15 November 2023. Policing | Climate

Walking the floor at policing’s biggest tech event // Carbon emissions are a class problem // Food scenarios update [#515]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Walking the floor at policing’s biggest tech event

The Mark-Up’s weekly email is a good guide to technology issues, and last week’s email, by Ese Olumhense, reports on their recent visit to a big police show, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) conference in San Diego.

Massive respect to her for managing to connect it to a similar if fictional police conference that was the plot of an episode on Brooklyn 99. This was called Cop-Con, which is definitely a catchier title.

(IACP 2023. Source: theiacp.org.)

But that’s as far as the fun goes. Here are the three big themes in police technology at the moment, and none of this will surprise you:

Robotic tools like drones and police robots that could enter spaces that might be difficult or unsafe to send an officer. One drone I saw could come armed with a tool that allowed it to break a window.

Emerging and enhanced surveillance technologies like automatic license plate readers, which can capture images of cars and other vehicles that police officers can use to target investigative leads. In some cities, I learned, this kind of technology generates a million or more images a day.

Artificial intelligence and algorithmic products were, predictably, among the tools I saw the most. In addition to the voice analysis tools I described above, companies advertised tools that aggregate and analyze data (including social media, jail data systems, video feeds, court records, and social media) to generate quick insights.

As well as the email, there’s a longer article by Olumhense in The Markup in which she canvasses the opinions of technology experts on the tech that’s on show here. To give a sense of the scale of the event, there were 16,000 attendees, including police from “Indonesia, Ireland, the Dominican Republic, the United Kingdom, Brazil, the Ivory Coast, Kazakhstan, Haiti, Nigeria, the Bahamas, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Canada, and Jamaica”, and 700 companies were exhibiting.

Surveillance and privacy researchers were also there to note the trends and the discussions at the panel sessions. I’ll pick up a few of these here.

Drones were everywhere. There were multiple panels in which drones were positioned as “public safety ‘partners’” supporting police in situations that were awkward for humans:

One type of drone could be used with a mapping-and-scanning software that could build a three-dimensional model of a scene. Another could be used with an “arm” that could break windows and breach buildings.

Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who was also presenting at the event, watched a panel where the police chief of the Royal Bahamas logged into an online system and and then showed live video from an officer’s body camera on screen.

“We’d always said that body-worn cameras are just wearable surveillance; they’re turning police into surveillance networks,” Maass said. “And that’s something you can say rhetorically, but … quite literally they are hooking into a surveillance network so that police at headquarters can watch through body-worn cameras in real time. It’s just astounding.”

Other surveillance technologies, such as automated licence plated readers (ALPR) seem to be developing in concert with other related technologies:

“One of the things that I saw was a company selling an (automatic license plate recognition) camera that has gunshot detection in it,” said Gabriel Pereira , a researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science. “For example, if a car passes by that is very loud, that may be doing a race on the street or something like that, they allegedly could detect that with those ALPR cameras.”

But maybe one of the most interesting aspects of the event was a technology that seemed to be missing this year, according to Dave Maass:

“Up until this (year), face recognition was everywhere. I don’t think I saw one (vendor) on the floor that that was their main product they were pushing... I didn’t really see it brought up that often in panels. People just weren’t touching it. And I’m not sure that’s because the technology has become pretty toxic in public discourse, if it’s just not as useful and hasn’t lived up to promises — who knows, but people were not into it.”

(Day 1 of IACP 2023. Source: theiacp.org.)

There’s a famous cybernetics law called “the law of requisite variety”, coined by Ross Ashby, that says that organisations need to match the ‘variety’ in their external environment with their internal variety.

In a piece on The Edge in 2017, John Naughton explained Ashby’s Law:

if a system is to be able to deal successfully with the diversity of challenges that its environment produces, then it needs to have a repertoire of responses which is (at least) as nuanced as the problems thrown up by the environment. So a viable system is one that can handle the variability of its environment.

Ashby’s near-contemporary Stafford Beer would use policing as an example of ways in which organisations increased their variety—he was writing in the ‘70s, so was talking about the use of patrol cars and radios, and the kind of surveillance at the IACP’s ‘Cop-Con’ is clearly an extension of this.

But there are a couple of wider issues here. The first is that it allows governments to increase the ‘variety’ in the external policing environment by creating a whole new set of offences, largely in the public order, security, and “counter terrorism” area.

The other is that this has gone hand in hand with a plummeting decline in the level of public confidence in the police, certainly in the UK, and particularly in London. It’s possible that using technology to increase organisational ‘variety’ creates a perverse feedback loop that reduces trust and encourages more technology to be deployed.

Obviously we have no controlled experiments on this—1,600 delegates and 700 companies speaks to a gadarene rush—but the police might be better-off scaling back Robocop and getting closer to the street again. It’s possible to have the wrong kind of variety.

2: Carbon emissions are a class problem

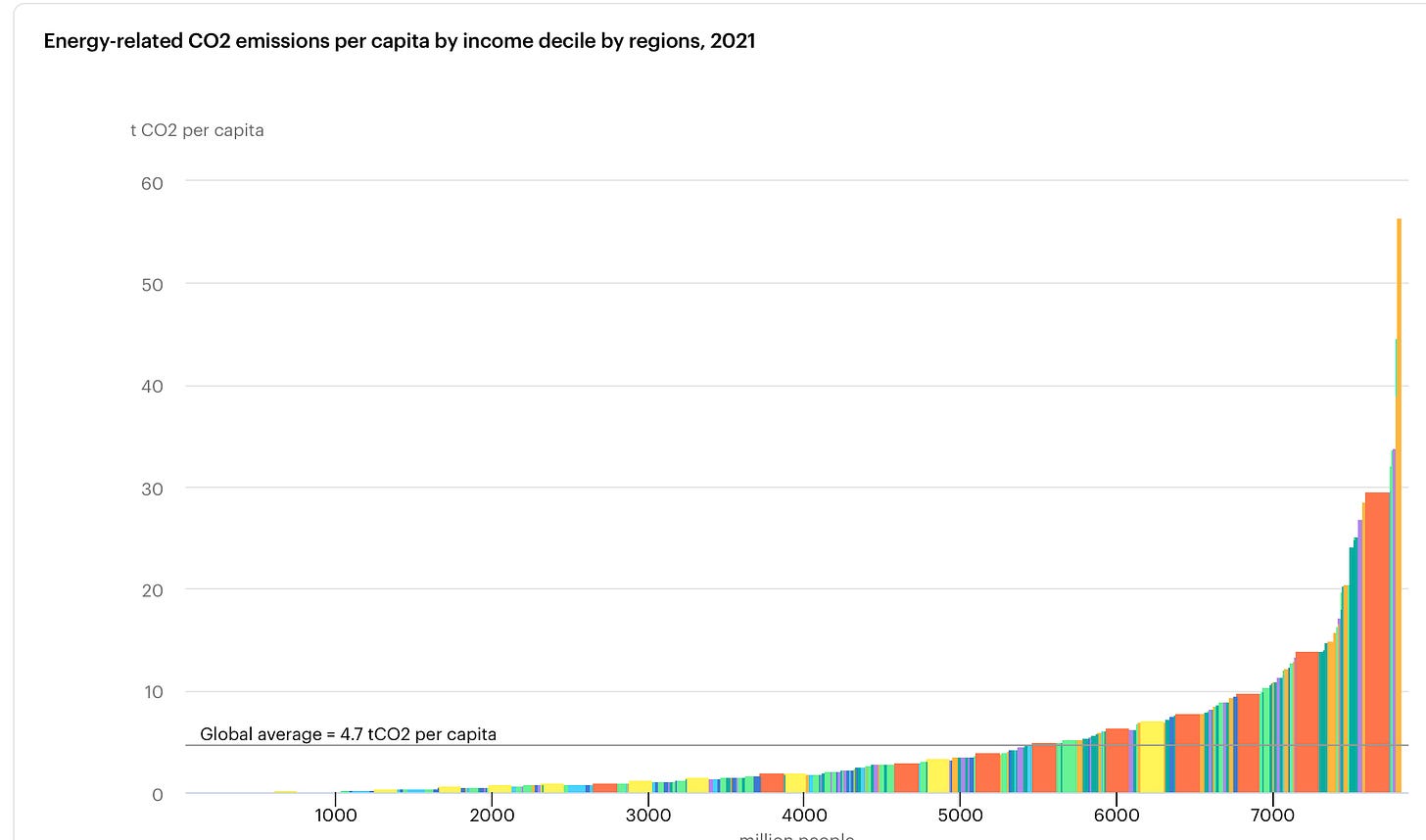

I’ve been meaning to share this piece about the share of emissions against share of incomes,, because is so stark and the charts show it so clearly. It’s from the IEA (the International Energy Agency) earlier this year and was headed ‘The world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1%’.

The piece looks at the difference in emissions by income—or class, perhaps, depending on the language you prefer. The average North American, it notes, produces 11 times as much emissions as the average African. But the economic differences, globally and within countries, as far starker:

The top 1% of emitters globally each had carbon footprints of over 50 tonnes of CO2 in 2021, more than 1 000 times greater than those of the bottom 1% of emitters. Meanwhile, the global average energy-related carbon footprint is around 4.7 tonnes of CO2 per person – the equivalent of taking two round-trip flights between Singapore and New York, or of driving an average SUV for 18 months.

The first chart, which is interactive in the original article, shows emissions by both region and decile. If you take out different regions, you see that they all follow the same emissions curve as you go up the income deciles from poorest tenth to richest tenth, from left to right. The only difference is that in some regions the absolute numbers are lower overall than in others.

(Key by region of the world. Source: IEA, 2023, CC BY 4.0)

And let’s just spell out some of the ratios and some of the numbers here:

Globally, the top 10% of emitters were responsible for almost half of global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021, compared with a mere 0.2% for the bottom 10%. The top 10% averaged 22 tonnes of CO2 per capita in 2021, over 200 times more than the average for the bottom 10%. There are 782 million people in the top 10% of emitters, extending well beyond traditional ideas of the super rich.

For comparison purposes, there are around 46 million millionaires or billionaires on the planet.

Although the top 10% of emitters are found on all continents, about 85% of them are in advanced economies,

including Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, United States, and United Kingdom – and also in China.

The rest are in Russia, the Middle East and South Africa, all places characterised by high levels of inequality and emissions-intensive energy systems.

The bottom 10% are all in Africa and Asia, with 0.2% of global emissions compared to 48% for the top 10%. Here’s the chart for that (downloadable here).

(Source: IEA, 2023, CC BY 4.0)

And here’s the data by decile for selected parts of the world: the USA, the EU, China, and India. The bottom decile is one the left, the top decile on the right.

(Source: IEA, 2023, CC BY 4.0)

There’s more on the US data, where the top 10% account for 40% of US emissions, in a recent piece at Yale 360.

Inside the top decile, the inequalities in wealth and emissions are even more stark:

As the Stockholm Environment Institute estimates , the richest 0.1% of the world’s population emitted 10 times more than all the rest of the richest 10% combined, exceeding a total footprint of 200 tonnes of CO2 per capita annually. Within this 0.1% are the billionaires and multimillionaires whose emissions-intensive super-yachts, private jets, and mansions have attracted the attention of climate activists.

Just to repeat that:

the richest 0.1% of the world’s population emitted 10 times more than all the rest of the richest 10% combined.

This is a big problem, but it also represent, maybe, an opportunity. The problem part is that if the top 10% carry on emitting at their current rate, they will use up the entire carbon budget that we have to stay within 1.5% by 2046.

On the other hand, being wealthier, they also have more scope, and more choice to reduce their emissions. The IEA team, possibly whistling in the dark to keep themselves cheerful, observe that they can represent the initial niche for an emerging low carbon market (as in the case of electric cars, for example.) And:

The investment choices of wealthy individuals also have a systemic impact on the development of clean energy solutions.

But given the levels of consumption disparities here, the impact on everyone else, and the apparently small impact of market signals on the emissions of the top 10%, it’s fairly clear that taxes or carbon pricing is unlikely to have an big enough effect quickly enough. Sooner or later, if we’re even half-serious about dealing with climate change (and I realise that richer economies may not even be half-serious), we’re going to have to regulate these behaviours.

Which is why initiatives like limits on frequent flying make sense, even if the idea of a levy probably won’t be enough on its own. Private jets will eventually end up in the regulatory crosshairs as well.

Update: food scenarios

It seems I jumped the gun a little in writing here about the scenarios about the future of food in a net zero world a couple of weeks ago. Publication was delayed slightly by the AFN Network while they made some design adjustments.

But the good news is that they have been published now. You can download the report from this page.

Thanks to Harry Rutter for spotting that it had been uploaded.

j2t#515

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.