Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Dreaming of canteens

I wrote here on Saturday about Ruby Tandoh’s essay about fast food franchises being like “the living rooms of the city”—places where you could “just be” for a while, in exchange for a modest purchase.

This prompted Adam Englebright to send me a link to an article by Rebecca May Johnson from last year about the ideal canteen. Normally I’d just post that as an ‘Update’ or ‘Notes from readers’, but it is a fantastic essay. On the face of it, it seems utopian, until you get to the end of it, and discover that we’ve done something similar in the past.

'I Dream of Canteens’ starts by describing some of the characteristics of this canteen.

Space

There is a space for everyone. A space, a glass of water, and a plug socket. Chairs and tables and cleaned toilets. So many chairs so that no one is without one. Enough napkins to blow your nose or wipe your mouth. The chairs take different forms and there are chairs placed in designated areas (a praxis of positive discrimination).

Food is cheap. I can afford it and everyone else here can afford to buy it for themselves and their child without anxiety. There are no instances of that tightening around the throat when you do not have the money to buy food, but you are hungry and in a place that serves it. For those who have more money the price is a joyful novelty; for those who have less, the prices are a blessed relief.

People take their trays from the tables even thought there are no signs instructing them to do this. There are enough staff so that rubbish doesn’t build up, and the staff are not rushed off their feet.

Time

There is also time for everyone. No one is asked to leave and no one feels anxious about out-staying their welcome. Of course people do leave, but still, staying is not suspicious. No laminated signs about leaving or staying or eating food bought here or elsewhere are on the tables or the walls... no one who is hosted here will be asked to leave and everyone will be fed and watered and allowed to wash without question.

Well, the catch here is that Johnson actually started writing about some real cafes that she’d been doing some research on: the cafes that IKEA runs in its large edge of town superstores.

(Photo: IKEA)

Of course, IKEA has good business reasons for doing this—these stores involve a trip, buying furniture can be stressful, and the cafes it runs are therefore an investment that is designed to calm its customers. And a bit more than that—to create an idea that IKEA is indeed for everyone and values all of its customers.

The idea that mass catering must be devoid of pleasure is false. The levels of pleasure derived from eating a meal or drinking a drink without the anxieties of restricted time and space and money can be great indeed... Likewise, the food served in the IKEA canteen and many other canteens whose food I have enjoyed, takes advantage of innovations such as freezing and canning to provide a high volume of food with little wastage.

We dream of finding such places in the city. She names a few in London, but in practice they are rare, as rare as hen’s teeth. Instead, seats are for patrons only. And people squeezing by on a budget will bring their own food, hiding it, smuggling it in, buying a cup of tea to get somewhere to sit.

Hiding one’s body and one’s lack of money has become part of survival in London... Last summer a woman nervously approached me while I ate a cheeseburger in McDonalds near The British Library to ask for the tokens attached to my coffee cup so that she could get a free coffee and then I watched her fill it with as many free sachets of sugar as was required to achieve an intake of calories that might sustain her life for one more day.

An aside here in praise of the Burrell Collection building in Glasgow, which is located in a large public park. I visited this while away recently. It has a strong policy in favour of inclusivity and there is a large space near its reception area marked ‘picnic area’ which makes it clear that it is OK to bring in your own food and eat it. (There’s another picnic area upstairs as well).

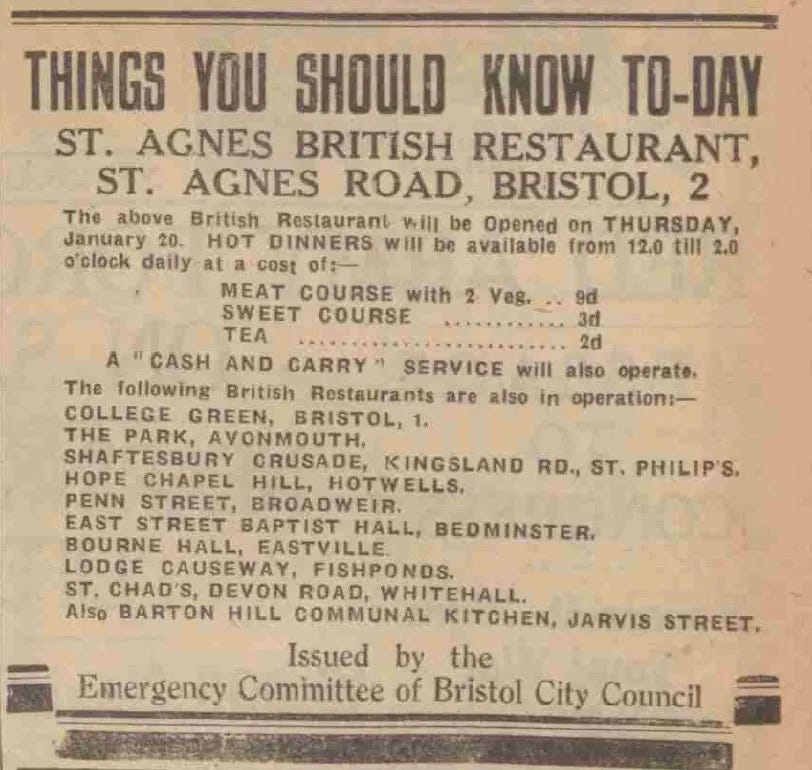

(Image: Western Daily Press, 12 January 1944. Via findmypast.co.uk)

When you describe all of this, it sounds like a utopian demand, but it turns out that canteens like this used to exist in Britain—the “British Restaurants”. Johnson is told about these by a security guard at the British Library that she ends up in conversation with:

She said that when rationing was going on and there wasn’t enough food during the war the government set up ‘British Restaurants’ to serve cheap hot food for everyone so that people had enough to eat, things like semolina and stew... the food wasn’t too bad and they were really cheap. She was very keen to tell me about the British Restaurants, very excited; she remembered them fondly. I tried to imagine a British Restaurant now, a government-backed scheme to make sure all comers were fed as a matter of the greatest national importance: I couldn’t.

British Restaurants were a wartime initiative, and extended after the war, some for quite a long time. She’d had this conversation because the guard had noticed her book, Slice of Life, The British Way of Eating Since 1945. The book more or less confirmed the security guard’s story:

British Restaurants served nutritionally balanced meals (according to contemporary science) and had libraries and fresh flowers on the tables and gramophones and pianos and felt as if I were reading about a utopian vision of the future like I would see in a science fiction film... Lord Woolton, the conservative minister for food, who had asked a socialist friend he knew to design the state-subsidised canteens, called them ‘one of the greatest social revolutions that has taken place in the industry of our country’.

Unsurprisingly, the canteens also produced improvements in the wellbeing of workers. Although they were popular, the government withdrew funding in 1947, although some lasted into the 1950s because councils took over running them.

Well, as the saying goes, the only new thing in the world is the history that you didn’t know:

The wartime memory of eating that has been encouraged to survive is of rationing, of lack, but for many people, there had never been so much hot, filling food. A seat, a table, a glass of water, a plate of food with the calorie density to sustain a life for a good while; the space and the time in which to unfold.

And as Johnson notes, almost the only place in London which has cheap subsidised canteens is the Houses of Parliament. It has ten of them.

2: The case for a land value tax

The long-serving Chief Economic Commentator of the Financial Times, Martin Wolf, became more radical after the global financial crisis, or more precisely, his economic views became more heterogenous. This shift has broadly remained in his thinking since then. All the same, I was surprised to see him advocate a land value tax in a column last week.

As far as I can tell, the article is behind a paywall, so I may include slightly more extracts than I might normally do.

The idea of Land Value Tax goes back to the 19th century, and the work of Henry George, but many 19th century economists agreed: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill and his son, John Stuart Mill. Since then, it has been taken up by different people, of very different political persuasion, without ever really being implemented anywhere.

There are obvious reasons why this is so:

Such a tax would be economically efficient and morally just. But it has been politically impossible: the landowning interest, which now includes a large part of the population as owner-occupiers, has been too strong.

However, he suggests, given the crisis in public finances in the UK and elsewhere, the politics might be changing.

(Oxfordshire Landscape, 1944, by Paul Nash. Via Rawpixels, CC BY 2.0)

Wolf traces part of the problem to the simplification of economics models in the later 19th century: rather than thinking about three factors of production (land, capital, and labour) this got simplified down to two (capital and labour) and land was tucked in with the capital.

Wolf references some 2022 US research that models the effects of a land value tax in the United States, and there’s a short version of this in VoxEU.

And it’s worth stripping out the different elements of the argument: moral, efficiency, incidence and impact.

The moral case for separating the return on natural resources from that on other assets is that the former pre-exist human efforts. Their value depends on the latter, but most definitely not on those of their owners.

Effectively as cities get richer, the land value increases, but only those who own the land capture this benefit. Public investments such as new transport links also produce returns to land that benefit its owners.

In terms of efficiency, we know where land is (and ought to know who owns it) whereas in a globalised world capital is slippery and workers do move around, partly in response to tax signals. (Although the argument about the slipperiness of capital is over-stated, generally, since to generate returns it has to touch the sides somewhere.)

And given the governments do need to find ways to increase revenues, “ideally in ways that do not reduce prosperity”:

socialising much of the yield on land is an obvious way to do this. Moreover, the tax base is huge: in the US and UK, the value of “non-produced assets” is more than half of total assets. The same is true in many other countries.

Of course, one of the benefits of taxing land is that you can also tax incomes and capital less. The US research suggests that the impact of this is significant:

The authors of the paper estimate from one simple model that an increase in the tax rate on the value of land from a level of 0.55 per cent to 5.55 per cent, with reductions in taxation of produced capital and labour of 28 and 10 percentage points, respectively, would raise output by 15 per cent relative to trend. If policymakers want to promote growth, this is an obvious place to start.

Land value tax would also, he suggests, address one of the problems in our current financial system, that much of the credit system simply finances investment in land rather than productive investment:

the credit system now mainly finances land ownership. In this way, rents on land are converted into interest on unproductive debt. Speculative bubbles in land also drive the credit cycle, to devastating macroeconomic effect.

The best single guide I found on Land Value Tax while doing my usual modest research was by the Scottish Land Commission. Perhaps this is not surprising, since land has been a huge political issue in Scotland since the Highland Clearances, and earlier.

Of course, there would need to be transitional arrangements. There would be some negotiation about whether one’s main home was excluded. But in general, the effects of Land Value Taxation would be beneficial, and ought also to have positive effects on the dysfunctional British housing market.

Wolf didn’t mention it, perhaps because of the FT’s international readership, but in the UK a Land Value Tax could work as a type of wealth tax, since 50% of land is owned by 1% of the population. (One of the letters in reply to Wolf’s article also pointed out that the Liberals had tried to pass Land Value Tax legislation in 1909, but had been blocked by the House of Lords, and Ramsay MacDonald’s 1931 Labour government had passed LVT legislation but it was never enacted.

I read some of the comments, which revealed two things to me. The first was that the land-owning interest remains strong—many of the comments came from landlords, for example. The second is that very few people had a clue what the land value tax proposition is—so the comments were also wildly uninformed.

It’s worth borrowing Graham Molitor’s policy S-curve model here. Emerging ideas have to go through a ‘framing’ stage which allows them to emerge, then move into an ‘advancing’ stage, where activists and advocates can cohere around a broadly shared set of principles about the idea might work, before arriving at the edge of the mainstream, where the ‘resolving’ stage kicks in.

Right now, I’d say that—given that, unlike, say, the idea of Universal Basic Service—the idea of Land Value Tax is hard to state clearly, and the existing research is unclear—that it’s still fumbling around in the Framing stage. Landowners will be able to sleep easily in their beds for a few years yet.

Update: Endings

I wrote about Dougald Hine’s new book ‘At Work in the Ruins’ on Saturday. It turns out that Richard Smith, who edits the medical journal The Lancet has written about the book in a striking column, which is outside of the paywall. Here’s an extract:

At Work in the Ruins has two powerful images that capture the fragility of modernity. One is the fish tank. Keeping cold water fish alive in a tank is a complex business: the water must be cleaned and changed, the electric filter maintained, and a chemistry kit used to test a dozen indicators. (As I read this, I thought of an intensive care unit.) A common consequence is dead fish, but a river or lake does it all “for free and with ease.” We live in a fish tank.

The other is the contrast between Israeli and Palestinian hens. The Israeli hen “cannot survive, grow, or produce eggs without special shots, a special mixture of food, a special mixture of food” and much technology. In contrast the Palestinian hen has adapted to the harsh environment over thousands of years. It doesn’t need the technology to keep producing eggs, although it seems likely that it produces fewer. But when the technology collapses the Israeli hen will die and the Palestinian hen survive. We are like the Israeli hens. (As far as I can tell, Hine is not making a political point by contrasting Israeli and Palestinian hens.)

j2t#424

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.