14 December 2024. Tourism | Time

The battle over over-tourism // Deciding when slower is better [#622]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for the less frequent publication schedule recently. I have been finishing an article, and I had forgotten how time-consuming that is. Have a good weekend.

1: The battle over over-tourism

Notre-Dame Cathedral has reopened after more than five years of restoration since the catastrophic fire in 2019. At least the re-opening ceremony last week gave Macron a brief chance to look Presidential.

But more interesting are the rows it has generated about the costs and benefits of tourism. The French Culture Minister Rachida Dati has suggested that the church should charge €5 admission to tourists, as way to help pay for crumbling churches across the country, and the Notre-Dame authorities have so far pretty much completely ignored her.

(Notre Dame. Photo: Pedro Szekely/ Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

A €5 fee would raise an estimated €75 million a year. An article in Le Monde, partially behind a paywall, suggested that €5 was nowhere near enough:

Yes, a paid ticket should be introduced. And not for €5 – for 20 or 30. Not just at Notre-Dame, but at the cathedrals of Chartres, Bourges, Reims, Strasbourg or Amiens.

The rationale is that the cost of maintaining the country’s built heritage “is a bottomless pit”:

Three-quarters of France's 42,000 churches are located in towns with populations of less than 3,000 that have no means of maintaining them. Doing nothing presupposes a strong belief in miracles.

But underlying this argument is also an argument about the way that modern tourism works, with an increasing concentration on a small number of world class heritage locations—Notre Dame in particular (and Paris in general) is one; as is Florence; as is Barcelona; as is Venice. And so on.

[Notre Dame] attracts a thousand times more globalized tourists than worshippers. Before the fire in April 2019, the cathedral was the most visited site in Europe, attracting 12 or 13 million tourists per year. There will be 15 million after December 8: 40,000 people a day, who will be able to reserve a time slot on a platform set up at the end of November. Think the Louvre or Versailles, only hotter.

Of course, conventional economics suggests that if people have to pay €20 or €30, the number of admissions will fall. And they probably will, a bit. But the economics of tourism suggest that the economics of must-see attractions such as Notre-Dame are fairly inelastic:

[T]he farther a visitor travels, the more they accept to pay the full price in front of an exceptional site to which they will never return. The climate crisis also justifies a surcharge: 95% of tourists are concentrated on less than 5% of the planet's sites, straining the most popular monuments.

The concept of ‘over-tourism’ was invented by Skift in 2016, after annual tourism journeys passed the one billion mark. I’ve been collecting stories of over-tourism over the summer. (In truth, this wasn’t that hard, since The Guardian ran a series on it). Here’s some examples of the politics of this:

Barcelona gets 32 million visitors a year, which represents 14% of the city’s economy. But it costs €50 million to cover the extra financial cost in security, public transport, maintenance and cleaning. The bins in Las Ramblas have to be emptied 14 times a day. The daily tourist tax has recently been increased from €3.25 to €4, but it needs to be €6 to cover these costs.

In Spain over the summer tens of thousands of people took to the streets—“from Malaga to Mallorca, Gran Canaria to Granada”—to call for curbs on mass tourism.

Florence has announced a 10-point plan to tackle over-tourism—included a ban on keyboxes on properties. These are used to allow tourists to let themselves into holiday apartments. Earlier, protestors had taped keyboxes closed and painted a red ‘X’ on them. Almost 8 million people visited Florence in the first six months of this year.

Venice has 30 million visitors a year, and earlier this year it introduced an entry charge, of €5 a day, on a limited number of days, along with other restrictions. It seems to have had little effect on numbers. It’s doubling the fee in 2025 and extending the number of days in 2025, amid general scepticism that this will make any difference.

Amsterdam has banned cruise ships to limit tourist numbers and reduce pollution.

There are two things that usually drive the protests against over-tourism, apart from the sheer weight of numbers in the city centre. The first is the way in which tourism economics change the character and the culture of the city centre—in Barcelona, the cannabis shops are concentrated in the high tourism areas.

The second is about housing, as landlords pull housing out of the long-term local rental market to turn them into short-let holiday apartments. In turn, this has been a significant contributor to increased housing costs.

This is always right at the heart of protests about over-tourism. It’s worth unpacking this, because there are multiple things going on here.

The first is just the scale of the increase in the volume of international tourism over the last 70 years: a 25-fold increase in numbers since the 1950s. (There’s a string of films in the 1950s, from To Catch A Thief to Roman Holiday to Three Coins in the Fountain that basically teach people how to be international tourists.)

Some of this is down to increasing incomes—including increasing incomes in Asia—and some is down to cheaper and cheaper flights. In a long piece Zoe Williams notes that in 2023 1.3 billion people crossed international borders as tourists (although some of these will be multiple crossings by frequent travellers), and that tourism accounts for more than 8% of all carbon emissions.

But more of it is down to both the cultural and technological restructuring brought about by the world wide web. In their classic 2000 book Blown to Bits, Philip Evans and Thomas Wurster discuss disintermediation as one of the ways in which the economics of information would change business strategy.

(Source: Evans and Wurster, Blown to Bits)

There were disintermediators before: but they would head towards lower value customers and deliver thinner service. It was a different business model, and it came up against limits. (In tourism, think about the development of the package holiday as an example of trading richness for reach).

In an information business, everyone can construct their own holiday, and everyone with some capital can, until local jurisdictions prevent it, construct their own holiday provision. (I was struck by this travelling through Verona recently, where I stayed in an apartment near the station in a residential block that had been turned into accommodation for travellers.) And this is pretty much exactly what has happened.

In the piece about Barcelona that I quoted higher up, the writer, Xavier Mas de Xaxas, says this creates business people with no interest in the life of the city:

How can you build a community-based city when the owners of the buildings, the apartments, the shops and restaurants have no ties to Barcelona except to extract maximum profit?

And Barcelona is basically trying to push the city’s tourism strategy back up the line, towards richness and away from reach, by discouraging low value travellers (British stag and hen parties come up a lot in the articles). In her piece, Zoe Williams suggests that the problem is late capitalism:

[H]istorically, the inconvenience of having vastly more visitors a year than there are residents has been offset by what this does for the local economy. But, if the fruits, one way or another, aren’t evenly distributed – maybe the model drives a low-wage culture, maybe intermediaries such as cruise companies or Airbnb cream off the profit – that contract is bust.

But the other half of this is about the culture of mass tourism in the digital age. Just as the music and sports businesses have become ‘winner-take-all’ markets, so a small number of cities have become desired destinations (even if they don’t think of themselves as ‘winners’).

This is because the audio-visual culture created by the smartphone is a form of mimetic desire. For many tourist, especially for people who have the opportunity to travel internationally for the first time, the point is both to be there, and to be seen to be there.

In her book The New Tourist, published earlier this year, Paige McClanahan describes this kind of person as an ‘old tourist’,

a pure consumer who sees the people and places he encounters when he travels as nothing more than a means to some self-serving end: an item crossed off a bucket list, a fun shot for his Instagram grid, one more thing to brag about to his peers.

This does at least suggest that there are limits here. Eventually a degraded experience means that some people, at least, will go elsewhere. But these limits are not enough to fix the problem.

I expect that cities will find ways to increase the cost of being a tourist, way beyond the small change of current entry fees. LeMonde is clearly right about the kind of fee that the Notre Dame could afford to charge.

Costs of tourism will also increase as travel operators, especially airlines, are forced to increase their prices to cover their external costs, including contributions to emissions (think what a sensibly priced carbon tax might do.)

And it’s also clear that cities are finally getting to grips with the short-term rentals market, and seem to be learning from each other. Barcelona will ban short-term rentals within the city from 2029. New York City has introduced rules that a homeowner must be present in the property alongside their guests. Honolulu requires a lengthy minimum stay of 90 days.

Some cities have more complex strategies. Porto allows short-term rentals in neglected parts of the city where the tourist income might help the neighbourhood. In Spain, the protestors insist they are not against tourism, but against unbalanced tourism:

“We’ve reached the point where the balance between the use of resources and the welfare of the population here has broken down”... said Víctor Martín, a spokesperson for the collective Canarias se Agota – The Canaries Have Had Enough.

Paige McClanahan thinks that this will be fixed by the rise of the ‘new tourist’:

The new tourist embraces the chance to encounter people whose backgrounds are very different from her own, and to learn from cultures or religions that she might otherwise fear or regard with contempt.

I think you probably have to fix the political economy first. These are second and third and fourth order effects of the expansion of the web, and we’re still working out how to deal with them.

2: Deciding when slower is better

I’ve been meaning to write for a while about a talk by the advertising guy Rory Sutherland on how we think about time. Sutherland has made a career out of being a provocateur in the ad industry, and has always been interested in how our views of what we do can be reframed by different behavioural perspectives.

(Usual disclaimer: I used to work at a business that had the same parent company as Ogilvy, where Sutherland works, and I used to bump into him from time to time at events.)

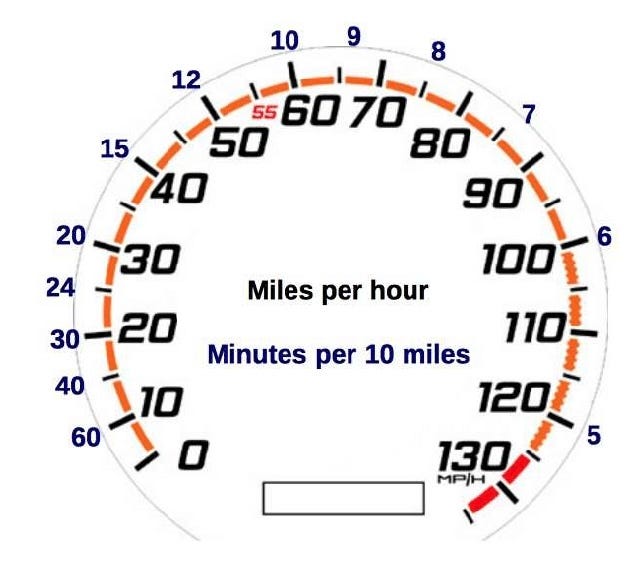

It’s quite a long piece, so I’ll take the performative bits out. Quite a lot of what he’s discussing is about time and travel. This image comes from his talk:

(Source: Peer, E., & Gamliel, E. (2013). Pace yourself: Improving time-saving judgments when increasing activity speed. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(2), 106-115.)

It’s a speedometer, with an extra set of numbers attached to it. The inner circle is speed; the outer circle is time—the time it takes to go 10 miles. At lower speeds, going a bit faster makes a difference, but at higher speeds you save barely any time:

Some of you may have noticed this if you’ve got a GPS in your car. You’re driving on the motorway at 60, you realize you’re going to be five minutes late for an appointment, so you welly it. And after driving at an insanely fast and dangerous speed for about eight minutes, you suddenly realize your arrival time has only improved by one minute.

From cars he turns to trains, and the algorithms of online ticketing. There are in the UK two main rail routes from London to Exeter. A fast route goes from Paddington station, and a slower route goes from Waterloo via Salisbury. The slower route is cheaper and prettier. But unless you spell out to the ticketing platform that you want to go via Salisbury, it will direct you to the faster route, because it privileges speed over cost and aesthetics.

This is, he implies, the trouble with engineers. They’re a bit linear. But he wonders what what might have happened if we hadn’t given the brief for our troubled High Speed 2 rail line to railway engineers, and asked Disney to make some proposals instead.

(For marketing or brand consultants of a certain age this will sound like an exercise that used to be fashionable in brand strategy workshops: what would Toyota do if it had to deliver financial services? How would Sony address the beverage market? What would Virgin do with yogurt? It’s designed to make you look at a sector through a different lens.)

But back to Disney:

They would’ve said, “First of all, we’re going to rewrite the question. The right question for High Speed 2 is: How do we make the train journey between London and Manchester so enjoyable that people feel stupid going by car?” That’s the right question. It’s not about time and speed and distance. Those things only obliquely correlate with human behavior, with human preference.

He suggests that these approaches don’t get tried because they are too soft edged. They involve judgment. Politicians can’t defend them easily:

This is a massive problem in decision-making. We try to close down the solution space of any problem in order to arrive at a single right answer that is difficult to argue with.

There is another reason why time is obsessed over in transport, and this is a bit of a dirty secret, which Sutherland learnt from Transport for London:

Someone I know who is an expert at Transport for London found out that quite a lot of people, quite a lot of the time, actually enjoy commuting... So this person announces the research to the people responsible for transport modeling at Transport for London, and they say, “You must never tell anybody that. It’s absolutely wrong for you to say that people might actually enjoy a train ride.”

If this seems perverse, especially if you are running a train service, the reason is this. As his expert was told,

'all our models that justify transport investment assume that travel time is always a disutility. In other words, the more time you spend in transit, the worse off you are.’

It’s worse than this: pretty much all of the investment models that the government uses to justify transport investment, especially road investment, are weighted in such a way that a few minutes of time savings make a big difference to the investment appraisal. Even though, as he says above, we barely notice those tiny gains in time.

He moves on to talk about the ways in which companies have tweaked our psychology about time to help improve our perception of a product. Uber didn’t get your car there faster, but they told you where it was and how long it would take to get there. Guinness, which needs to be poured very slowly, made a virtue in their advertising of patience bringing its reward.

And what this leads him into is a discussion about the ways that many of our systems are designed around the idea that we need to do things as quickly as possible, imposing this on us whether we like it or not:

[A]s an option, self-checkouts are great. As an obligation, they’re bad—because sometimes the time spent in the process is where the value comes from. You can see this because people on a Saturday love nothing better than to shop in the most inefficient way possible. That’s basically what a farmer’s market is—let’s take a Tesco and reverse everything. You’ve got to go to seven different places to buy anything.

His final question is about the places in our life where slow would be better. He hints at this earlier, when he says that email would have been better if every email had an automatic delay of two hours on it. (This would have made it about the speed of the 19th century London postal service, with six or so deliveries a day. )

I’ll end with a very weird question: What does slow AI look like? We’ve automatically assumed that the way we interact with it is instantaneous. Are we sure that’s right? Would it be interesting to be able to say to an AI, Look, over the next three or four months, can you give me some ideas about holidays in Greece?...

The general assumption driven by these optimization models is always that faster is better. I think there are things we need to deliberately and consciously slow down for our own sanity and for our own productivity.

j2t#622

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.