13 January 2023. Batteries | Unicorns

The plummeting cost of batteries. // The deep cultural history of unicorns.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Have a good weekend.

1: The plummeting cost of batteries

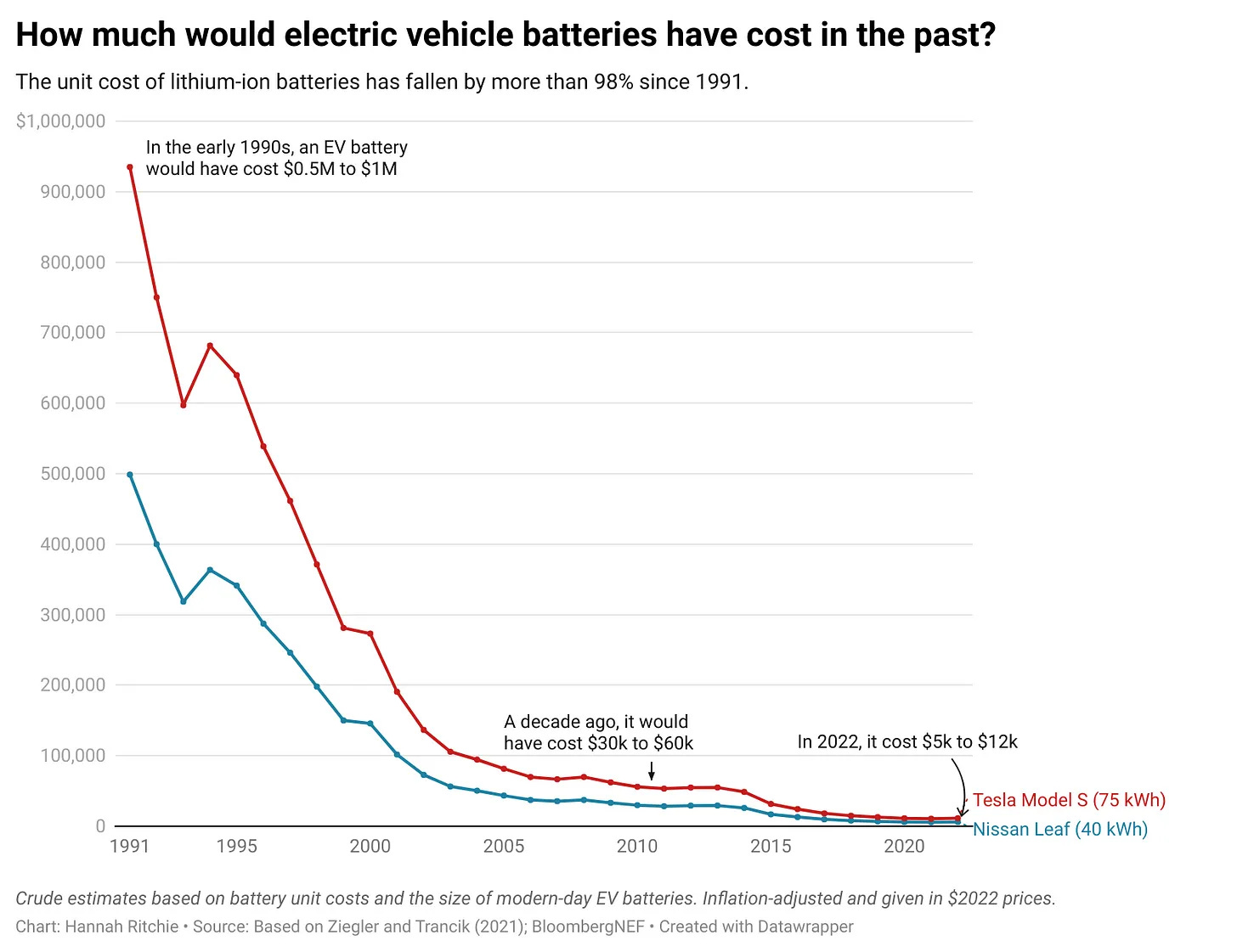

At her recently launched Substack ‘Sustainability by Numbers’ Hannah Ritchie has been running some numbers on the speed at which the costs of electric batteries have fallen. She shares her calculations in the piece, which she says are a mix of a reconstructed data series and some back of envelope calculations. She’s constructed some sums working backwards from the current Tesla Model S (with a 75 kWh battery), and the cheaper Nissan Leaf (40 kWh).

Her conclusions are dramatic, and it leads her to the view that the take-up of electric vehicles is going to be quicker than we expect, partly because batteries are typically the most expensive component in an EV:

The battery in a Tesla Model S costs around $12,000 today. In the early 1990s, it would have cost just shy of a million dollars. The battery in a Nissan Leaf is smaller and costs around $6,000 today. In the early 1990s, it would have cost almost half a million dollars.

Here’s her chart, which takes a 30-year view of prices:

(Source: Hannah Ritchie, Sustainability by Numbers)

Although these numbers look spectacular, they are the sort of performance you get when a technology scales quickly. You get gains from two places: economies of scale (things get cheaper when you produce more of them) and economies of scope (as you make more of them, you also learn things about how to produce them that also make them cheaper).

There’s a popular fallacy that these gains are somehow unique to the digital age, per Moore’s Law. As Santa Fe researchers demonstrated a while ago, ‘Wright’s Law’, which is more generic, is a better guide to falling technology costs.

And so, in the case of batteries:

We’ve worked out how to make lithium-ion batteries much more energy-dense – this means they get more electrical energy per liter (or unit) of battery. In 1991 you could only get 200 watt-hours (Wh) of capacity per liter of battery.3 You can now get over 700 Wh. That’s a 3.4-fold increase. They’re not just cheaper, they’re much smaller and lighter too.

One of her conclusions is that this should make us more optimistic about the prospects for the transition away from fossil fuels and towards renewable- and electric-powered systems, where batteries are a critical technology.

She suggests that pessimism is often driven by two things:

They are looking at data that’s older than the last few years;

or, they’re looking at absolute numbers rather than growth rates.

Instead, we should be looking at the rate of change. And the acceleration in the share of EVs, across a whole range of markets, is remarkable:

Sales data from the last few years gives us some clues. Almost 10% of cars sold in 2021 were electric. That might seem small, but consider how fast this is growing: the year before it was 4%, and just 2.5% in 2019. In many countries, this percentage is much more: in Norway, almost 90% of cars sold in 2021 were electric; in the Netherlands, it was one-in-three, and in the UK and Portugal, one-in-five. It was 16% in China, tripling from 5% the year before.

So, being optimistic for a moment:

The transition to electric vehicles is here, and could happen extremely quickly. This is not only better for the climate (regardless of the electricity source), it’s better for local air pollution, and also provides a much better driving experience.

2: The deep cultural history of unicorns

It seems that humans have a deep need of unicorns. When I say unicorns, I’m talking here about horses with a single horn in their heads, not those imaginary start-ups that claim to be heading for a billion dollar valuation.

Anyway, this is the intriguing cultural argument made by the natural history writer Don Pinnock in the pages of the Daily Maverick recently. He stumbled across a second-hand copy of a book called A Natural History of Unicorns, by Chris Lavers, and has worked it into an article about the cultural history of unicorns. First, the way a unicorn looks depends on where you are standing:

A Christian background will give you a gentle, goatlike animal, generally in the presence of a beautiful maiden. With a more secular tradition, you’ll have a noble beast facing a lion across a coat of arms. In Africa, a unicorn is more likely to be a fearsome forest thing. If your parents were hippies it will be a magical airbrushed beast amid twinkling crystals. But somehow it’s always something and always with that startling, single horn.

(Unicorn spotted in the 1551 book ‘Historiae Animalium’ by Konrad Gessner. Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Unicorns go back into our deep history. Aristotle writes about them:

Aristotle spoke of an Indian ass with a single horn and Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, went further: “In India the fiercest animal is the monoceros, which… resembles a horse but in the head a stag, in the feet an elephant and in the tail a boar and a single black horn three feet long projecting from the middle of the forehead.”

The Bible is full of unicorns:

In Numbers 23.22, God brought the people of Israel out of Egypt: “he hath as it were the strength of the unicorn.” There are unicorns in Deuteronomy 33.17, Psalms 22.21, Psalms 24.6 and Isiah 34.7. The word has a Biblical history. In the ancient Hebrew text, it was a reem. In the Greek translation, it became monoceros; in the Latin version, unicornus and in the English translation, unicorn. Clearly, unicorns were of utmost importance to God, but difficult to observe in the wild. They were always, somehow, elsewhere.

The second century book Physiologus, translated widely from the Greek, includes instructions on how to capture unicorns:

“It is a very small animal like a kid, excessively swift with one horn in the middle of his forehead and no hunter can catch him. But it can be trapped. A virgin girl is led to where he lurks and there she is sent off herself into the woods. He soon leaps into her lap when he sees her and embraces her and hence gets caught.”

(‘Chastity (a virgin and a unicorn’). Oil painting by a follower of Timoteo Viti. (C) Wellcome Images).

There are tapestries from the same period showing large scale unicorn hunts, but even here the unicorn is not killed but rescued, apparently by a maiden who just happens to be to hand.

Strangely, just as the world opened up, unicorns were discovered by explorers.

Their spectacular horns, made from a substance later termed alicorn, began circulating in Europe and commanding huge prices. In 1609, one was said to have been valued at half a city. The king of France owned one valued at £20,000 (many millions at today’s prices). The British royal family owned one assessed at £100,000… Then, in the 1630s, the bubble burst. The Regius Professor of Denmark, Ole Worm , declared the horns to be the tusks of North Atlantic narwhals. Undeterred by truth, the mania continued for nearly 200 more years.

Of course, the British Royal family was so persuaded that unicorns were real that they included one in their family crest, I think following the Act of Union with Scotland.

And explorers continued to hope that unicorns might be found in the more obscure parts of Africa and Asia even as scientists declared that a mammal with a single tusk in the middle of its head was anatomically impossible.

All the same, reports of unicorns kept popping up:

The Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman said unicorns were common near the Cape of Good Hope and was presented with a horn… Philip Goss of the Royal Society questioned a witness in Mozambique about the ndzoodzoo, which was about the size of a horse, had a single horn and was extremely swift. The horn, he was told, folded up when the animal was asleep. Explorer Dr Eduard Ruppell was told of herds of them in Sudan. In 1848, Louis Ducoret fleeced the French Service de Missions of thousands of francs to find one on the grassy plains around Lake Chad.

Finally, the British diplomat and explorer Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston, who headed a Royal Society scientific expedition to East Africa, spent 17 years in the region in the late 19th century hoping unsuccessfully to find a unicorn.

In his piece, Pinnock notes, perhaps wryly, that the unicorn “holds the record of the longest history of any mammal that never existed”. It was striking to me that the history of unicorns goes so far back into our culture, and has persisted for so long. Perhaps we do need to believe in some idea of purity.

Update: ChatGPT does Dickens

Inventive pieces about ChatGPT just keep on coming. This time Henry Oliver plays with the software to write a scene in the style of Dickens between two Dickens characters from different books. Oliver’s article is interesting for two reasons. First, he’s open about the extent of the guidance he had to give the software to produce a decent outcome. It took him a while.

Secondly, he opens up an interesting question: Will ChatGPT open up a new chapter in fan fiction:

Perhaps there is a future new job emerging here. This has significant potential for use creating scripts based on novels. And for someone who knows the material, this seems to offer new ways of writing the sort fiction that carries on where famous authors left off. Is fan fiction about to become a more creative and significant genre?

j2t#414

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.