12 November 2021. Memory | Tokyo

The persistence of memory, often against the odds. Views of Tokyo.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The persistence of memory

A guest post by Peter Curry

I’m drawing here heavily on the work of Thomas Verny, a psychiatric researcher into forms of memory.

He grew interested in the topic when he stumbled across the Onion-esque headline: Tiny brain no obstacle to French civil servant. Insert your political figure of choice in place of 'French civil servant'.

The takeaway is that huge chunks of the brain can go missing and yet the brain can continue to function. The brain is very adaptive in response to exogenous or endogenous shock (there are debates as to how adaptive it is).

Sadly, we can't really run experiments where we remove parts of the brains of French children at birth and then give them jobs at the Quai d'Orsay to see how they do (bloody ethics committees), but fortunately, plenty of animals and insects go through massive changes to the brain as part of their natural life cycle.

Verny focuses specifically on cellular memory. The memories of many different animals persist in circumstances which would suggest that they should persist. For instance, planarians are regenerative worms. If you chop up planarians into lots of different pieces, they will grow back to nearly their full size, thanks to a resident population of stem cells (neoblasts). And yet, they continue to retain memory if you do this.

One study involved acclimatising worms to two environments - rough-floored and smooth-floored. Worms naturally avoid light, so when food was placed in an illuminated, rough-floored zone, they didn't go for it immediately. But the rough-floored worms were quicker to go towards the food than the smooth-floored worms. Then the researchers chopped up the worms.

After they'd regenerated, the previously rough-floored worms were then slightly faster to go for the (rough-floored) food than other worms. Interestingly, they didn't do this until their brains had regenerated fully, so clearly the brain of the planaria holds some mechanism for integrating or utilising these memories.

This happens across different species. Bats are thought to have similar neuroprotective mechanisms that help them retain information through hibernation. When arctic ground squirrels hibernate, autophagic (self-eating) processes rid the squirrel's body of anything extraneous to survival, including (RIP) their gonads. Much of the brain disappears, including much of the squirrel's hippocampus, the part of the brain often associated with long-term memory.

And yet, in the spring, they are still able to recognise their kin and remember some trained tasks. Hibernating groups don't do as well at remembering things as control groups who didn't hibernate, but this isn't really a surprise. Also, the squirrels gonads do grow back (hurray!).

There are a lot of different results in different squirrel, marmot and shrew studies (all of which seem to happen in Germany, so if you have a pet rodent I wouldn't take it on your next holiday to Munich) which mostly conclude that these animals can remember things when they return from hibernation.

In insects, similar things happen. Insects, like humans, go through a radical reworking of the brain throughout their life-span. The insect life process runs something like egg - larva - pupa - imago - adult, varying wildly for whichever insect you've managed to trap in your laboratory.

Researchers worked on a species called the tobacco hornworm, and linked a shock with the smell of ethyl acetate (EA). If the larva was exposed to the shock and EA, as a caterpillar, it would try to move away from EA towards fresh air environments. So the learned response is surviving the restructuring of the caterpillar's brain (tobacco hornworms have about 1 million neurons - you have about 100 times this many neurons in your gut alone).

And Verny stops off finally, with you. Humans go through a total reconstruction of themselves as they grow to adulthood. Neuroscience researchers are fond of saying things like, "your cortical thickness only decreases as you age". (Also worringly, it may decline more steeply in children of lower socioeconomic status.)

And yet, much of our functionality seems to get better and more coherent as we get older, and we continue to retain memories.

Verny doesn't discuss this, but to make things more complicated, plants also 'remember' things, such as the timing of the last frost.

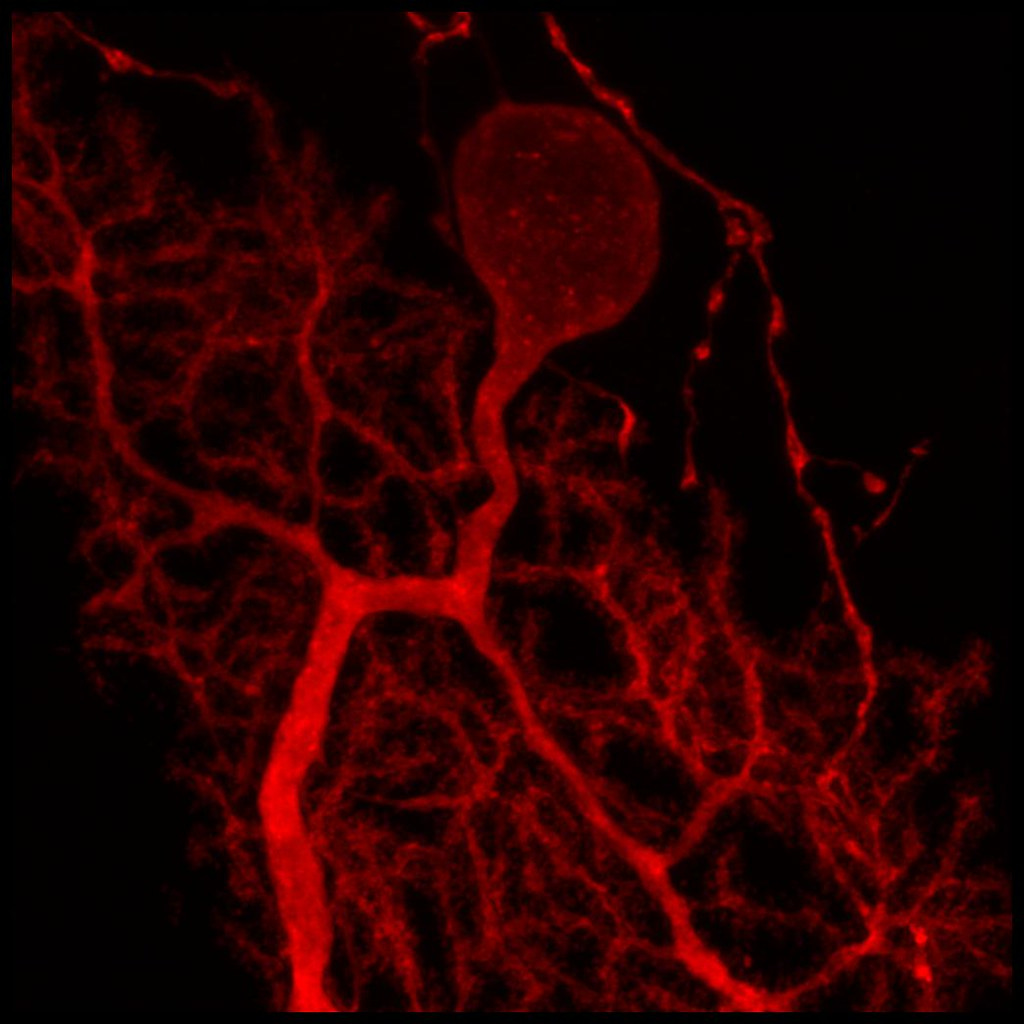

Verny's conclusion is that 'memory', as we understand it, must be partially encoded throughout the body. Indeed, if long-term potentiation, the strengthening of synapses based on patterns of activity, is one of the most important ways in which memory is stored, then how can it not be? I may have misinterpreted this, but it seems part of the problem here is that we are still emerging from the era of fMRI scanning when researchers basically tried to functionally localise all brain regions (the hippocampus does memory, the amygdala does fear, etc.).

This is not how any of these regions work; barring edge cases, they mostly seem to deploy a network of brain states in response to a problem. In the functional localiser era, saying that memory is distributed is problematic, but we're very swiftly moving past that to more complex networked understanding of the brain. Verny seems to be tip-toeing throughout this article to avoid the wrath of memory researchers.

And he could go further - the study of memory has focused for a long time on the hippocampus (and more recently the neocortex). But motor memory is mediated somewhere in the cerebellum, a terrifying, mostly uncharted brain region that neuroscientists are afraid to say the name of five times while looking into a mirror.

Part of the problem is that ‘memory’ here is clearly a heavily overloaded term. Different types of memory may be biologically very disparate, and categorising them as ‘memory’ may be holding us back. Clearly memory networks are diverse, disparate and confusing as hell, and understanding them is going to be a long process.

Thomas Verny’s book is here.

This post is cross-posted from Peter’s Substack newsletter.

#2: Views of Tokyo

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has an exhibition looking at the art celebrating Tokyo over the last 250 years. It opened in October, and runs to January, and is reviewed in Apollo magazine.

The review, Tim Smith-Laing, notes that historically Tokyo has been ‘an historically unlucky city in many ways’ but was blessed, at least in having Hiroshige record it in the mid-19th century, just before it was renamed as Tokyo (‘Eastern Capital’) following the Meiji Restoration.

Hiroshige’s ‘One Hundred Famous Views’ captured the city in 1859, just as the country opened up to the outside world after 200 years of isolationism—a period of rapid social, cultural and technological change. Although Hiroshige built on an existing tradition of depicting famous places, his pictures themselves perhaps reflect this atmosphere of change; Smith-Laing notes their formal innovation and radicalism.

(The Suijin Woods and Massaki on the Sumida River, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856), Hiroshige.)

Tokyo’s bad luck might include the vast earthquakes of 1855 and 1923: the second killed 100,000 and left two million homeless. The devastating incendiary bombing of the city in 1945 compares to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and prompted an elegiac series of images by Koshiro Onchi, ‘Scenes of Lost Tokyo’, which are perhaps a counterpart to Hiroshige.

(Tokyo Station, from the series Scenes of Lost Tokyo (1945), Koshiro Onchi. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. © the artist.)

But cities survive and recover. Part of the exhibition brings the story up to the present day, with the energy and strangeness, still, of the 21st city.

(Tokyo from Utsurundesu series (2018–present), Mika Ninagawa. Courtesy the artist and Tomio Koyama Gallery; © Mika Ninagawa.)

The Ashmolean has made a busy trailer for the exhibition.

j2t#206

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.