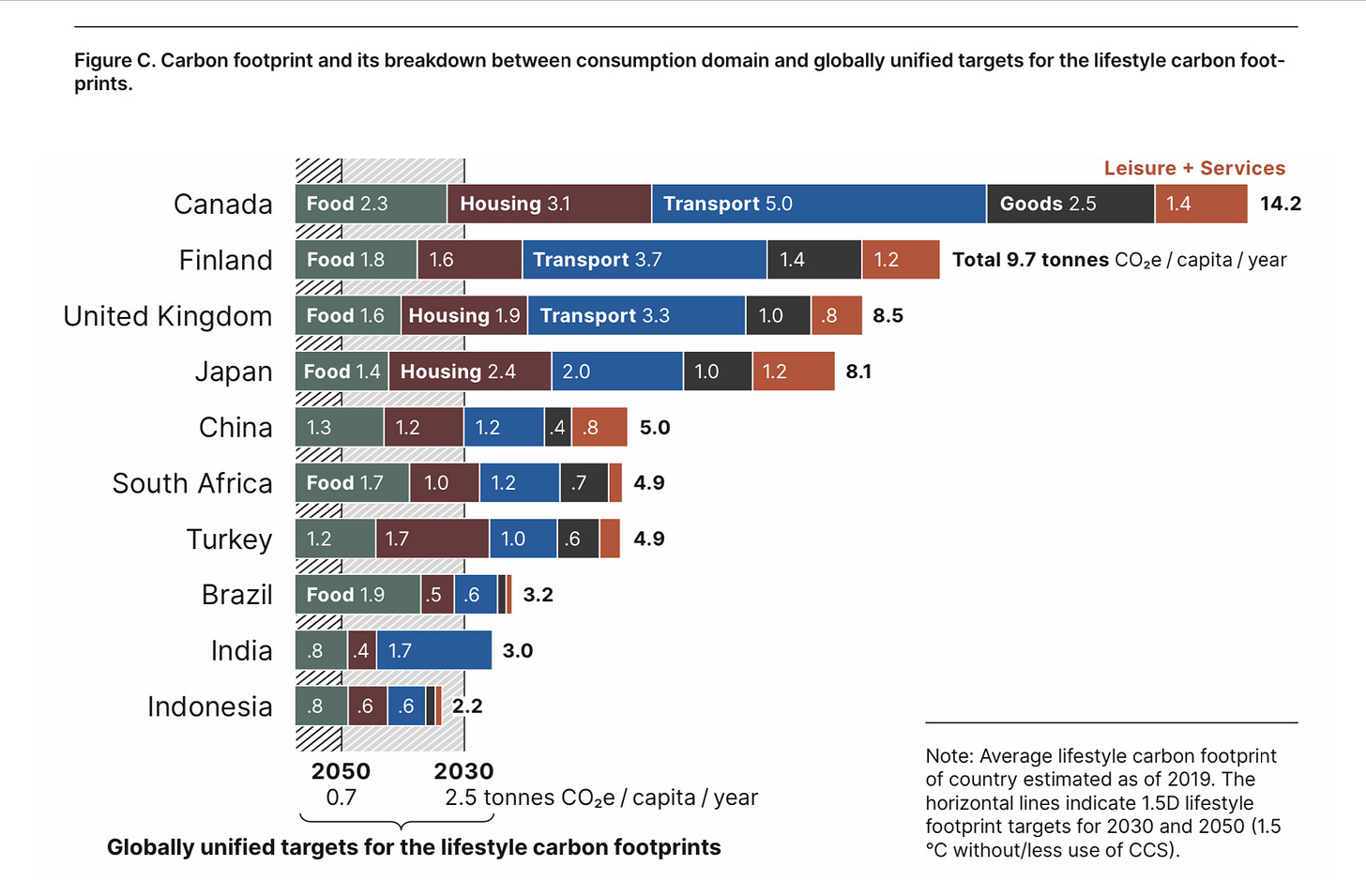

The report’s research looks at consumption in eight countries, from Canada to Indonesia, across five domains—food, transport, housing, goods, and leisure and services—and compares this current consumption to the amount we need to hit by 2030 and then by 2050. There’s a gap, almost everywhere.

(Source: 1.5 degree lifestyles)

Closing the gap? The executive summary suggests some priorities:

Practical solutions will require three parallel types of efforts: absolute reductions in high-impact consumption (such as flying and driving less); modal shifts towards more sustainable options (such as shifting from driving to public transport or biking); and efficiency improve- ments (such as shifting to electric cars), to use three ex- amples from the transportation realm.

The options with large emission reduction potentials as revealed in this report are reducing car travel, air travel, meat consumption, and fossil-based energy usage. If these options are fully implemented they could reduce the footprint of each domain by a few hundred kg to over a ton annually. The magnitude of impacts would depend on adoption rates of actions by the public.

There’s also a section with a concise summary of ten lessons from the research into enabling sustainable lifestyles.

1 Green consumption is not the same as sustainable living... In a sustainable lifestyles transition, we need to provide non-consumption and out-of-market options; and to protect lifestyles of communities already living well without consumerism.

2 The environmental impacts of lifestyles mainly come from four domains: food, personal transport, housing, and consumer goods.... Prioritising design, production, and consumption patterns in these domains will address about three-quarters of environmental impacts.

3 There is no universal sustainable lifestyle — what is sustainable in one place may not be sustainable in another. Successful examples of sustainable lifestyle practices should be replicated and scaled in new places only after careful adaptation.

4 The environmental impacts of lifestyles are not intentional but rather a consequence of people aspiring to fulfil needs or desires, and to function in society....Change needs to focus on the choice architecture (Szaszi et al. 2018), social values and norms, physical infrastructure, provisioning systems.

5 Increasing awareness does not necessarily lead to action.... Awareness is easily subordinated by lack of access or lock-in by prevailing options (Seto et al. 2016). In a sustainable society, the default options—the most widely available means of meeting needs—should already be made sustainable.

6 The question of individual behaviour change versus systems change is a false dichotomy....It is important to differentiate between the factors that can be addressed at the individual level and those that are beyond individual control, and to recognise how the two are mutually reinforcing.

7 Beyond the point of enabling basic needs and a life of dignity, having more money does not directly translate to more happiness. People’s expressions of happiness correlate with the level of trust in the community, social ties, education, health, and meaningful employment (Helliwell et al. 2020); and these tend to be less consumerist.

8 Inequality and perceived unfairness in society is a strong predictor of whether an intervention will fail or succeed. ... Ensuring sustainable lifestyles will fail if efforts are not made to address the extremes of pov- erty and wealth in society.

9 Lifestyles are not static; needs are a function of time and place.... Different stages of life bring different perspectives. Milestones and key transition moments in life—marriage, graduations, relocations, and births and deaths—offer heightened opportunities for reshaping lifestyles (Burningham and Venn 2017).

10 Sustainable lifestyles are not all about reducing consumption. A central tenet of sustainable societies is not complete abstinence but consump- tion within regenerative capacity (Wahl 2018). Social evolution includes examination and creative adaptation towards new ways of meeting our needs.

I think we know most of this already. The one glimmer of hope for me is in #7. I still read too many pieces that say that people in the rich world won’t give up buying stuff. But the things that make us feel better don’t involve consumption.

A point that’s also made in a chart in a recent blog post by Jeremy Lent.

(Credit: Kubiszewski et al., Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress)

His explanation:

When researchers developed a benchmark called the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), which incorporates qualitative components of well-being, they discovered a dramatic divergence between the two measures. GPI peaked in 1978 and has been steadily falling ever since, even while GDP continues to accelerate.

#2: Remembering the COVID dead

It’s closed now, but in the United States the artist Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg created a vast installation to commemorate the 695,000 Americans who have died of COVID-19.

It consisted of 695,000 small white flags, each one representing someone who has died of the virus, in 20 acres of space on the Mall near the Arlington Monument in Washington. A vast scoreboard updated the tally of deaths during the installation. People could send in messages about those died, which volunteers inscribed onto flags.

(Source: InAmerica.org)

On Twitter, there was a video of it. (You might have to click through to Twitter to see the video).

The art website Surface reported that the woek, called ‘In America: Remember’ is likely the largest participatory art installation on the Mall since the AIDS quilt.

The flags are arranged in 60-by-60-foot squares that create nearly four miles of paths within the busy stretch, which is often crowded by tourists. “I wanted to have enough pathways where people could wander the paths privately for their own quiet reflection,” says Firstenberg.

One tweet from a visitor captured the sound of the flags flapping in the wind (as above, click through to Twitter from the tweet if it’s nor displaying properly here).

j2t#188

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.