15 July 2023. Innovation | Statistics

Electronic music and the imagination of the future // ‘Scoring high on all these measures’ [#478]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

I don’t have much time at the moment, so am falling back on the newsletter staple, and republishing in two parts (today and Tuesday) a piece I wrote for Compass, the newsletter of the Association of Professional Futurists, a few years ago. It’s about the emergence of electronic music into the mainstream, and includes a model of cultural change. And a playlist. Have a good weekend!

1: Electronic music and the imagination of the future

It’s cold outside.

The future arrives with a carapace of technology, but it is driven by culture. The idea of the future arrives long before the fact, made by people who are at odds with the present. And their future imagination, in turn, shapes the way the future turns out.

I’m going to explore this idea through several sources: a BBC documentary, Synth Britannia, about British electronic music in the ‘70s and 80s; the book Analog Days, on the history of the Moog synthesiser; and Simon Reynolds’ book on post-punk, Rip It Up and Start Again. Quotes in italics are from the documentary.

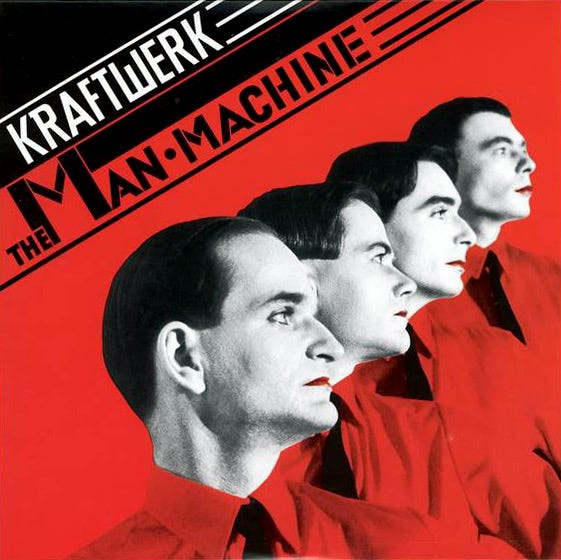

(Cover of Kraftwerk’s ‘Man Machine Music’. Designer: Karl Klefisch)

The futurist Graham Molitor teaches us that it takes 30-80 years for a weak policy signal to reach the policy mainstream, but in comparison electronic music travelled at the speed of sound. It is around 20 years from RCA’s first synthesiser in New York, and Robert Moog and Don Buchla playing around with kit in their respective workshops, to Britain’s first electro number one, by Tubeway Army. (There’s a playlist below).

Sitting behind this is a theory of cultural change, hugely simplified:

There are always small cracks in the dominant culture;

Sometimes, but not often, change is powerful enough to expand the cracks enough to break through, to "unfreeze" the dominant system;

When it does, the mainstream co-opts the change as quickly as possible (it is "dynamically conservative");

To do this it has to find ways to adapt to the new force of change (this is a complex adaptive system).

Or to put it slightly differently, systems and cultures are all but solid for much of the time, but open up at times of shock, soldifying again as a different but similar system. The story of this shock in the world of electronic music runs from A Clockwork Orange and German pioneers such as Kraftwerk, through the early British electronic groups such as Cabaret Voltaire, Heaven 17/Human League, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and Throbbing Gristle, to Gary Numan and Depeche Mode. But there’s also a literary connection as well, for these bands were influenced by Burroughs and J.G.Ballard, and sat in a moment of economic as well as cultural change.

CRACK

‘Mensch Machine/ Ein Wesen und ein Ding’

The story starts in the early ‘60s with the evolution of a number of competing competing electronic “synthesisers” (the name came later). The Moog was one; Don Buchla’s Buchla Box another. Like most new technologies, these early machines were cumbersome, expensive, and unreliable. They spent much of the decade in a complex dance with groups of interested users/customers (the distinction is always blurry in the early days of a technology), such as electronic composers and rock musicians, who were trying to understand what could be done with this emerging technology.

The Moog got noticed commercially in the late ‘60s through Walter (now Wendy) Carlos’ recordings of synthesised Bach, Switched-on Bach, which led to a commission to write the score for Stanley Kubrick’s version of A Clockwork Orange, based on the Anthony Burgess novel and set in a violent, indeterminate future.

If Wendy Carlos planted the seed, then the German band Kraftwerk was the catalyst for the explosion in electronic music, at least in the UK. They described themselves as “engineer-musicians,” and were trying to craft a music that neither looked across the Atlantic to the US, or back to Germany’s recent history. As Wolfgang Flür says on Synth Britannia,

“We had no long hair and we didn’t wear blue jeans. We had grey suits and short hair, and we looked like the children of Werner von Braun or Werner von Siemens.”

Both Kraftwerk’s form and technology caught the attention. Their 1974 song “Autobahn” ran for 22 minutes, a full side of an LP, with minimal lyrics that parodied the Beach Boys. The group’s first appearance on British television was not on a music show, but on the geek-science programme Tomorrow’s World in 1975.

A breathless reporter explains that they have eliminated non-electronic instruments from their line-up, and that the next step is to replace their keyboards with “jackets with electronic lapels which can be played by touch.”

The effect on Andy McCluskey of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, who saw Kraftwerk play in a half-empty venue in Liverpool, was immediate. Wolfgang Flür recalls that McCluskey came backstage after the concert:

“He said, ‘You know, guys, you have shown us the future. This is it. We throw away our guitars tomorrow, and buy all synthesisers.”

EXPAND

The handbrake penetrates your thigh/

Quick, let’s make love before you die.

The first Moogs were so expensive that only recording studios and rock stars could afford them; the Rolling Stones and George Harrison were early customers. The first uses by mainstream bands had been in the studio, as sources of sound design (for example on the Doors’ Strange Days), although more experimental synthesiser records such as Beaver & Krause’ Gandharva were also in circulation.

In the UK, the synth was associated with ‘prog-rock’ bands, in particular Emerson, Lake and Palmer; Keith Emerson became a star customer of Moog & Co, and his performances on it fitted fluently into the ‘70s rock narratives about stars and technical mastery. Even the MiniMoog, launched in 1970 as a synthesiser suitable for live performance still cost $1,195 (something over $7,000 at present prices).

(Image: Internet Archive)

By the late 1970s, punk had challenged the progressive rock sensibility. Even if the embryonic electronic community found punk music backward looking, punk was the shockwave that opened up the music industry, and the electronic community quickly picked up on its DIY attitude to open up a new aural space. On this reading, as Simon Reynolds argues in Rip It Up and Start Again, the most important singles of 1977 weren’t by the Clash or the Sex Pistols, but by Kraftwerk (‘Trans- Europe Express’) and Donna Summer (‘I Feel Love’):

"Moroder's electronic disco and Kraftwerk's serene synthpop conjured glistening visions of the Neu Europa - modern, forward-looking, and pristinely post-rock in the sense of having absolutely no debts to American music.P

As importantly, prices were falling; a small synth, such as the MiniKorg 700S, cost about the same as a good electric guitar. Martyn Ware, then of The Human League, later of Heaven 17, bought his instead of buying a second-hand car. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark got theirs through a catalogue, on weekly payments. Some saved money by building their own from kits: Chris Carter of Throbbing Gristle built his “Gristleisers” by following instructions in a copy of Practical Electronics.

Changes like this happen when societies are in liminal moments, "betwixt and between." The electronic music culture benefitted from two such transitions: the first in the 60s on the West Coast of the United States, where synthesisers fitted into the exploratory San Francisco “head” culture, and the second in Britain in the '70s. In the interviews in Synth Britannia, the musicians talk about their experience of watching Dr. Who, Blake’s Seven and the Quatermass films, and reading (in particular) the work of the British writer J.G.Ballard, especially his 1973 novel Crash. A city such as Sheffield, a location for groups such as Cabaret Voltaire, the Human League and Heaven 17, was on the cusp of industrial decline: London, which had already de-industrialised, had suffered significant depopulation. The times were extreme. As Simon Reynolds observes:

“The post punk era begins with the paralysis and stagnation of left-liberal politics, seen as fatally compromised and failed. and ends with monetarist economic policy in the ascendant, mass unemployment and widening social divisions. Especially in the early years, 1978-80, these dislocations produced a tremendous sense of dread and tension.”

John Foxx, working in London’s East End, speaks of producing music for the empty city.

“I wasn’t angry about it, in the way we’re supposed to be angry as punks. I just wanted to make music for it.”

Reynolds describes Foxx's song ‘Underpass’ as a “Ballardian idea”, the “dystopian spectral city.”

And Daniel Miller of The Normal wrote his single ‘Warm Leatherette’, later covered by Grace Jones, after reading Crash.

“It wasn’t like science fiction, it felt like it was five minutes into the future, and I loved that aspect of it, that it was so outrageous and so possible at the same time.”

These were classic experimental communities, working at the edges, aware of each other, in that moment of innovation where there is little distinction between producers and consumers. It is an unstable moment, in which either a new cultural market is created, or the community dissolves.

(In Part 2: it’s only a short step to Top of the Pops).

2: ‘Scoring high on all these measures’

You don’t see a poem about statistics for years and years, and then two slide across your screen in a single morning.

The first, by Peter Levine, is a response to a poem by the Polish Nobel Laureate Wisława Szymborska. The second, below, is a nicely-done pastiche of a famous T.S. Eliot cat poem by the sociologist Kieran Healey.

Statistics

Attentive to all in a conversation:

Ten percent of the population.

Someone's shame provokes a laugh:

Often true for over half.

Ready and willing to reconcile:

Rare below the top quintile.

Twenty percent, plus-or-minus three:

Those who’ll let an eccentric be.

Almost three out of every four

Are quick to pity the sick or poor,

But doing something to counter hate:

No more than one in any eight.

Scoring high on all these measures:

We've found no such human treasures.

Of compassion, pure examples?

One or two in all our samples.

But needing someone’s forgiving love:

Ninety-nine percent thereof.

(Peter Levine)

And the second, by Kieran Healey.

The Naming of Stats

The Naming of Stats is a difficult matter,

It isn’t just one of your holiday games;

You may think at first I’m as mad as a hatter

When I tell you, a stat must have THREE DIFFERENT NAMES.

First of all are the names where usage is informal,

Such as Median, Estimate, Average, or Range,

Such as Variance, Quartile, or else Standard Normal

All of them sensible everyday names.

There are fancier names that may be better-tasting,

Some for the frequentists, some for the Bayes:

Such as Skew, or Kurtosis, Metropolis–Hastings—

But all of them sensible everyday names.

But I tell you, a stat needs a name that’s obscurer,

A name that’s misleading, and hard to construe,

Else how can it keep on confusing the reader,

Or frustrate professors, or pass peer review?

Of names of this kind, there are many examples,

Like Hierarchical, Robust, or Omega-hat,

Such as Marginal, Confidence, or just Weighted Sample,

Names that always belong to more than one stat.

But above and beyond there’s still one name left over,

And that is the name that you never will guess;

The thing that no human research can discover—

But THE STAT MIGHT JUST KNOW, and be made to confess.

When you notice a stat getting quite widely cited,

The reason, I tell you, is always because:

Its user’s engaged, or enraged, or excited

At the prospect of pinning the root of all laws:

That inviolable, friable

Unidentifiable

Deep and inscrutable singular Cause.

(Kieran Healey)

My thanks to Ian Christie for the Peter Levine link, and to John Naughton, indirectly, for the Kieran Healey link.

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.