13 November 2023. Future images | Dylan Thomas

Looking at the future from the past // Thinking about Dylan Thomas [#514]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Looking at the future from the past

I was doing a little bit of picture research the other day, and I came across an article about illustrations from the 19th century imagining the long term future. I know quite a lot of these images—I often use them when I’m doing futures learning as a warm up. In particular, in late 19th century France there seemed to be a lively market in images of the year 2000, for reasons I’ve not yet managed to understand.

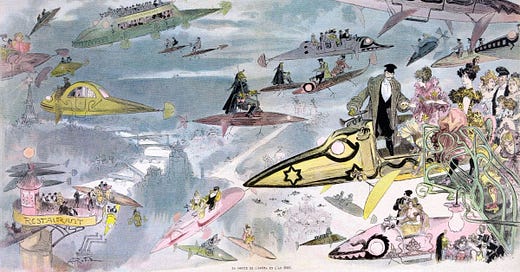

One of the leading French artists was Alfred Robida, who was interested in both the future in the air and also audio-visual communications. Here’s his ‘Leaving the Opera in the Year 2000’.

(Albert Robida: “Leaving the Opera in the Year 2000,” published in 1882.)

What intrigues me about this image is the date: 1882. At that time, the only aerial objects were hot air balloons, but the French Navy had developed a powered submarine 20 years previously, which might be why these flying machines look a bit like submarines. When I talk about this image, I remind people that it’s possible to imagine future technologies even if they aren’t yet able to build them.

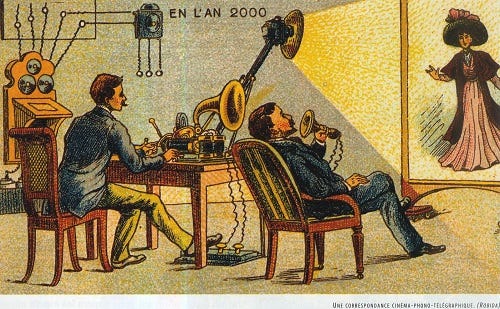

It’s not included in the article, but Robida also has a well-developed line in audio-visual futures.

(Albert Robida: “Telephonoscope in 2000,” published in 1883.)

There’s a projector showing the a woman on screen who is being talked to through a telephone. Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone about five years ago, but the cinema was still 15 years away. All the same, there were a lot of 19th century visual technologies that created the idea of visual movement.

There’s a similar set of ‘year 2000’ photos developed by Robida’s French near-contemporary Jean Marc Côté, published in 1899. Flight appears here—a flying rural postman, a helicopter—but there are various other technologies at play here as well. We have these images more or less by chance:

In the early 1920s, a set of 100 postcards were discovered in an abandoned French factory basement, amongst shelves of dusty novelties and circus automatons. From there they sat in an Editions Renaud, a Parisian antique shop for over half a century, until they were bought in 1978 by author Christopher Hyde.

They had been commissioned by the manufacturer Armand Gervais to mark the “fin de siècle festival” of 1899. Here’s one that seems to be an early version of the “food-to-pills” futures trope that reappeared endlessly through the 20th century.

(Jean Marc Côté: “A Chemical Dinner Party.”, published in 1899.)

One of his other 1899 images has a front room being heated by radium, discovered the previous year. This was before we discovered the side-effects, of course.

An English image from the same decade combines uses aerial technologies to solve a big urban problem of the time—that the streets were dark at night. This is by Fred Jane in Pall Mall Magazine, and I like the honesty of the title: “Guesses at Futurity”.

(Fred Jane: “Street Lighting, AD 2000”, published in 1894).

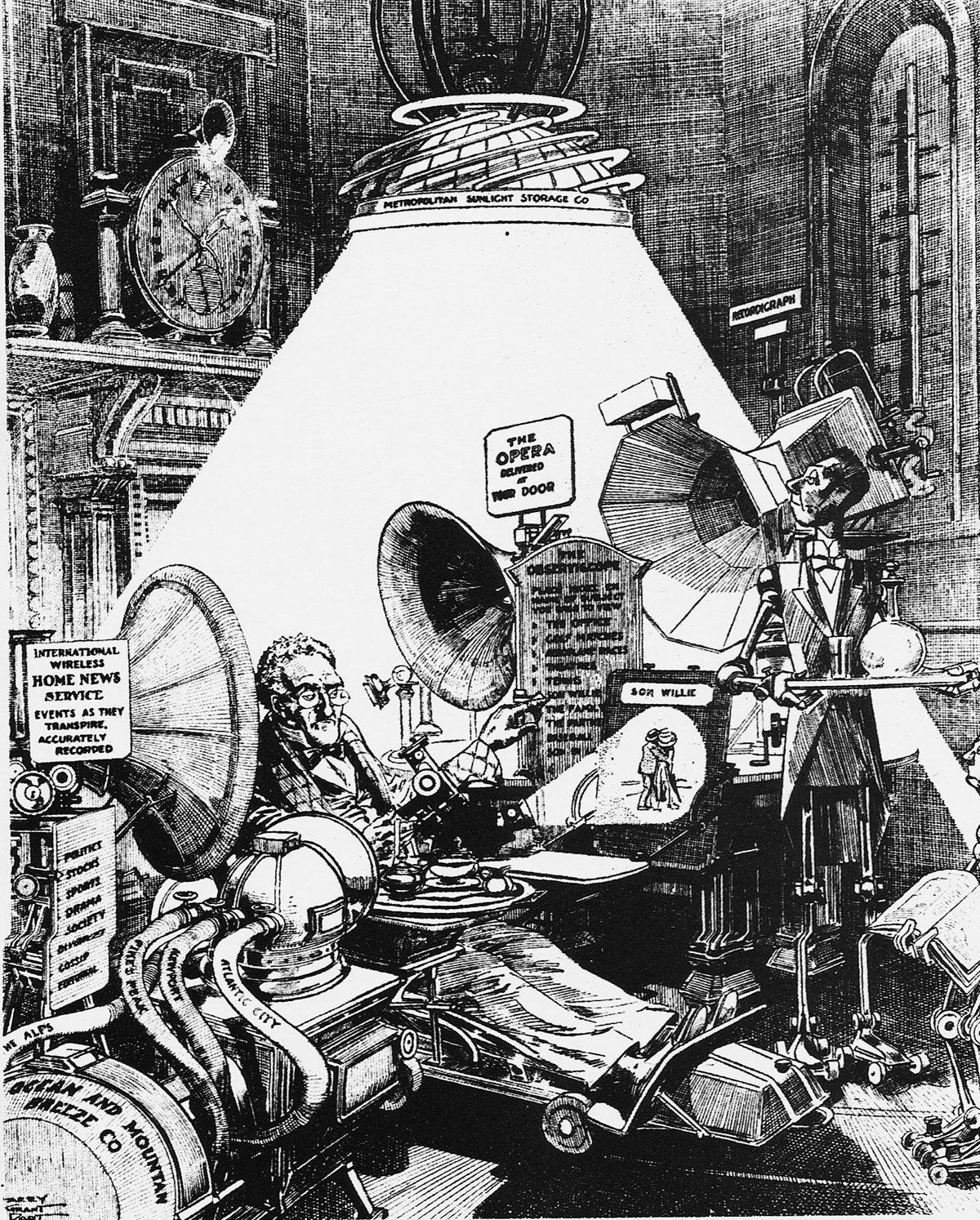

Some of the future images in the article are intended satirically. I hadn’t come across the work of the American illustrator Harry Grant Dart before, for example:

He was also a cartoonist for Life and Judge magazine, where his satirical cartoons were less optimistic than many of his futurist contemporaries, channelling anxiety and paranoia about where technological change might lead. “We’ll All Be Happy Then” shows a mishmash of devices designed to enhance our domestic life: stored sunlight overhead, fresh air pumped in from the Alps, opera delivered to your speaker, 24-hour news with “events as they transpire, accurately recorded.”

(Harry Grant Dart: “We’ll All Be Happy Then”, published in 1894.)

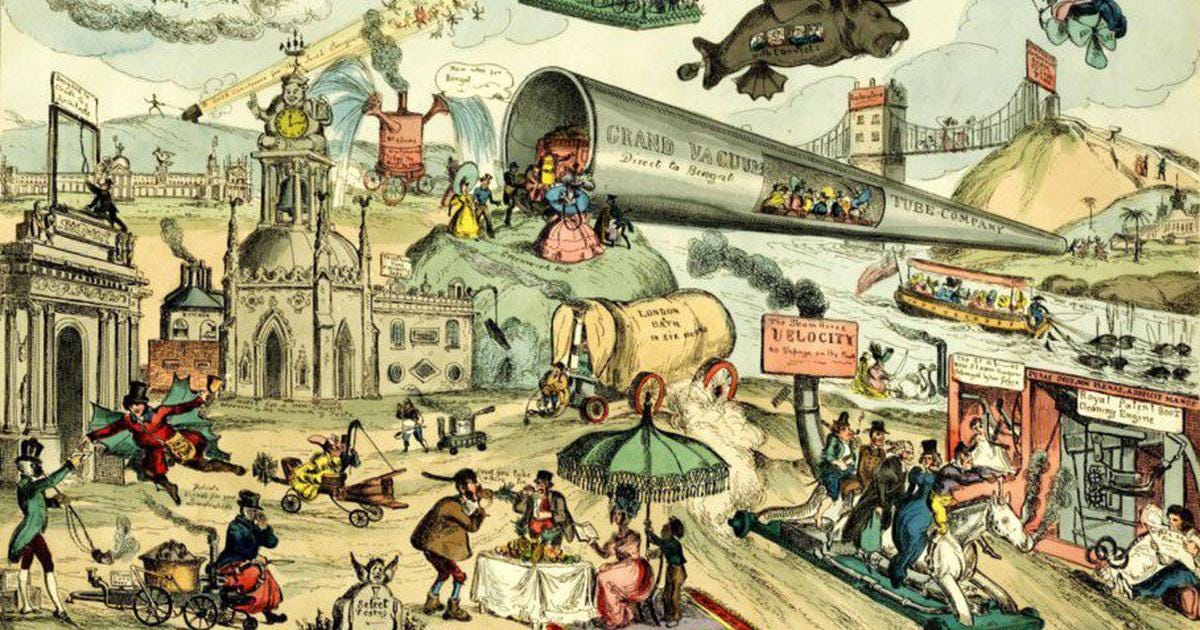

From much earlier in the century, the cartoonist Willian Heath similarly satirised the industrialist Robert Owen’s description of “the march of the intellect”, intended to highlight the big strides being made in human knowledge at the time:

His excitement was openly lampooned in a series of prints by William Heath: with mocking enthusiasm, Heath depicted a plethora of future transport methods, including steam horses, vacuum tunnel transport from London to Bengal, flying mail carriers (which would become a futurist trope), and Irish immigrants being fired from a giant cannon (reflecting topical social prejudices).

(William Heath: ““Lord how this world improves as we grow older”, published in 1828.

Vacuum tunnel transport? Anyone would think that Elon Musk had got his futures thinking from William Heath. Robert Owen probably didn’t deserve Heath’s scorn, since he was a progressive industrialist who used technology to improve the circumstances of his workers. All the same, one of the things I took away from the article is that we might benefit from some better satire these days of some of the more self-serving future visions of our business and political elites.

And of course, one of the striking features of all of these images is that in the future, the technology changes, but the clothes and social relations remain frozen in time. But that’s always much harder to imagine.

2: Thinking about Dylan Thomas

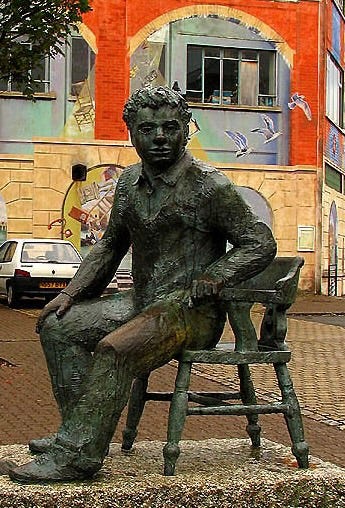

It was seventy years last week since the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas died in New York, and the BBC marked the occasion by re-screening some of their programmes about Thomas. This is one of the benefits of a public service broadcaster with a big archive and a mission to educate, entertain, and inform.

(Statue of Dylan Thomas in Swansea’s Maritime Quarter. Photo by Pam Brophy/geograph. CC BY-SA 2.0)

There was an Arena programme about Thomas’ life, told backwards, made for the 50th anniversary of the death, in 2003, and a television production of his ‘play for voices’, Under Milk Wood that marked the centenary of the poet’s birth in 2014.

Sadly, this mini-season didn’t include (even on iPlayer) a re-screening of Owen Sheers’ programme that set out to reclaim Thomas’ poetry from the noise about his life. All the same, some rapid research revealed that the TV programme had been based on an introduction to a new (in 2014) Selected Poems from the Folio Society, that a version of this had been published in the Financial Times, and that he’d appeared on a Radio 4 programme as a guest telling a similar story. Kudos to any freelance writer who can make his material work so hard for him.

I was brought up, mostly, on the rock ‘n’ roll myths of Dylan Thomas: the mercurial spirit, always in debt, who lived fast (mostly on booze), treated his family badly, and died at 39. His death, in the Chelsea Hotel in New York on his fourth tour of America, overshadows his life. John Brinnin, who had arranged the US tours, claimed that Thomas had drunk 18 whiskies the night before his death (these would be English doubles), “an insult to the brain”.

This was untrue. In the Arena documentary, the presenter Nigel Williams describes it as myth-making. Thomas had been unwell before he left Britain. Another member of the tour entourage, the slightly sinister Dr Feltenstein, had kept Thomas going with a grim mixture of injections of uppers and downers. Now he injected Thomas—suffering from advanced bronchitis and pneumonia—with half a grain of morphine. Thomas lapsed into a coma from which he had never recovered. As Sean O’Brien once wrote of Lowell George, “I wish you had not found such special friends.”

Williams found plenty of people willing to attest that Thomas was a drinker not a drunk, who typically ordered halves of bitter—if sometimes a lot of them—and says that during his period in the post-war years working as a writer and an actor for BBC Radio, his reputation seems to have been mostly for reliability. Which is not to say that his relationship with his wife, Caitlin, was not tempestuous and sometimes alcohol-fuelled.

Of course, the fact that I have to say all of this first speaks to the difficulty of writing about Dylan Thomas as a poet.

From these various sources several things stood out about the poetry. The first was how precocious he was. His first published poem, “Light breaks where no sun shines”, appreared in The Listener (a well-respected magazine then published by the BBC) when he was 18. It made enough of an impact on T.S. Eliot for Eliot to find Thomas’ address—he was still living at home in Cwmdonkin Drive, Swansea—and send him a letter congratulating him.

“And death shall have no dominion”, which appears in his second collection, which is a formidable piece of work, was written when he was 19. As a writer he was mature beyond his years.

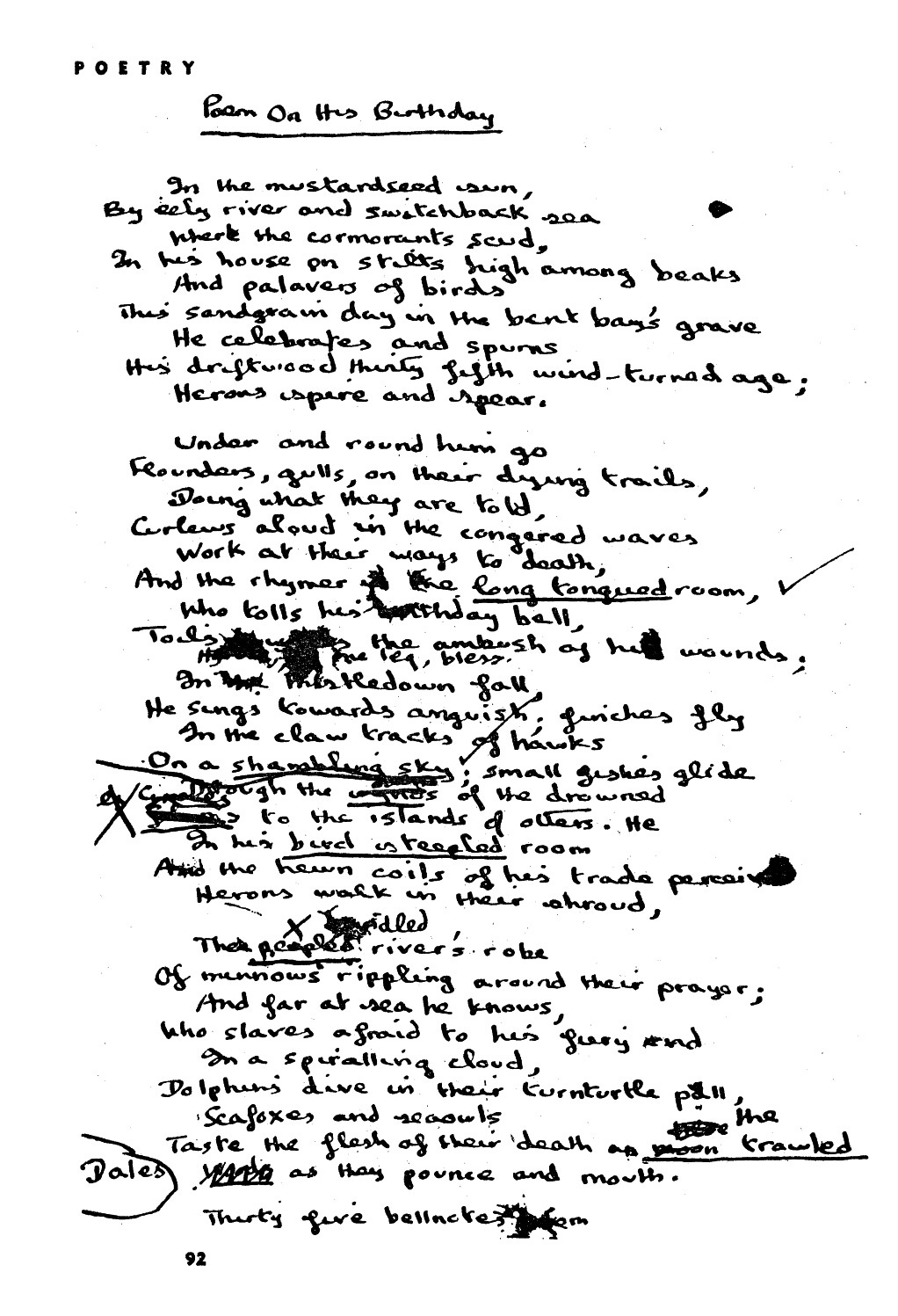

(Poem on His Birthday. Facsimile draft. Source: Poetry Foundation).

The second is how hard he worked at his poems, often weighing each word. There are said to be 200 worksheets relating to his “Poem on his Birthday”. Some of these are lists of synonyms that he is testing for a particular line.

In the Arena documentary, Nigel Williams quotes Thomas’ friend Vernon Watkins, who said that that Thomas took three weeks to write “I Make This In A Warring Absence”, which is a kind of a love poem to Caitlin Thomas, if an obscure one, and that it took him another four days to decide to change, slightly, the last two lines—which he later rewrote again.

Technically, a lot of these poems are demanding. They have complex rhythms, unusual rhyme forms and combinations of full and half rhymes. Sometimes the language is colloquial and seems to be effortless; other times it is dense and allusive, and needs the listener or reader to do some work.

The third thing learned was how influential he had been. I’d always thought of him as interesting but a bit lightweight, more a performer than a poet. But his post-war collection Deaths and Entrances, published in 1946, sold 10,000 copies, a huge number then or at any time. At the time of its publication, and afterwards, he was in his mid-30s the most famous poet in Britain.

The volume includes favourites such as “Fern Hill”—there’s a recording of King Charles reading this in 2013—and “Poem in October” (‘It was my thirtieth year to heaven’, of which there is a youtube video below), as well as a set of poems that come to terms with the griefs of World War II, notably “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London”. In his Financial Times article, Owen Sheers writes of “A Refusal”:

In this poem Thomas writes an elegy about how to elegise, refusing to mourn the child publicly, and then doing just that in extending the idea of “public” to take in a deeper, longer vision of all mankind and time.

But the collection also includes some poems which play with the visual shape of the words on the page, in the sequence “Vision and Prayer”, where the text makes diamonds and crosses on the page.

(Cover of a first edition of Deaths and Entrances, from a Sotheby’s auction catalogue.)

Thomas went to the US four times on tour, and did 150 readings in three years, with all the associated meeting, greeting and receptions that went with that. He was a sensation—early on, shows were upgraded from 300-seater theatres to 1,000 seats—and he did it because he saw it as a way of clearing his debts. All the same, he apparently hated it because it was impossible for him to write while on tour.

But he was influential here too. He met the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg on one tour; another of the Beats, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, has cited him as an influence (and, much later, wrote a poem in Thomas’ memory.)

This was Philip Larkin’s response to the news of Dylan Thmas’ death, from Sheers’ Financial Times article:

“I can’t believe DT is truly dead,” he wrote on being informed of Thomas’s death in New York in 1953. “It seems absurd. Three people who’ve altered the face of poetry and the youngest had to die.”

The other two members of Larkin’s trinity who had “altered the face of poetry” were T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden.

j2t#514

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.