12 June 2023. Politics | Growth

Why we choose narcissists as leaders. // ‘Beyond growth’ moves towards the mainstream

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Why we choose narcissists as leaders

The sight of Trump being charged in the US, and Johnson choosing to disgrace himself on the UK before a House of Commons Committee did it before him, all within a 24 hour news cycle, was almost too good to be true. Especially since the two men had been touring together recently, perhaps exchanging tips and tricks.

Maybe God is a wannabee scriptwriter, even if this was probably an early draft.

Given that both men got to benefit so richly from populism’s breaking wave in 2016, the timing also has something about it, as if the seven year periods that crop up in myth and folklore have areal meaning to it.

(Meme found online. If you are the creator, please let me know and I’ll credit you)

But that’s not what I want to write about here. Both Trump and Johnson are notorious narcissists, and I am wondering what it is about our current politics that means that the qualities of narcissism are so rewarded by the electorate.

I’m not the first person to have this thought, and in this two-part piece I’m going to do a quick canter through some of the research.

Since this is a two-part post, let me pull the threads of the discussion together before I get into the detail:

There has been an increase in narcissism in Western societies over several decades, which seems to be linked to greater individualism;

narcissists (especially grandiose narcissists) are more likely to be selected as leaders—in business at least—because they look like leaders, and then wreck the organisations they lead;

narcissists are more likely to be involved in political activity than non-narcissists, and also less likely to value democracy;

But it is still not clear whether this is a continuing trend or one that has passed its peak.

The first thing to say is that narcissism is the shadow side of self-esteem, and generally we think of self-esteem as being a good thing. One 2018 paper notes that “the endorsement rate” among adolescents of the statement “I am an important person” climbed from 12% in 1963 to 77-80% in 1992.

Self-esteem is also increasing in the Western world:

Middle school students from the United States had markedly higher self-esteem scores in the mid-2000s compared with the late 1980s.

So it’s probably worth separating out the two at the start:

Narcissism and high self-esteem both include positive self-evaluations, but the entitlement, exploitation, sense of superiority, and negative evaluation of others that are associated with narcissism are not necessarily observed in individuals with high self-esteem.

There’s also a distinction in the literature between ’grandiose’ and ‘vulnerable’ narcissism. The two overlap.‘Vulnerable’ tends to be associated with a “characterized by anxiety, a fragile self-concept, and low self-esteem“. Grandiose, in contrast, is

a more assertive and extraverted form characterized by high self-esteem, a sense of personal superiority and entitlement, overconfidence, a willingness to exploit others for self-gain, and hostility and aggression when challenged.

There are also measures of narcissism in the literature, assessed in the US by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory NPI), which measures for “self-reported grandiose narcissism” and this shows a 30% increase in grandiose narcissism between 1979 and 2006.

There are some problems with the NPI, but this finding seems to be borne out by other measures. And in terms of politics and business, we’re more interested in grandiose narcissism than vulnerable narcissism (although Trump appears to lurch between both).

The psychology literature is generally more interested in all of this at the level of social effects. The business literature is more interested in leaders and their effects. A paper from Charles O’Reilly and Nicholas Hall more or less summarises these in its title:

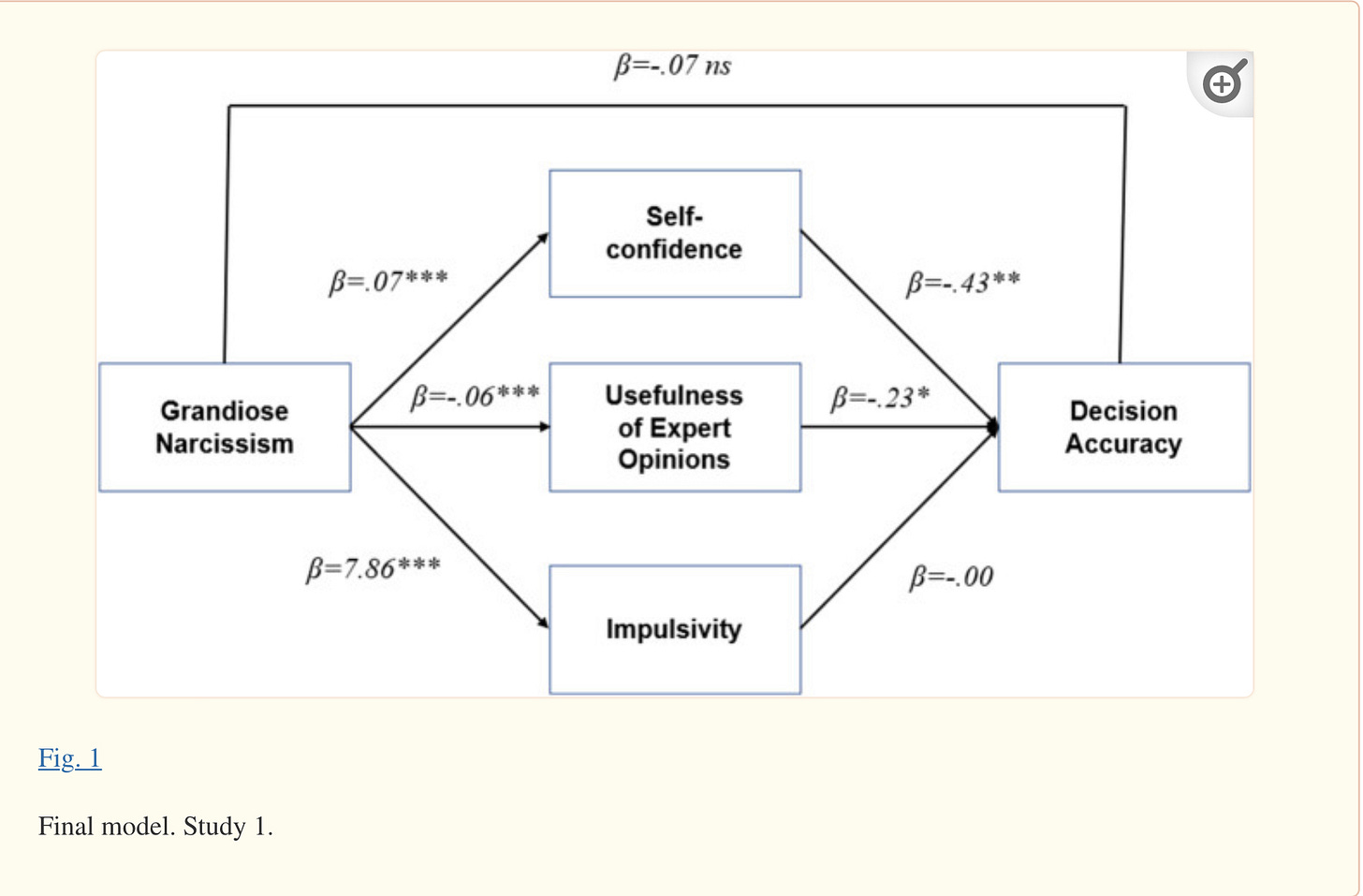

Grandiose narcissists and decision making: Impulsive, overconfident, and skeptical of experts–but seldom in doubt.

The article explores these three characteristics in more detail, by testing a set of hypotheses about the behaviour involved. The results of this model leads to a diagram that is also summarised in the text:

(Source: O’Reilly and Hall, 2021)

These attributes, which, in part, define grandiose narcissism, were, in turn, associated with the probability of making a poor decision (Fig. 1 ). Respondents who were more confident and saw experts as less useful were also more likely than those lower on these dimensions to make an incorrect choice. It was not narcissism per se that led to the increased probability of making an incorrect choice but the effects of narcissism on how respondents accessed information. Having made an incorrect decision, narcissists were also shown to be more likely to externalize the blame for their decision and to remain confident even after having made an incorrect choice.

It goes beyond “incorrect choice”, however, to a whole leadership style:

(O)nce in positions of authority, grandiose narcissists have also been found to make riskier decisions and jeopardize their institutions (O'Reilly & Chatman, 2020)... These tendencies make them potentially dangerous as leaders when their decisions can affect the lives and livelihoods of others.

An article at Stanford Business by Lee Simmons, which draws more widely on O’Reilly’s work, argues that one of the reasons why ‘grandiose narcissists’ are able to get into leadership positions is because they look like the type of people associated with leadership in modern organisations, notably because of their (over) confidence and willingness to be decisive. But—and of course there’s a but:

“They believe they’re superior and thus not subject to the same rules and norms. Studies show they’re more likely to act dishonestly to achieve their ends. They know they’re lying, and it doesn’t bother them. They don’t feel shame.” They are also often reckless in the pursuit of glory — sometimes successfully, but often with dire consequences.

All the same, O’Reilly and Chatman paper referenced above also makes a distinction between “abusive jerks” and “grandiose narcissists”. The former might still have a vision of the future that extends beyond themselves and so isn’t purely self-serving (think: Steve Jobs).

It seems that venture capitalists, in particular, are prone to choosing grandiose narcissists as leaders, which suddenly casts an insight into some of the behaviours of Silicon Valley start-ups over the years. And there are studies that show that when groups are set tasks in experimental settings, they are more likely to choose the grandiose narcissists in their ranks as leaders.

This last observation links to a clue about the circumstances in which such leaders emerge, again from the Lee Simmonds article:

O’Reilly thinks we may especially tend to choose narcissistic leaders in times of turmoil. “In the last few decades, big companies like automakers and banks have been threatened by technological disruption. So you could imagine that in anxious times people are looking for a hero, a confident person who says, ‘I have a solution.’” They may be the only ones who are confident in such times.

Anxious times. In a slightly sprawling piece in Unherd, Tom McTague reminds us that the ‘end of history’ decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union was supposed to be about the end of ideology and the rise of managerialism. But that wasn’t how it turned out:

Yet this world gave us the Iraq war, the 2008 financial crisis, the implosion of the Arab world, mass, unexpected immigration, austerity and eventually Brexit. After 2016, Johnson rose to prominence mocking the egos of the establishment that presided over this mess, eventually grabbing power at the height of its failure. His opportunity came because of the failures of the political class at home and abroad.

Of course, Johnson contributed to making this chaos worse, when he plumped for Brexit. But Brexit, certainly, was the classic narcissist’s ‘solution’.

In part 2, on Wednesday, I will look at the social and political research on narcissism.

2: ‘Beyond growth’ moves towards the mainstream

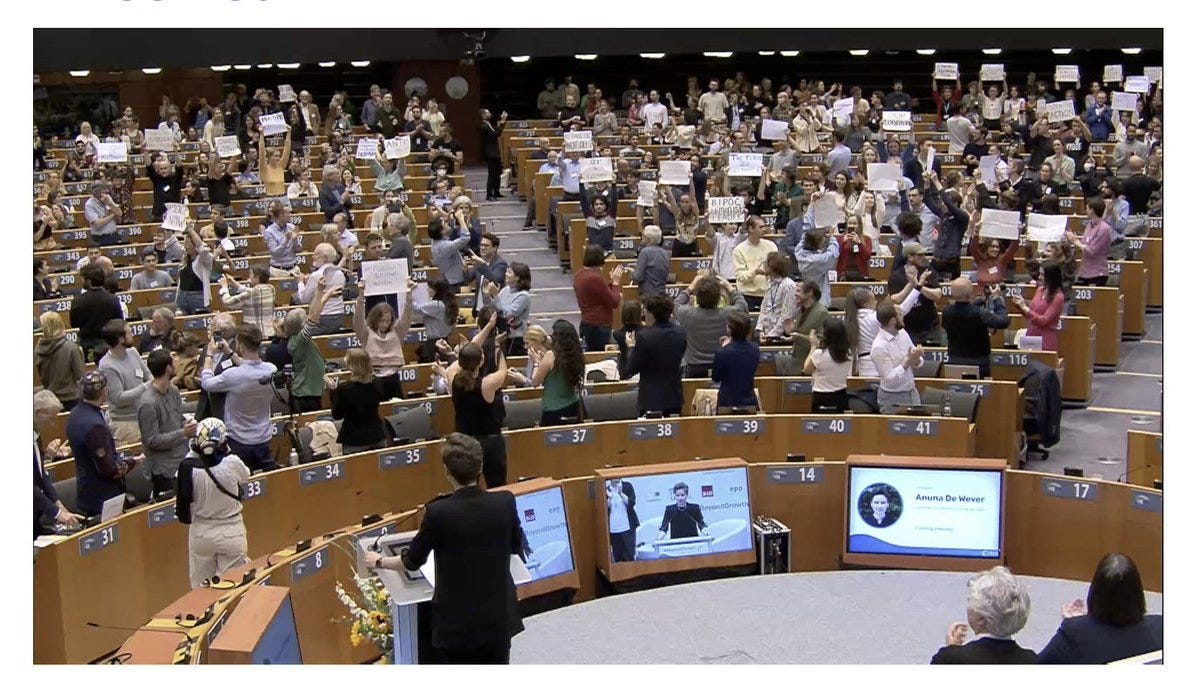

I noticed a rather nice piece of visual recording online of an EU Parliament conference on the theme of “beyond growth”, that I thought was also worth sharing here.

(European Parliament. Beyond Growth. Image: Visual sense-making.eu)

Over on the left, it looks like the familiar argument about the limits of GDP is being set up. In the middle, Kate Raworth’s ‘doughnut economics’ model gets a run out, and below it, there’s a discussion on wellbeing. Over to the right, it looks like there’s a discussion about the importance of measuring different and better things, and also a suggestion that citizens need to be closer to the heart of all of this.

I found this visual in a long Twitter thread by Julia Steinberger, who had attended the three-day event. (I wrote about an article by Julia Steinberger on Just Two Things this time last year). It looks like a typical EU event, with lots of speakers and plenaries, and you can see what they said online by clicking through on the different speakers. If you follow this area, even casually, you’ll definitely see people you know in the speakers’ roster.

This was Steinberger’s summary of what she enjoyed about it:

Topics covered planetary boundaries, trade, finance, fiscal policy, global South, decolonisation, gender, justice, well-being, social policies. Every panel included major advances in understanding. Together, the conference represents a monumental coming of age of post-growth. Being part of this event was a privilege and an honour. I wish I could share with you what being in such a space opens up in terms of determination to collaborate for a liveable world. The sheer electric energy of being in a room with so many young, critical, dedicated humans.

(Source:: EU)

It’s the second conference on this theme: the first was five years ago.

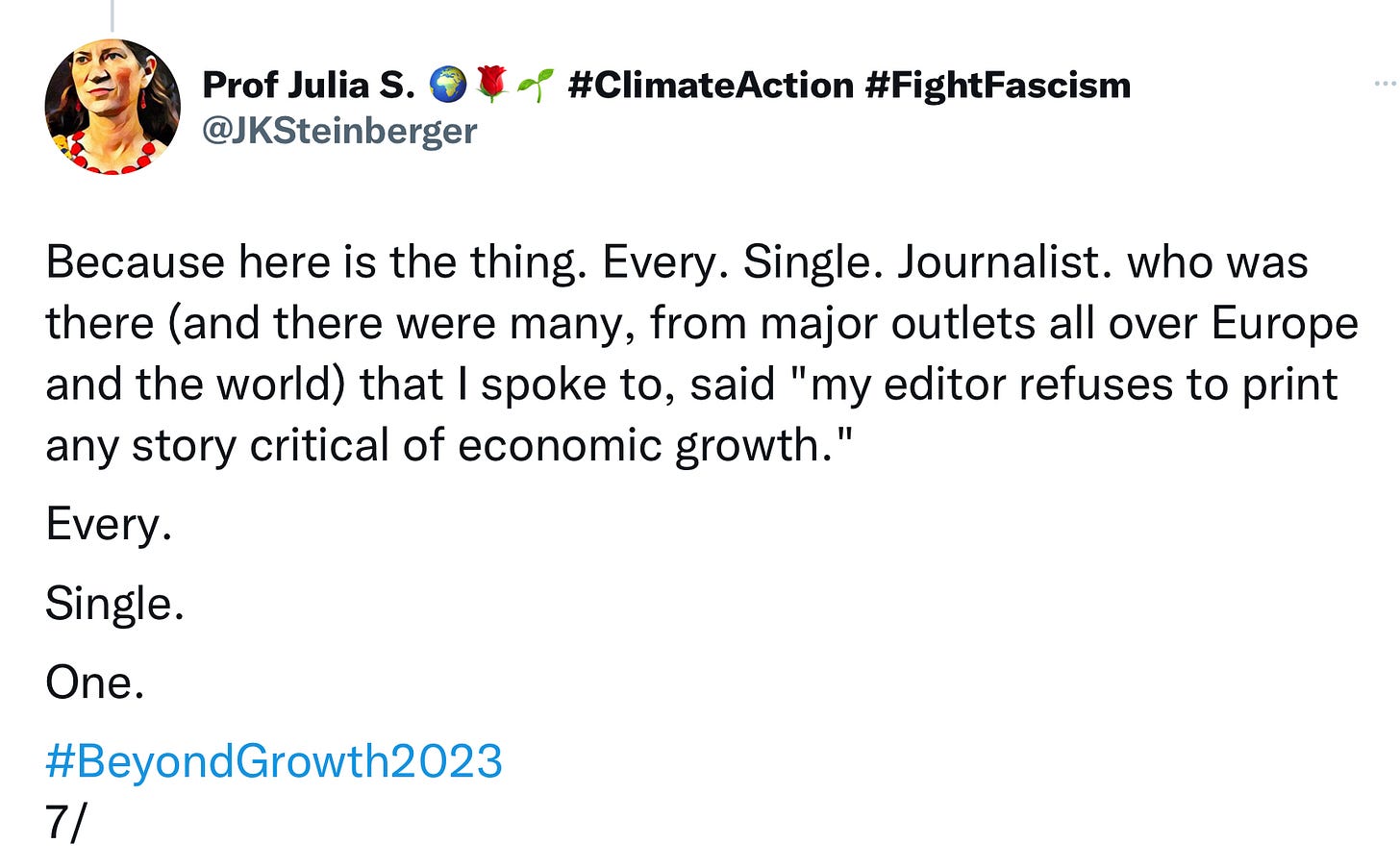

Steinberger headlined her thread by saying that despite the scale of the event, and its EU Parliamentary sponsorship, it hadn’t been covered by a single news organisation, and she came back to that point later on:

Source: https://twitter.com/jksteinberger/status/1659429919628165120?s=61&t=9tZ-KB3QE3gPzyt_XwFqEg

As a former journalist who is often enough critical of the bias of media outlets, this seemed unlikely, although there are other tweets on the #BeyondGrowth2023 hashtag that make a similar point.

Maybe it was true when she wrote it, but it’s not true now, since the Financial Times published a piece by Martin Sandbhu. Unusually, it’s not behind their paywall, so you can judge for yourself, but given that the FT is the paper of record for European capital it seemed to me to be a pretty fair-minded account. The headline:

'Degrowth’ starts to move in from Europe’s policy fringes.

I’ll pull out a couple of paragraphs:

Philippe Lamberts, a Green MEP behind both events, says he faced “quite a lot of pushback from the European Commission” the first time around. The attitude then, he says, was “if I didn’t believe in growth, I should find another job”. Five years on, it is a different story. Now “the big shots” — leading EU officials — “are playing ball” and engaging with the debate, says Lamberts.

This time, Ursula von Leyen, the Commission President turned out, along with some commissioners, the European parliament president Roberta Metsola, and Frank Elderson, from the executive board of the European Central Bank. von Leyen, in fact, told the event that “a growth model centred on fossil fuels is simply obsolete”.

Sandbhu notes some subtle—and perhaps necessary—repositioning by critics of growth, including by Lamberts:

It may help that the MEP does not, in fact, call outright for an end to growth. The conference materials studiously avoided the word “degrowth”. Lamberts says he prefers to speak of “shared prosperity within planetary boundaries”. He argues that we should debate what economic developments are consistent with this and act accordingly — “discussing these things is no longer seen as sacrilege”.

Sandbhu walks us through some of the positions here—from Dieter Helms’ argument that technology will continue to enable growth, to the scienctists in Nature last year who called on wealthy economies to abandon GDP as a policy goal.

His perspective that the event itself marks a move “from the fringes of Europe’s policy debate to at least being granted a hearing in the EU institutions”, of course, could come out of an emerging issues analysis paper. We are also seeing language about degrowth in IPCC papers.

And he also notes that the lessons from last year, in which the EU reduced natural gas consumption by more than 20%, without substituting oil and coal, while maintaining similar levels of industrial production, could play out on either side of the debate he delineates. However:

The experience of 2022, in other words, showed that large cuts in energy use and emissions are possible with concerted political action... What is certain is that the past year will have changed expectations about what policy action can achieve.

j2t#465

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.