12 October 2022. Billionaires | Money

Billionaires are less smart than they think they are. // Defacing money down the years.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Billionaires are less smart than they think they are

Scott Galloway’s has been reading the text messages between Musk and pals revealed during the court process over whether or not Musk was going to have to buy Twitter after all. This is good because it means the rest of us don’t have to. He comes to some conclusions about the super-rich that are worth sharing here.

They’re not as smart as they pretend.

The logic, prose, and general discourse they reveal are astoundingly … unastounding. The wealthiest man in the world and his acolytes are, like the rest of us, unsophisticated, obtuse, and petty. Maybe more so. We thought billionaires were playing 3D chess while we played checkers. It turns out they’re playing the same game, but on a more expensive board.

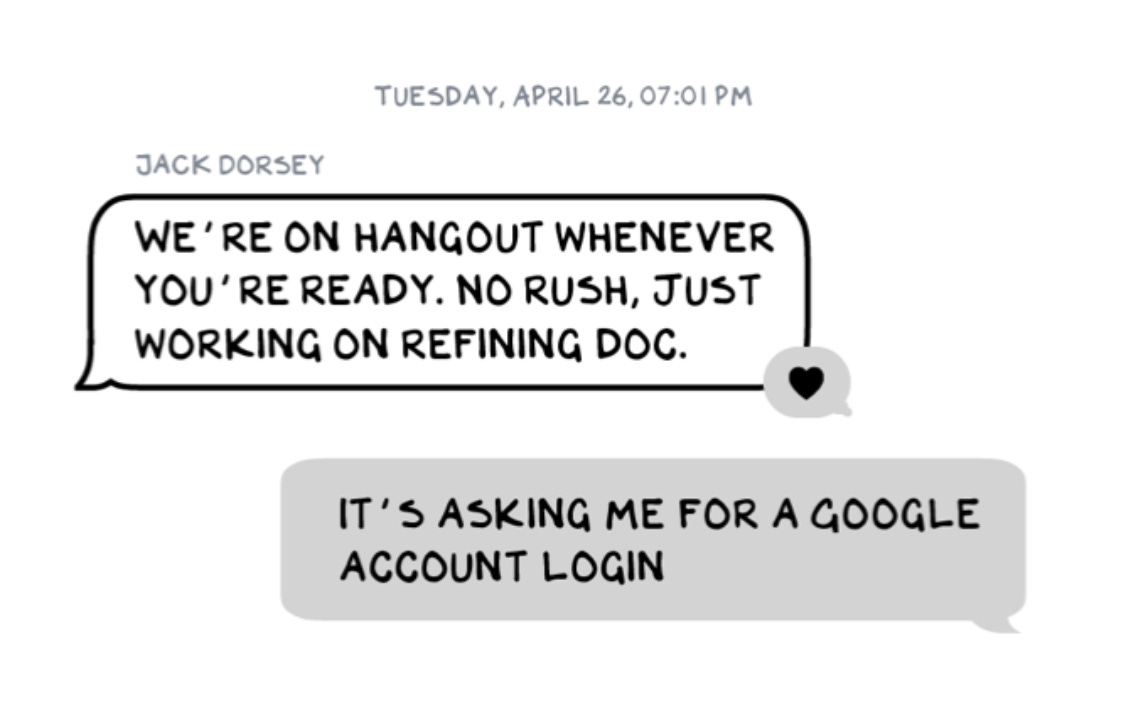

(All images via Scott Galloway)

They get confused by their technology, they try to get jobs for their kids, they can always do with a bit more money.

But there’s a lot of deference, and it’s all based on how much money you have.

As it happens Galloway’s take on this is that Musk doesn’t come out of all of this too badly (except, see below in a moment) but the people who are in his WhatsApp circle are simply terrible:

It appears our idolatry of innovators has seeped into the minds of the uber-wealthy, sickening them with an uncontrollable tendency to fellate the cool kid for a chance to sit at his table in the cafeteria... The undoing of many powerful people is that they enter a hermetically sealed bubble of fake friends.

But Musk doesn’t know how to deal with ordinary grown up behaviour.

In the whole document, 151 pages of it, Galloway found just one example of someone pushing back—from the Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal, who politely suggested, after Musk asked publicly ‘Is Twitter dying?’, that they could have a chat about this, that there was more going on than he knew about it. And Musk was just plain rude.

Here’s his tweet.

And here’s the exchange it led to:

The super rich are different from you and me. They have a lot more money.

When Musk is canvassing for investors to help him take Twitter private, Larry Ellison—who made billions from Oracle—offers to put up a billion dollars. Over a text.

This reminded me of the scene in Liar’s Poker where, in the ‘80s, one of the investment bankers says if we’re going to play we’ll play for real money. He ups the bet from $1,000 to $10,000. (This is on a game of chance based on the serial numbers of dollar bills.) At this level, money becomes a status play.

Galloway is more relaxed than I am about the super-wealthy, but he can’t help himself here: he finds it distasteful:

I believe it’s important to have incredibly successful people who are exponentially wealthier than the rest of us — it’s a bedrock principle of capitalism, creating an incentive structure that inspires productivity and prosperity. However, when people are offering billions over text to help out with another billionaire’s vanity project, in the same nation where 1 in 5 children live in food-insecure homes, then … isn’t America a bit fucked up?

There’s not that much difference in talent between the rich and the super-rich

Galloway has met them both, and he does believe that the rich tend to be smarter, more hard-working, better at building networks, than the rest of us. Your mileage might vary on this of course; you might think that in an era of low social mobility they just started with a better hand and cared more about making money than their contemporaries. Anyway, Galloway’s take is that the main difference between the rich and the super-rich is that the super-rich mistake luck for talent.

Going from millions to hundreds of millions or billions is less a function of incremental intelligence and more a function of timing. Proof? Elon’s text record…. (H)is mega-billions flow from a well regulated capital market, a web of enforceable contracts, the diligent labor of thousands of workers, and, not least, billions of dollars in government subsidies , including a timely $465 million DOE loan that enabled Tesla to produce the Model S. So, is Mr. Musk a genius or an impressive man whose skills were set against a unique moment and place in time?

Galloway observes that power tends to go to people’s heads. When you add it to money it becomes intoxicating.

Research shows power causes us to downplay potential risk, magnify potential rewards, and act more precipitously on our instincts. In other words, you lose your ability to self-regulate; you need others to do it for you... But Elon’s history of reckless, childish behavior and these texts prove there is no group or individual who is a truth-teller.

Of course, the rest of us have to live with the consequences of all this—because the super-rich also distort the landscape of everything that goes on around them, with little regard for the public costs. Galloway doesn’t mention the idea, but his piece is a strong argument for meaningful taxes on extreme wealth.

2: Defacing money

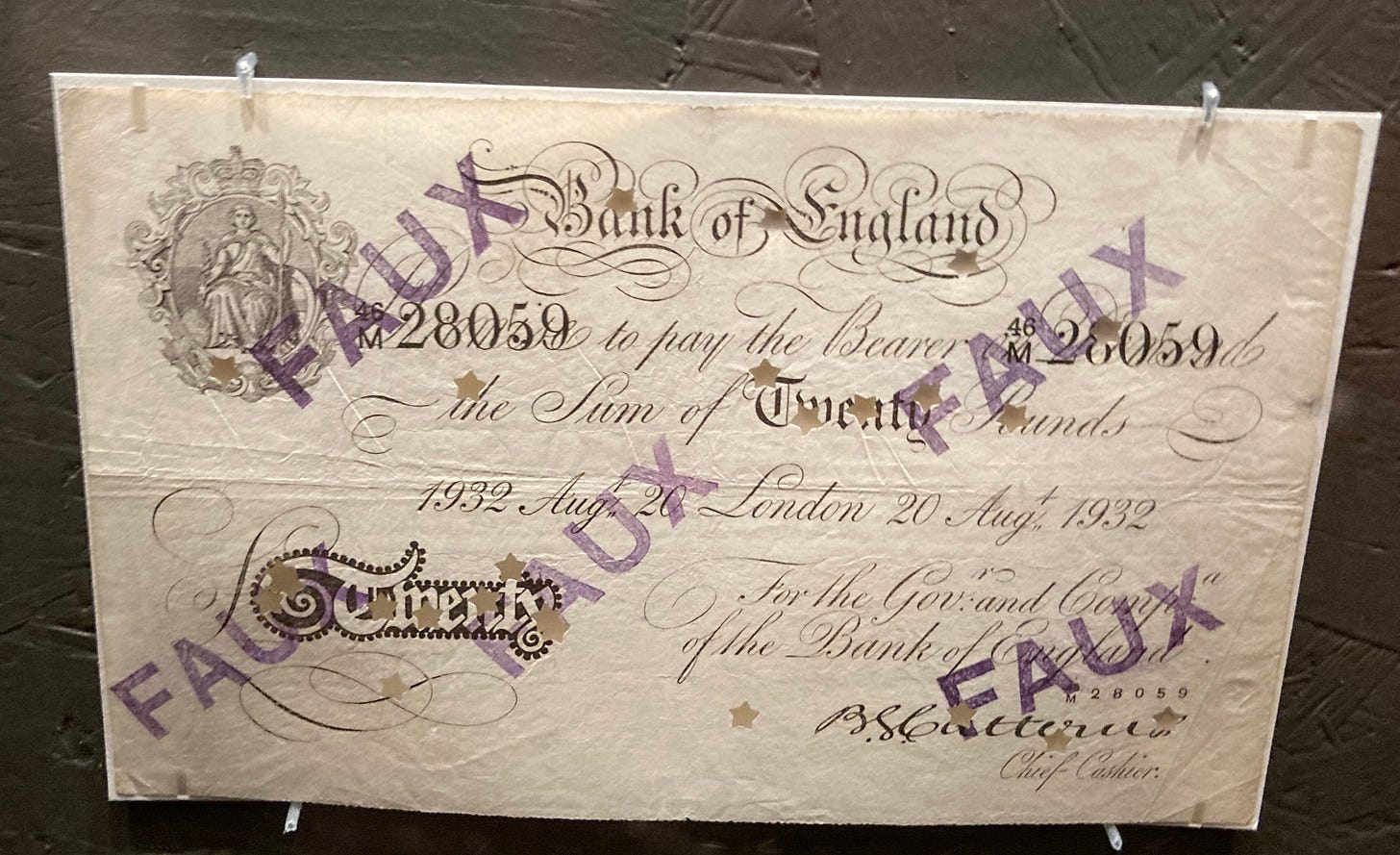

(All photos in this piece Andrew Curry/Fitzwilliam Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

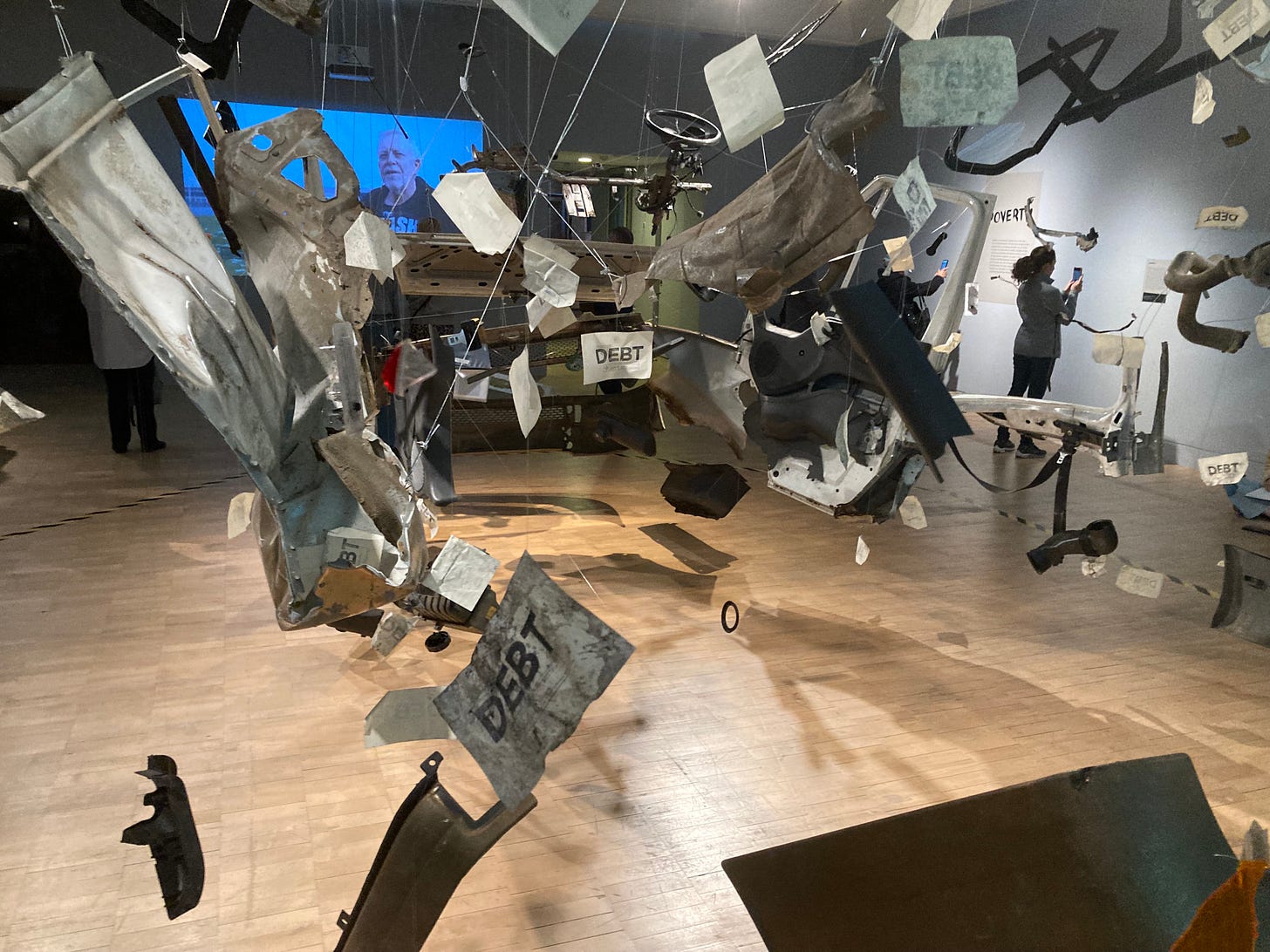

I was in Cambridge yesterday—more about that another time—and while I was there I managed to fit in a visit to the Defaced! exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum. It is about forms of protest that have involved defacing coins or notes. It turns out that this involves a lot of protest, in a lot of countries.

The first thing to say is: kudos to the curator who had the idea for this. The minute you start reading the exhibition boards, you realise how visceral much of this protest is—coins and notes, after all, go to the heart of the authority of the state. Defacing them or forging them is striking back at this. It also looks terrific: posters decorate the pillars at the front of the Museum, and the gallery space itself looks like the scene of a protest.

It may also be a form of protest that’s running out of road. A short video display at the end of the exhibition reminded us that only 8% of the world’s money is now in the form of coins and notes, and that the people who use them, instead of using digital forms of money, are largely the poor and the marginalised.

In this piece I’m just going to tell a few of the stories from the exhibition, with a few photos.

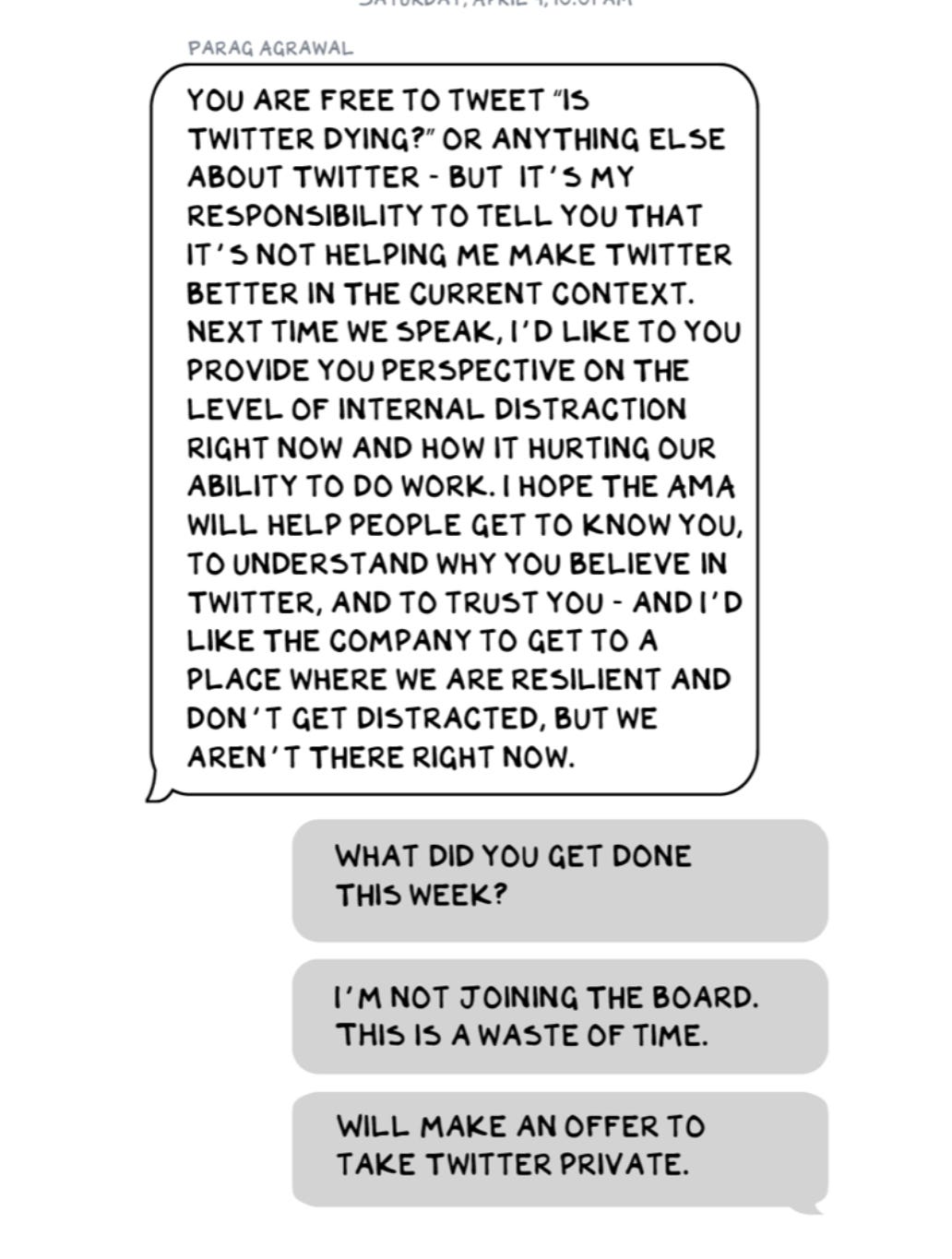

There’s a long history here. It goes back 250 years, and the first rooms cover all kinds of early protest. The murder of demonstrators at Peterloo in Manchester in 1816 was marked by coins with ‘Peterloo Murder’ stamped on them.

This was a form of protest that was hard to catch, at a time when the authorities could be brutal.

In 1800, with widespread hunger caused by price rises and profiteering, John Hancock produced a coin labelled ‘The Uncharitable Monopolizer’. Underneath: ‘Will starve the poor’.

The exhibition also has a long list of occupied countries where currency and coins have become a site of the struggle.

Making women visible. The number of women commemorated on bank notes is a small—just 15% worldwide. This artwork banknote (by Lady Muck) commemorates Che Guevara’s wife, Aleida March, who fought in the Cuban Revolution and brought up their four children as a single mother after his death in Bolivia.

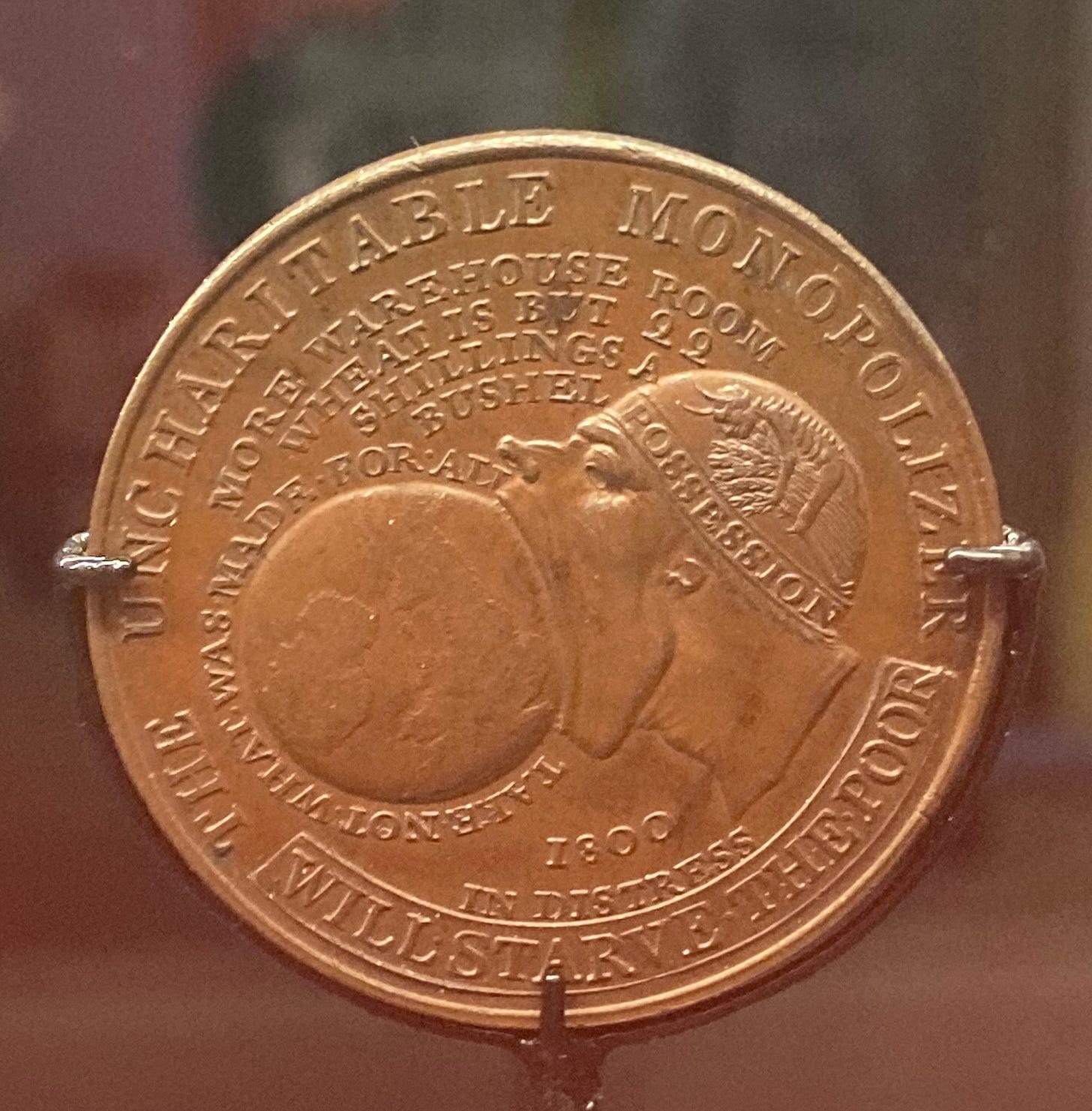

A truck full of debt. The exhibition had reconstructed the demolition of a Ford Transit truck by the artists Hilary Powell and Daniel Edelstyn, part of a bigger project:

they printed their own money, just like the Bank of England, except that they sold the bills as works of art. The duo splits £20,000 of the sales proceeds, donating half to local nonprofits and using the rest to buy payday-loan debts resold by banks (usually to collections agencies) for a fraction of its original value.

The notes celebrated local people in the Walthamstow.

The truck was filled with paper vouchers with the word ‘DEBT’ printed on them. This particular project has an afterlife. Metal from the truck was melted down into commemorative coins that were sold off-to buy more debt and cancel it.

Winning the war by killing the currency. One of the cunning schemes developed by the Germans during the war—Operation Bernhard—was to forge vast numbers of British banknotes to wreck the British economy. The forgers were Jewish engravers, artists, and typographers held in concentration camps who were assembled at Sachsenhausen. (There’s more on this on Wikipedia). They produced between £100,000,000 and £300,000,000 worth of notes, many of which were never identified, in the days when a million English pounds was still worth something. Because they were high value prisoners many of the forgers survived the camp.

One of the cards in the exhibition tells the story of Adolf Burger, a typographer sent to the camps after being arrested for forging baptismal certificates for Jews. He survived the war but said that the forgers thought of themselves as ‘dead men on holiday’.

Monopoly money. Inevitably there’s some modified Monopoly on display. In 2020, the artist Penny overprinted a $2 bill with the phrase ‘Monopoly on Vioence’, thereby at a stroke making a witty point about the underlying nature of state power.

And while we’re on the politics of crisis, the British artist Wefail has issued a series of bank notes to commemorate leading British political figures. The £5 Theresa May note reads, ‘What’s Yours in Ours’; the £10 Rees-Mogg says ‘Nanny and I will be fine; the £20 Johnson, ‘We Own You’, and the £50 Marget Thatcher, ‘Eat The Poor’. Full circle, perhaps.

The ‘Defaced!’ Exhibition is on at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 8th January 2023. Entry is free, but you need a ticket.

j2t#380

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.