15 March 2022. Democracy | Art

Autocracy is on the rise. We knew that, but here’s the data. Surrealism—from Paris to the world.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Autocracy is on the rise. Here’s the data

The V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg produces one of the largest analyses of the state of democracy—an annual assessment based on a huge dataset and engagement with 3,700 experts. (The dataset is here). The report on 2021 is just out, and makes depressing reading, at least for democrats.

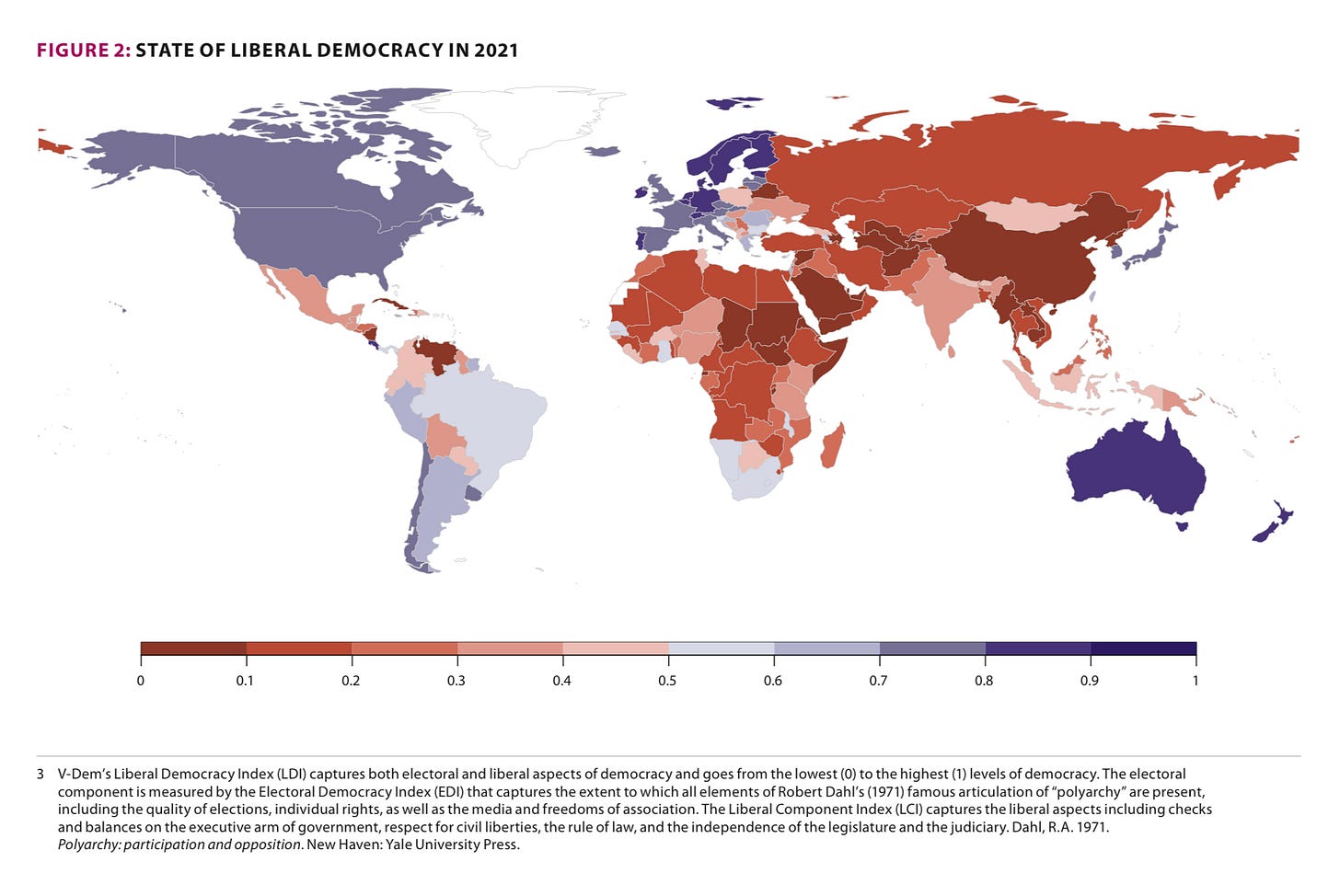

In summary, over the course of the last decade (2011-21), the share of the world’s population living in autocracies has increased from 49% to 70%; the number of countries threatening freedom of expression has increased from five to 35; and the number of countries where “toxic polarisation” is increasing—it “captures declining respect for legitimate opposition, pluralism, and counterarguments measured by the deliberative component”—has increased from five to 32.

Taking a longer view, the level of democracy globally has now dropped to the levels it was at in 1989.

They also suggest that the nature of autocracy is changing—more on that lower down.

(Source: V-Dem)

The report was finished on 24th February, the day that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and this isn’t lost on the authors:

For years, scholars warned that the global wave of autocratization would lead to more wars, both inter-state and civil.

In general, 2021 was not a good year for democracies. There were five military coups and one ‘self-coup’ (in Tunisia):

These coups contributed to driving the uptick in the number of closed autocracies. They also seem to signal a shift toward emboldened actors, given the previous decline in coups during the 21st century. Polarization and government misinformation are also increasing. These trends are interconnected. Polarized publics are more likely to demonize political opponents and distrust information from diverse sources, and mobilization shifts as a result. The increase in misinformation and polarization further signals what may prove to be a changing nature of autocratization in the world today.

—

(Source: V-Dem)

The V-Dem framework classifies countries into four types—two types of democracies and two types of autocracies:

The Regimes of the World measure is a categorical measure classifying countries into four distinct regimes: the two forms of democracy (electoral and liberal) and two types of autocracies (electoral and closed). To be considered minimally democratic, i.e. an electoral democracy, a country has to meet sufficiently high levels of free and fair elections as well as universal suffrage, freedom of expression and association. Hence, solely holding elections does not suffice for a country to be considered democratic.... In electoral autocracies, there are institutions emulating democracy but falling substantially below the threshold for democracy in terms of authenticity or quality.

The researchers says that in 2021 15 countries are democratising, but 33 are autocratizing. But the countries that are autocratizing are far more populous than the democratisers—they include Brazil, Hungary, India, Poland, Serbia, and Turkey—so represent 36% of the world’s population against 3%. One alarm signal for the EU is that according to the V-Dem data six of its 27 members are autocratizing: Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Croatia, Czech Republic and Greece.

Of course, at the edges of these four categories there are countries heading in both directions in any given year.

Two countries – Armenia and Bolivia – made democratic transitions from electoral autocracy to electoral democracy in 2021. But four countries were also downgraded over the last year from liberal democracy to electoral democracy: Austria, Ghana, Portugal, and Trinidad and Tobago. For Austria, a significant decline on the indicator for transparent laws and predictable enforcement is a decisive change that contributed to Austria falling below the criteria for liberal democracy.

—

(Source: V-Dem)

The researchers say that there are three aspects to their perception that the nature of autocracy is changing.

The first is that it may be more abrupt—as evidenced by the six coups they document. (Of course, this may be a blip rather than a trend; the nature of these kinds of data is that they may reflect a set of particular outcomes in particular countries.)

The second is that “toxic polarisation” is increasing in more countries—40 worldwide—and polarisation and autocratization create a reinforcing cycle:

Polarization becomes toxic when it reaches extreme levels. Camps of “Us vs. Them” start questioning the moral legitimacy of each other and start treating opposition as an existential threat to a way of life or a nation... Once political elites and their followers no longer believe that political opponents are legitimate and deserve equal respect, democratic norms and rules can be set aside to “save the nation”.

And this relates to the third point: governments are increasingly using misinformation

as a tool to manipulate public opinion and their inter- national reputations. Government manipulation of statistics and surging misinformation in digital media also show how political leaders are becoming bolder in furthering autocratization.

There’s a mass of detail in the report, both in terms of data and detail at the national level. There’s a section, for example, on the US and the 6th January insurgency:

The events on January 6th did not affect the U.S. LDI score. However, liberal democracy remains significantly lower than before Trump came to power. Government misinformation declined last year but did not return to previous levels. Toxic levels of polarization continue to increase. Democracy survives in the United States, but it remains under threat.

There’s also a well-referenced section making the case for democracy. They are better for economic development, education, peace and human security, global health, sustainable environmental and climate change mitigation, gender outcomes, public goods, and reducing corruption. They propose, in a ‘Concept Note’, an International Scientific Panel on Democracy (ISPD) to propose “scientific guidance on democratic resilience and protection”.

One left field thought I had when reading it was about the response by Europe and the US to the invasion of Ukraine—which surprised sympathetic observers as much as it seems to have surprised Putin. I thought it might be because of this sense, in the report, that democracies need to take a stand somewhere if they are to survive.

2: From Paris to the world

I haven’t been able to visit it yet, but there’s a big exhibition on surrealism on at the Tate Modern in London at the moment, and through the summer. It has transferred from the New York Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art. It’s reviewed by Morgan Falconer in Apollo Magazine.

I’ll keep this short, since the piece above is on the long side.

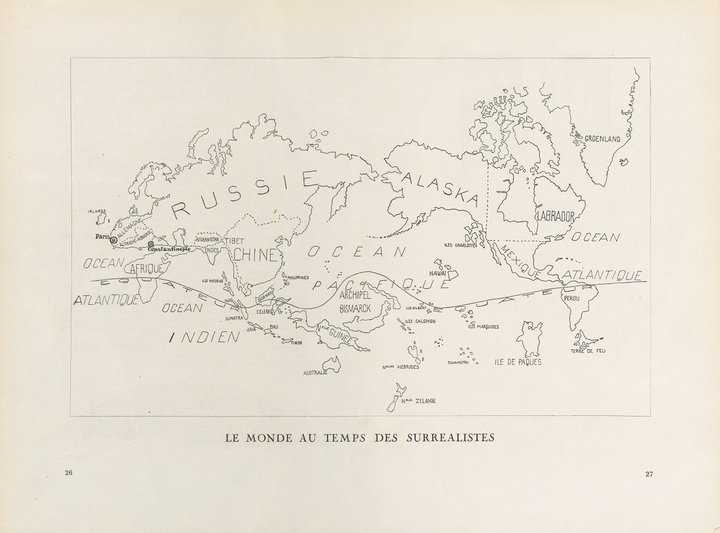

"Le monde au temps des surréalistes” (The World in the Time of the Surrealists), from Variétés (Brussels), special Surrealist number, June 1929 Tate Library. (Source: Tate Modern)

The theme of the exhibition is of surrealism as an international movement—not exactly decolonising it, but a sniff in that direction. Its founder, Andre Breton, certainly had international ambitions for the movement even if, as it were, they always had Paris:

With efforts afoot to bring more diverse and global perspectives to Western art history, Surrealism is a sound place to start, not merely due to Breton’s wanderlust but because he increasingly branded the movement as a global concern. He published an ‘International Bulletin of Surrealism’ and organised a slew of wide-ranging surveys in cities from Mexico City to Prague, Copenhagen and, again and again, Paris. The goal of ‘Surrealism Beyond Borders’... is to release the persistent grip of Paris on our imaginations and take in the world.

Part of its internationalism, Falconer suggests, was down to the fact that much of surrealism was a form of introspection, and although he doesn’t quite say this in the review, well, you can be introspective anywhere. Some of the later manifestations—such as in Czechoslovakia, where surrealism meets communism—seem intriguing. And certainly a number of the surrealists were both anti-colonial and interested in ethnographic art:

The most notable exhibit to address this is a finial from a slit gong made by people from Vanuatu, which was exhibited in one of the group’s typically internationalising shows in New York in 1960, ‘Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain’. Of course, works like this were simply ciphers on to which Surrealists projected whatever notions entertained them – notions no more accurate than those of hungry colonisers.

Of course, art movements never quite escape the moment of their birth. Surrealism captured the imagination because, at the time, we were captured by ideas of the imagination and the unconscious. And, of course, it became rampagingly fashionable:

(T)he style spread because it became the hippest, most cosmopolitan language of modern alienation. It could be accessible, easily generated, sometimes spooky or titillating, and chic collectors were gently scandalised by it. ... When Louis Aragon was rhapsodising the uncanny in the Paris Arcades and Max Ernst was painting petrified cities, you couldn’t want anything more. But all good things come to an end.

j2t#279

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.