14 April 2023. Land | Business

‘Industrial wheatscapes have many ghosts’ // Getting to sustainable post-carbon businesses involves a change in worldview.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for the slightly erratic schedule. I’m away at the moment. Have a good weekend.

1: ‘Industrial wheatscapes have many ghosts’

One of the most interesting things I have been involved in over the last eighteen months or so has been a private discussion group on what might be called, broadly, the ‘more than human’ futures. I can’t say much more than this, because the group has quite strict rules on attribution, but I should acknowledge that it is hosted by the Sustainability Accelerator, and that the participants are a mix of futurists, academics and others interested in the area.

At a recent meeting, we invited Maya Marshak, who is an artist who works on themes relating to agro-ecology, to share something relating to her work. Maya has been a member of the group since coming to the Delfina Foundation (and supported by Chatham House) as an an artist in residence.

With the permission of Maya and the group’s convener, I am sharing here her text, which she read to us to start the session off.

The opening instruction as we started the session was that we were to imagine ourselves standing in the middle of a wheatfield. I recommend reading it out loud to yourself, if you can.

(Wheatfield, by Francois Schnell/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

Industrial wheatscapes have many ghosts

these ghosts are;the ancestor wheats,

their relationships with people and places and the weather and history

the movement across time and geography,

the grains and wild grasses that grew alongside and in-between,

the oats, barley, sorghum, and millet,

the places that were home,

the small farms

the thriving ecosystems

the wild flowers and wild edibles

the plants that weren’t ‘weeds’

the recipes for lost or rare grains

the memories of those recipes,

the animals, confined to hedgerows and the margins, the hares, and the hedgehogs,

the endangered ronosterveld, the spider orchid and riverine rabbit

the sounds, of the tree sparrow, the insects drowned out by the scale of industrial land use,

the balance in the soil,

the nutrients that are never replaced,

the tall wheats that would fall over in the wind and their long roots and their relationships with the soil minerals

the scythes and the hard work of harvesting

the tools and practices that were deemed inefficient or unwieldy or slow,

the oxen,

the mills,

the ideas and knowledges and things that mattered,

that were undermined,

regarded as useless,

and unproductive

These ghosts move among the now living things,

these are

the priorities of yield and profit,

the rational scientific decisions,

the straight lines,

the wheat organisms that match machines

the short straws that don’t lodge in the wind,

the short roots that match these short straws

that suck up nutrients in different ways,

that don’t know the soil organisms,

the pesticides,

the fungicides,

the herbicides,

of herbicide-resistant plants,

the alopecurus myosuroides casting its tall shadows

the breeding technologies,

the research stations,

the ownership of seeds,

the dispossession,

the seeds in seed banks,

in vaults,

the field trials,

the Chorleywood Baking Process,

the instant yeast,

the white bread,

the abundance,

the waste,

the fumigated silos,

the saved time,

the saved costs,

the costs

the silence of monocrops

and the noise,

the predictability,

the unpredictability,

the changing weather these days,

the fear of drought, of too much rain,

the rhetoric of seed companies,

the dialogue on food security,

the control,

the reclaimed seed,

the planting of it,

and sharing,

and finding patterns again,

and relationships

and reconnections.

—

I’m not going to share the discussion that followed here, other than to say two things. The first is that the line on “hedgerows and margins” sparked a conversation about what had been squeezed to the edges by modern agriculture, which is in its different ways a creature of enclosure and a pressure to produce food for a growing global population. People, animals, insects, birds, and so on.

This linked to a conversation about the 19th century English poet John Clare, whose work was about the land and who was, possibly, driven to madness by land enclosures.

Without being too obvious, it was also a reminder of the ways in which approaching subjects in a completely different way, with very different stimulus, can generate rich outcomes when handled carefully.

At the end of the conversation, we were invited to walk from the middle of the wheatfield and pick up an object from it as we went.

2: Getting to sustainable post-carbon businesses involves a change in worldview

I wrote last week, in my account of David Bent’s talk on business transition, that resolving the conflict within businesses between the short-run assumptions of finance and the long-run requirements of the transition is a critical issue. Moving businesses from being ‘time-blinkered’ to ‘long-minded’, perhaps. And this reminded me that I’d written about some of this in a client report a couple of years ago. Here’s a version of that with client bits taken out. It’s long, so I’ll break into two parts.

This conflict is partly an argument about the difference between 20th century businesses and 21st century businesses. They live by different metaphors. The metaphors of the first are about Newtonian physics and mechanical engineering. The metaphors of the second are about complexity, emergence, and ecological systems.

In one of the strongest statements of this argument, Eric Beinhocker argues in The Origin of Wealth,

“wealth creation is the product of a simple but powerful three-step formula—differentiate, select, and amplify—the formula of evolution.”

This understanding is not new. In the UK alone it can be traced back to management thinkers such as Geoffrey Vickers, F.E. Emery, Peter Checkland and Stafford Beer, all writing in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Apart from a universal trend in all disciplines towards complexity thinking—“the complexity turn” described by John Urry—there are three trends that have combined to bring this change into the mainstream.

These are:

(1) the long run shift to a services and knowledge economy, which places new demands on employees to bring their whole selves to work, even in low-paid jobs in retail or hospitality;

(2) the spread of digital and distributed technologies, which blur the edges of the organisation;

(3) the shift in values held by citizens and customers, from extrinsic public facing values to intrinsic personal values.

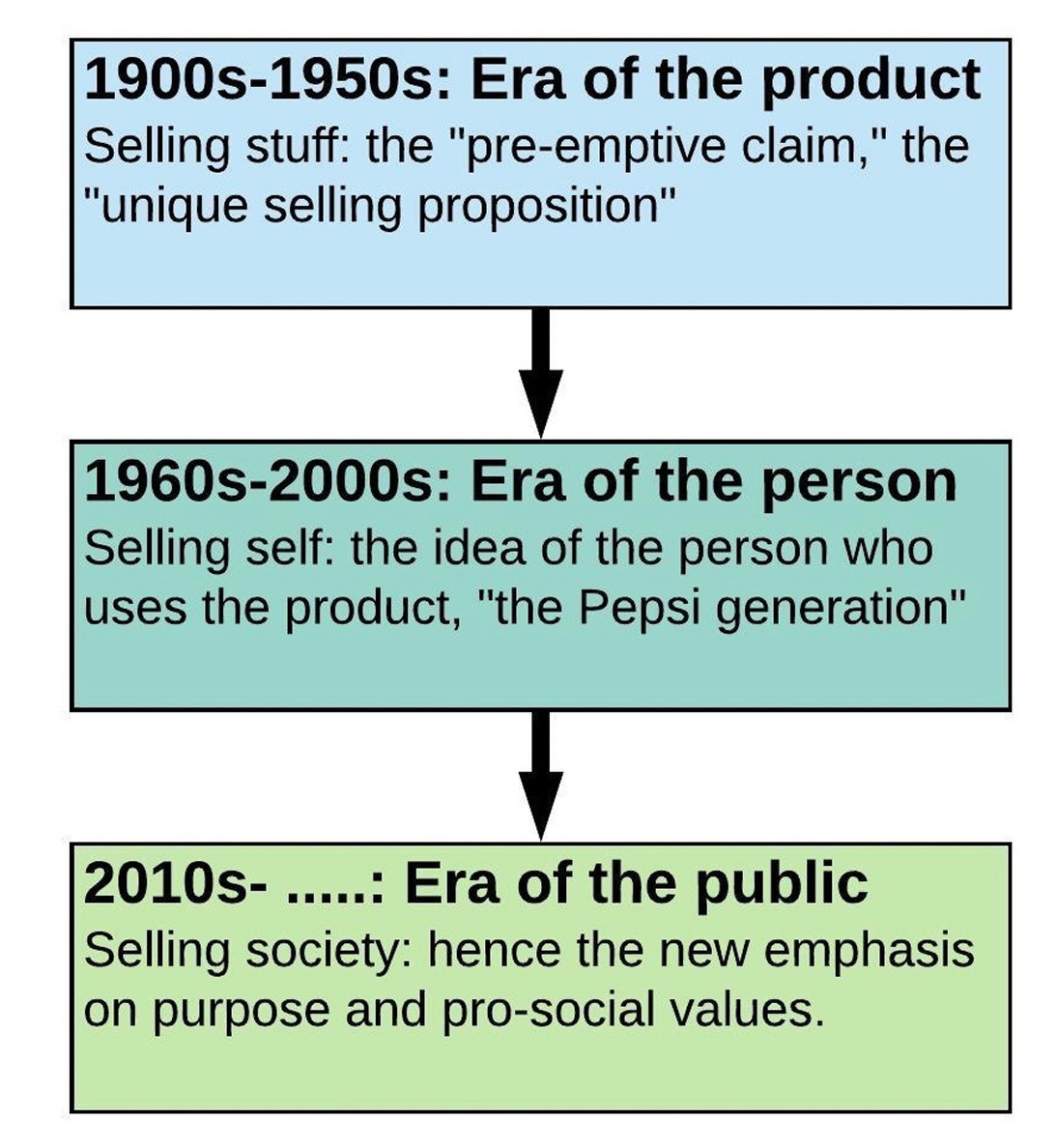

One consequence of this has been a transition in the world of brand and marketing behaviour. If brands responded to the ‘boomer’ generation by moving from ‘selling stuff’ to ‘selling self’, they are now ‘selling society’. My former colleague Walker Smith, says this is a ‘third era’ of marketing and branding, which he calls the ‘era of the public’. (Yes, marketing eras need to be counted in dog years.) This means that businesses are now expected to have a clear view of their business purpose, although this sometimes sits uncomfortably with them.

(Source: J. Walker Smith, Kantar Consulting)

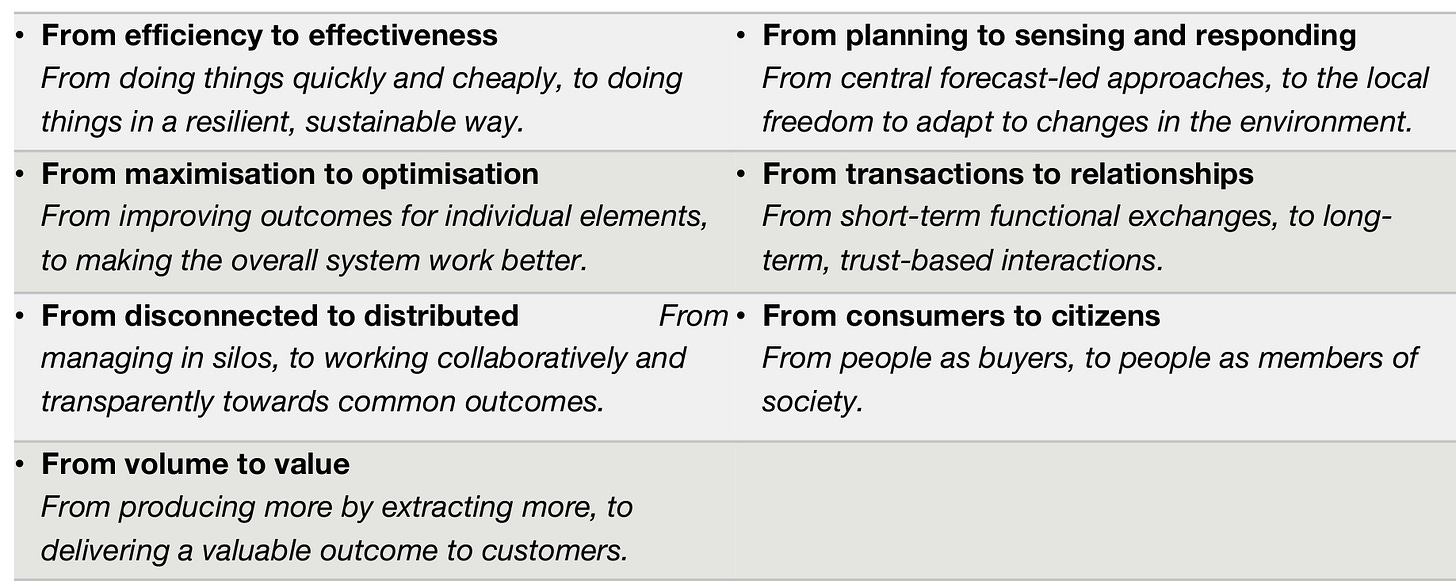

In turn, this means that the way we understand business is moving from complicated to complex. In a complicated world, cause always has the same effect, and parts are interchangeable. “Efficiency” is a metric of the complicated world. In a complex world cause and effect are inter-related and the outcomes of interventions are unpredictable. We’re still learning how to manage businesses in a complex environment. As the business writer Simon Caulkin says:

“Ecosystems represent a historic evolutionary shift in the ecology of business which offers vast potential for new kinds of value creation. But making the most of it requires an equal evolutionary advance in thinking about the form and functioning of the organisations that animate those ecosystems. The first law of systems is that everything is connected to everything else. The second law, obvious when you think about it, is that you can’t optimize a system by optimizing the parts.”

The table below, adapted from a report I wrote with Jules Peck a decade ago, summarises some of the directions of travel.

(Source: adapted from Curry and Peck, ‘The 21st Century Business’, The Futures Company.)

It’s worth stepping back a bit for a moment. Companies are people. The root of the word is in the Old French, compagnie, for “society, friendship, intimacy”. The Tomorrow’s Capitalism project has built on this to describe the different roles played by a company. Companies are: citizens; producers; customers; employers; and investors.

In theory, when these roles are aligned, then the organisation can move ahead purposefully. When they are not, you end up with what the economist Kate Raworth describes as a corporation with a split personality. Different roles—sometimes enacted by the same people—pull in different directions. For example, even when you look at businesses that have made significant public commitments to sustainability, you will usually find that many managers still have KPIs based on the volume of goods they are able to shift.

So the model of the emerging company needs to do more if it is going to be useful.

It needs to help us to understand both the roots of these kinds of internal conflicts, and the actions the businesses can take to resolve them. One way through this is offered by the management thinker Richard Normann. Drawing on the classic 1950s text Leadership in Administration, he proposes a model that connects different aspects of the organisation with the outside world.

The organisation has two touchpoints, in effect. One is with the business and economic institutions that frame what Normann calls the “dominant value creating logic” of the time. These include investors, of course, but also all of its exchanges with other organisations in its value chain or value network. The second is with customers, through its “value commitments”. Internally, these are articulated through the soft elements of purpose and values, and the harder shell of its organisational structure.

Value commitments are a way to create narratives about business purpose that involve having some kind of skin in the game. They also tend to be attacked if they are at odds with the value creating logic. The role of a “value commitment” is as a concrete statement of intent that is designed to defend the company’s purpose and structure. But value commitments are also a way to move a company’s values forwards, to change expectations about the business. To give one example here: Cynthia Carroll’s commitment when she was CEO of the mining company Anglo American to “zero harm” (no fatalities or serious injuries) was a value commitment, designed to improve Anglo’s safety culture. It was a concrete statement: people would be know if she had succeeded or failed.

In Part 2, on Monday, I’ll tease this out to suggest what it means for business and the post-carbon transition.

j2t#445

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague