14 June 2023. Energy | Politics [2]

Getting to a fossil-fuel free Britain by 2050 is possible // The narcissistic politics that drives populism may be on the slide. (#466)

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Getting to a fossil-free energy system

An interesting report from three University College London researchers (pdf) argues that Britain could pretty much be fossil-energy free by 2045–and will have stopped importing fossil fuels before that.

The report is based on three modelling scenarios in which the scale of ambition in addressing the sources of fossil fuel demand is ratcheted a bit higher in each version. So part of the interesting bit was looking at the places where there is significant levels of energy demand in the UK, and what can be done to reduce related oil and gas demand in each of these.

(NWT Cley Marshes, Norfolk: a heat pump pioneer. Photo by Pauline E/ Geograph. CC BY-SA 2.0)

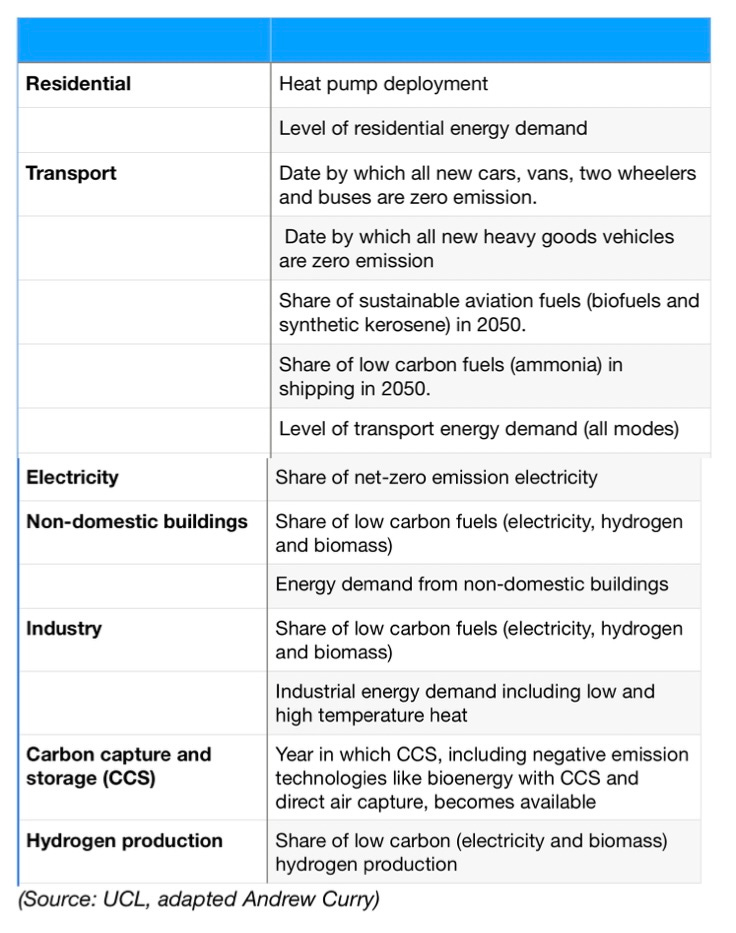

Quite early on they spell out the sources of oil and gas demand in the current system, and then look at ‘levers’ that could reduce this demand. So, oil first:

(O)il, in the form of petroleum products, is predominantly consumed by road and air transport and non-energy use, i.e. as a feedstock into the petrochemical industry, with smaller amounts used in shipping, buildings, industry and agriculture.

Natural gas, in contrast, is almost entirely used in buildings,

used mainly for heating from gas boilers, electricity generation and industry.

There’s a helpful chart which tries to show the breakdown of all of this, but the colour coding isn’t the clearest in the world, since there are 12 categories in it.

No matter. The main ‘levers’ to reduce this are as follows:

For clarity, I have simplified this slightly, since some of the things described as ‘levers’ in the report are just modelling references, such as ‘Heat pump roll-out rate in 2028’.

And this list doesn’t cover all sources of energy demand, but it certainly covers the most important ones—transport, buildings, electricity, industry, and so on.

The ‘scenarios’ are a set of pathways rather than scenarios—‘Emerging’ is less ambitious than ‘Developing’, and ‘Developing’ is less ambitious than ‘Secure’. In setting their numbers—some of which do look ambitious, especially in the ‘Secure’ pathway—they have drawn on a range of mainstream sources,

including UK government targets, the academic literature, and our existing academic network as well as existing energy scenarios from the Climate Change Committee (CCC) and the National Grid (NG). Taken together, these serve as a benchmark to shape our selections.

The ‘Emerging’ scenario is described as a reference scenario, based on government policy, so it includes

the current targets of 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2028 and the phase out of the sale of new ICE cars and vans by 2035.

'Developing’ borrows more heavily on the Climate Change Commission’s Balanced Net-zero Pathway. ‘Secure’ stretches these targets, but not by much.

I mentioned on Monday the speed of the change of the policy response in Europe in response to the Ukraine war, and in particular how Europe had swivelled its energy policy to remove demand from Russian gas. The authors reference some specifics of policy change in Europe around energy consumption:

For space heating, the EU’s REPowerEU policy package... has seen a 38% increase in heat pump installation from 2021 to 20228. Italy leads the way with nearly 500,000 heat pumps sold in 2022 (following a 37% growth from 2021) with other populous countries like France and Germany seeing around 300,000 (up 30% from 2021) and 275,000 (up 58% from 2021) installations, respectively. The UK is lagging behind these other countries with around 60,000 heat pumps sold in 2022. Similar growth to that seen in the other nations could yet see the UK reaching or exceeding its 2028 Government target of 600,000 installations per year, provided the necessary policy support is forthcoming to sustain it.

And on the transition in the vehicle fleet to electric:

Electric car penetration is another noteworthy comparator, with the European leader Norway seeing 79% of new car sales in 2022 being full battery electric compared with the UK recording a 16.6% share... (I)t is useful to observe that it has taken Norway around 7 years to increase the share of new cars which are battery electric from roughly today’s UK level to its present figure.

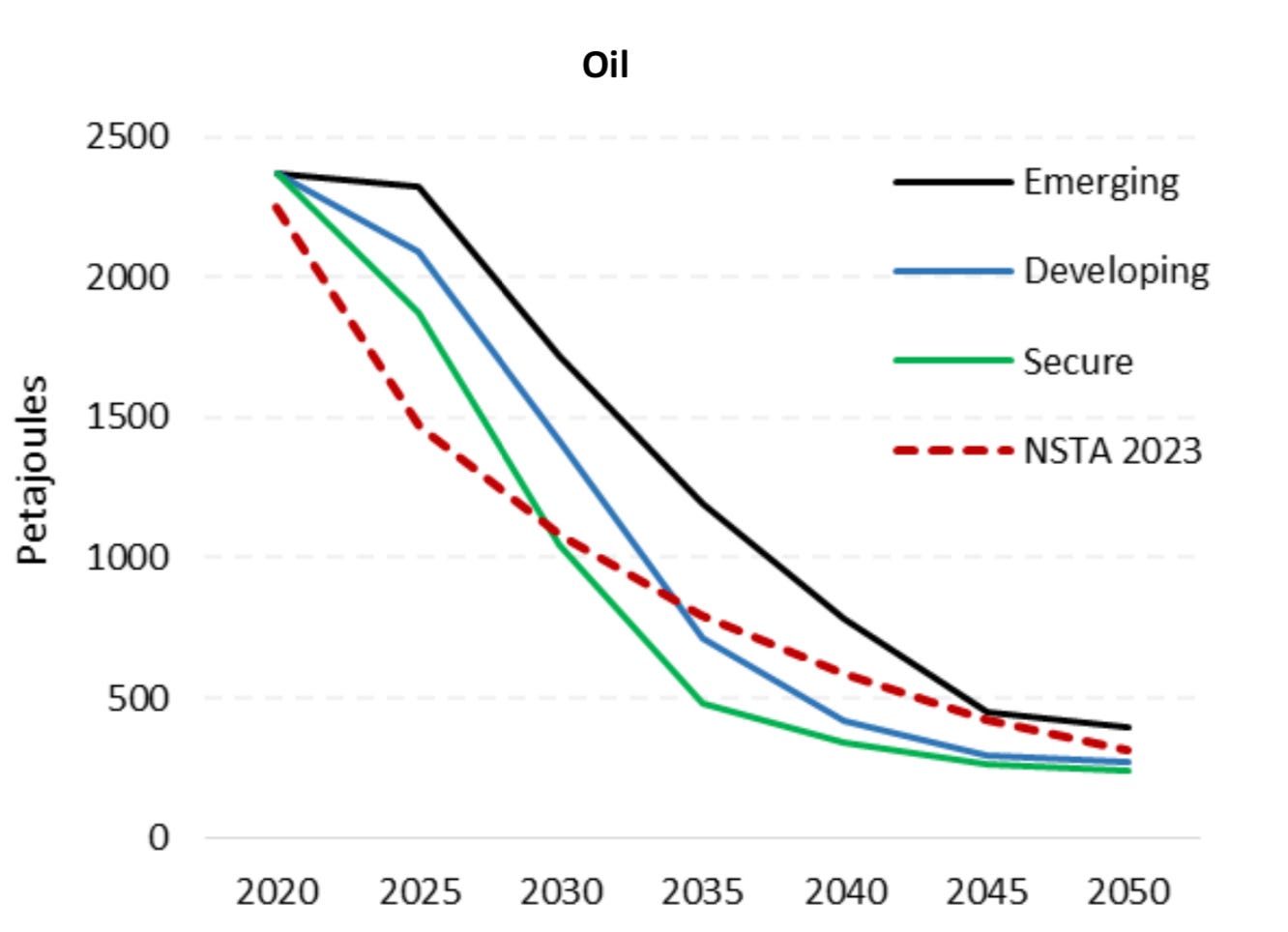

Under the different scenarios, the different scenarios look like this, oil first, then natural gas. The red dotted line is the projection of declining oil and gas production from the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA).

(Oil (top panel) and natural gas (bottom panel) demand from the UK energy system in our scenarios compared with NSTA projections of production updated in February 2023).

It’s not a long report, but there is quite a lot of detail in it. Their own assessment of the implications are that:

If Developing or Secure were implemented in full, then the UK would be pretty much free of oil demand in terms of energy by 2045.

Depending on which of these two scenarios it implemented, it could end natural gas demand between 2045 and 2050.

There’s a period before all of these dates where the only fossil fuels that the UK is consuming are coming from the North Sea, which obviously is good in terms of UK energy security.

But it’s also worth noting the relatively large gap in terms of fossil fuel use between the different scenarios, given that the climate change numbers require us to reduce fossil fuel use earlier rather than later.

There’s an interesting insight in the detail—that so called ‘blue hydrogen’, which uses natural gas as a feedstock, could come and go as an industry in something like a decade, which suggests that it would be better to start with ‘green’ hydrogen, from renewables, from the start.

A couple of observations from me. The first is that achieving the numbers in these scenarios requires a government that has both a climate strategy and an industrial strategy. This is one of the reasons (apart from the underlying economic illiteracy) that it is so disappointing to see the British Labour Party wibbling about fiscal rules rather than committing to investing in the green transition.

This is one of the significant differences between the EU and the UK at the moment.

The other is that part of this climate/industrial strategy needs a significant commitment to increasing investment in skills—which overall the British economy needs quite badly as well. But that’s the other significant difference here between the EU and the UK. Britain is poor at building skills, as the National Audit Office pointed out last year:

the skills challenge that government is facing has grown significantly, with key indicators going in the wrong direction. Employers’ investment in workforce training has declined, as have participation in government-funded skills programmes and the programmes’ impact on productivity.

2: The narcissistic politics of populism

On Monday, I wrote about the contemporary phenomenon of politicians, and other leaders, who were narcissists. That first post included definitions of narcissism. But this extends beyond leaders into politics more generally.

(‘Narcissus’, by Caravaggio. Circa 1594-96. Rijksmuseum. Public domain)

A 2020 study by in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletinfound that people with narcissistic personality traits were more likely to to be involved in politics. The study was conducted by Pete Hatemi and Zoltan Fasekas, and was based on existing survey data from the United States and Denmark:

(T)he surveys assessed narcissism and eight types of political participation: signing a petition, boycotting or buying products for political reasons, participating in a demonstration, attending political meetings, contacting politicians, donating money, contacting the media, and taking part in political forums and discussion groups.

In general there was little difference between non-narcissists and narcissists when it came to voting, but for all of the rest of political activity, narcissists were more involved. They are more likely to contact politicians, to sign petitions, to donate money, and, in the US, to vote in the slightly lower profile mid-term elections.

“The general picture is that individuals who believe in themselves, and believe that they are better than others, engage in the political process more,” the researchers wrote in their study. “At the same time, those individuals who are more self-sufficient are also less likely to take part in the political process. This means that policies and electoral outcomes could increasingly be guided by those who both want more, but give less.”

In an interview, Hatemi also noted the role of social media in amplifying certain types of behaviour:

“It is hard not to notice how much more of ‘me’ is part of our world — projecting one’s status at the cost of others, whether using social media such as Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. Gone are the days when children’s goals were to be something or do something important, replaced by the desire to be famous.

(‘Narcissus and Echo’, by David Revoy. 2006. CC BY 4.0)

It gets a bit worse than this. In terms of politics, people with a more narcissistic self-view are less likely to support the idea of democracy. (There’s only a summary of this research in front of the journal paywall). Researchers at the University of Kent and the Polish Academy of Sciences (in a 2018 paper) built on previous research that found that basic personality traits could predict individual opinions about the social world. Their research was in Poland and the United States. The summary describes the rationale in this way:

(T)his is probably because narcissists tend to feel entitled and superior to others, which results in lower tolerance of diverse political opinions. In contrast, people who take a positive, non-defensive self-view and trust others are more likely to show support for democracy, the research found.

This seems to link to a 2019 paper in in Political Psychology. by Polish researchers in Poland and London, on the idea of “collective narcissism”. From the abstract, collective narcissism is

the belief that the ingroup's exceptionality is not sufficiently appreciated by others. Collective narcissism is motivated by the investment of an undermined sense of self-esteem into the belief in the ingroup's entitlement to privilege. Collective narcissism lies in the heart of populist rhetoric. The belief in ingroup's exceptionality compensates the undermined sense of self-worth, leaving collective narcissists hypervigilant to signs of threat to the ingroup's position. People endorsing the collective narcissistic belief are prone to biased perceptions of intergroup situations and to conspiratorial thinking. They retaliate to imagined provocations against the ingroup but sometimes overlook real threats. They are prejudiced and hostile.

The thing of this, of course, is that the notion that one’s sense of self-worth is being undermined might not just be a pathology. It can also be a product of the material conditions that you find yourself in. Sometimes, the cat has actually pissed on the couch.

The combination of globalisation and technology, and the politics and economics of how these were managed, spread out a lot of losers while also funnelling the gains into a smaller number of winners. Equally, the political economy of the ‘Third Way’, and other convenient political fictions, emphasised the market in the provision of public goods such as health and education. As Marianne Fotaki wrote in a prescient (2014) piece on the LSE blog:

Susan Long has persuasively argued that whole societies may be caught in a state of pathological perversion whenever instrumentality overrides relationality – that is, whenever narcissism becomes dominant, other people (or the whole groups of other people) are seen not as others, like oneself, but as objects to be used. For instance, when markets are seen as anonymous ‘virtual’ structures, employees may be seen and treated as exploitable commodities. Such behaviours are pathologically perverse in that people disavow their knowledge of the situations they create through narcissistic processes.

We can take this further, I think. The role of businesses and business leaders in sponsoring narcissistic leaders and supporting policies that increased the transactional nature of society and of work has amplified the sense of drift and lack of esteem felt by individuals in societies.

Academics being academics, most of these researchers don’t offer prognoses of what might happen next. When they do, they are pessimistic. But it is certainly possible to speculate that some of the trends that made possible the politics of narcissism are in retreat.

One of the effects of the populist crisis has been to make politicians more aware of the losers from globalisation, even if they still sometimes seem to find it hard to do that much about it. Facebook, certainly, is in something of a decline, as its user base ages.

Some of the values of Millennials seem quite individualist to me (though less so than Boomers and GenX), and in workplace settings they are less likely to put up with the behaviours of narcissistic leaders. GenZ seems more interested in self-esteem and less in narcissism, which is one of the things I took away from John Higgs’ book The Future Starts Here. His take on the GenZ worldview:

It is only when everyone accepts how everyone else defines themselves that the world can be trusted to allow you to be yourself.

All the same, certainly in the US, the politics of grievance both going strong and is actively fuelled by the Republican Party. And Vladimir Putin, of course, shows every sign of grandiose narcissism without any checks or balances, at least this side of the International Criminal Court.

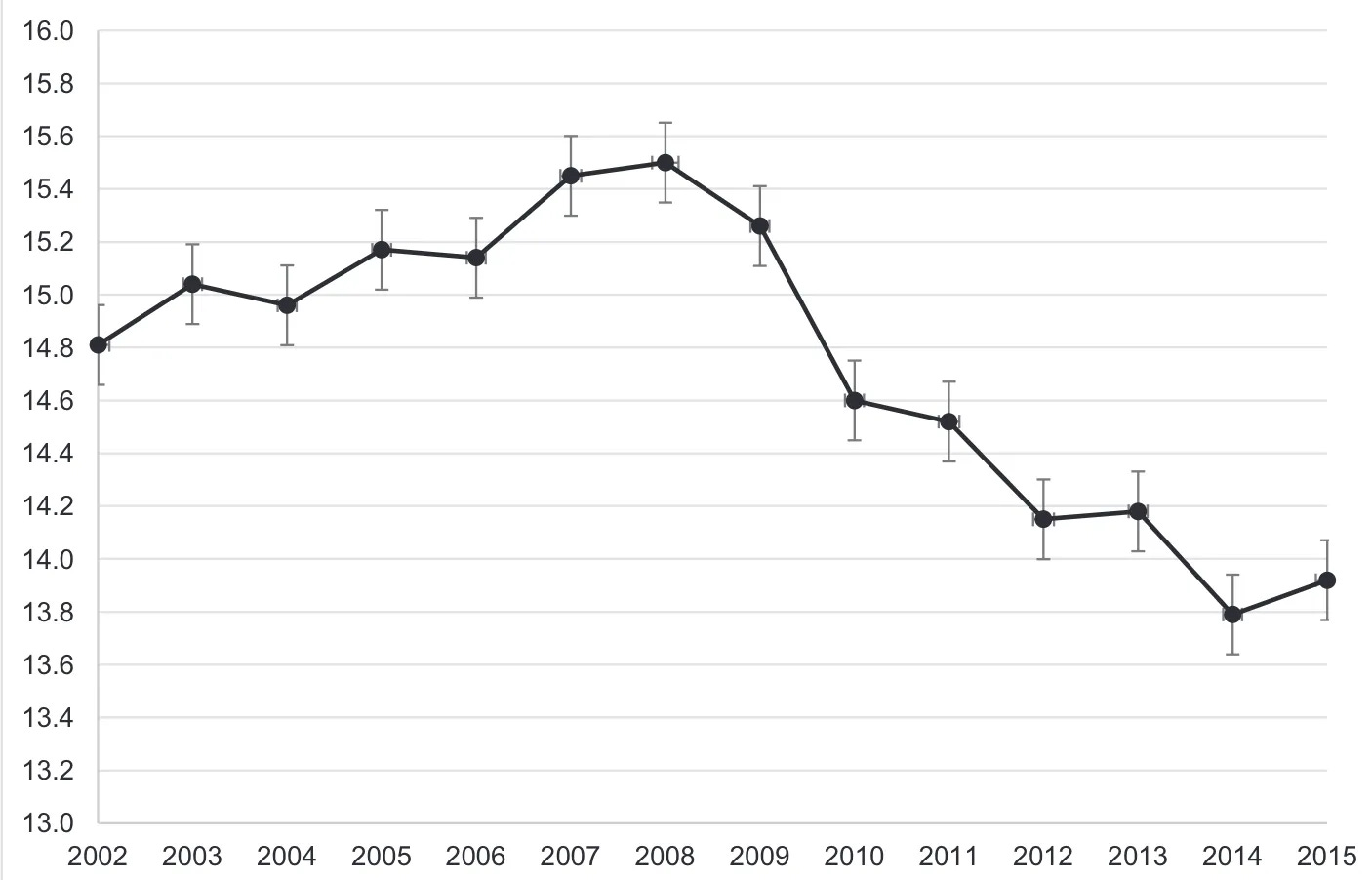

In Part 1 of this post, I started with a summary of research that suggested that narcissism was on the increase. Most of the data sets seemed to end a decade or more ago. The investor Joachim Clement picked up on this point in a post on narcissism he wrote earlier this year. Here’s data from research from Jean Twenge published in 2008 on the prevalence of narcissism in US college students.

(Source: Jean Twenge et al, 2008).

Klement observes that your worldview tends to be influenced strongly by what happens in your formative years (18-25):

(P)eople who experience tough times during their formative years act less selfishly and are more interested in the common good than people who experience good times. In other words, people who have been in their formative years during and after the global financial crisis should score lower on the narcissism scale than previous generations.

So he’s interested in the data on the level of narcissism among after 2008. And 2021 data on US college students, also published by Jean Twenge, which continues the sequence through the Crash, supports this hypothesis:

(Source: Jean Twenge et al, 2021)

So it is possible to suggest—in the spirit of a weak hypothesis, lightly held—that the great wave of narcissism-driven populism that dominated the 2010s, is beginning to recede. Of course, this isn’t much of a consolation. Grandiose narcissists wreck everything they touch, and there is a trail of debris behind them that will take years to clear up.

j2t#466

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.