Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

One of the results of the pandemic, apparently, has been a boom in automated chefs in India, according to a story in Rest of World by Varsha Bansal. It’s coupled with a sharp and continuing increase in food delivery services, a consequent increase in ‘ghost’ or ‘dark kitchens’, and has perhaps been accelerated by the shortage of labour during the pandemic, as people deserted the cities for their home villages.

Traditionally it’s been thought that Indian food is too complex, or too subtle, to be made by machines. But apparently not:

The parathas were crisped and dropped on a plate by a flat bread maker. Falafels and fries placed in a motorized basket were automatically descended into perfect-temperature oil in a smart fryer, and an impinger oven pushed out hot pizzas. Once done, a quality control manager measured the food’s weight and temperature. The result: a perfectly packaged box of hot food made within 12 minutes of receiving the order. “It’s the only way a rider would be able to deliver the food within 30 minutes of it being ordered” to meet the company’s promised delivery time.

It’s a sharp contrast from the traditional Indian street foods, but it also speaks to a change in Indian attitudes to food, at least among “a class of Indians who value service and convenience.”

(Flippy Robot on a Rail. Image: Mukanda Foods)

There is a raft of companies now competing in this space, some offering different types of machines that doing different things in the kitchen. Bansal’s description of some of these, made by Makunda Foods, made me smile:

There’s the Dosamatic, which can make one savory rice-and-lentil crêpe per minute; the Wokie, which simulates the constant movement of a chef cooking on a wok; the RiCo, a rice and noodle cooker, and the Biryani Bot. The machines are not humanoid — none have robotic arms or hands — but rather small-scale industrial equipment that handles repetitive tasks like tossing and stirring, freeing up that time for a kitchen staff to double up on other tasks.

Makunda insists that the machines are designed to help the chef, not to replace them. But they’re essential to making the economics of ghost or ‘cloud’ kitchens work, given the need for volume and speed. Rebel Foods, the oldest cloud kitchen operators in India, started in the restaurant business but moved to cloud kitchens because rents were too high. Automation does help reduce preparation times, but it’s not just about speed or cost:

“It’s more about having better control and consistency of the product,” said Joshi. “Every single time, the product comes out with the exact same consistency.”

Nonetheless, there are still questions about whether automation will stick. Labour is still cheap in India, sometimes as little as $1.70 per hour, so the business case for a machine that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars is hard to make.

Indian culture also values freshly cooked food, in the home and outside of it. There are fewer kitchen appliances even in affluent Indian homes. Chefs are often the most sceptical viewers of the machinery.

But culture may be changing. That fresh food is—in a patriarchal society—based on large quantities of women’s labour, often hours per day. And the signs are that Indian women are getting fed up with so much domestic labour, as seen from an uptick in the market for home chef equipment.

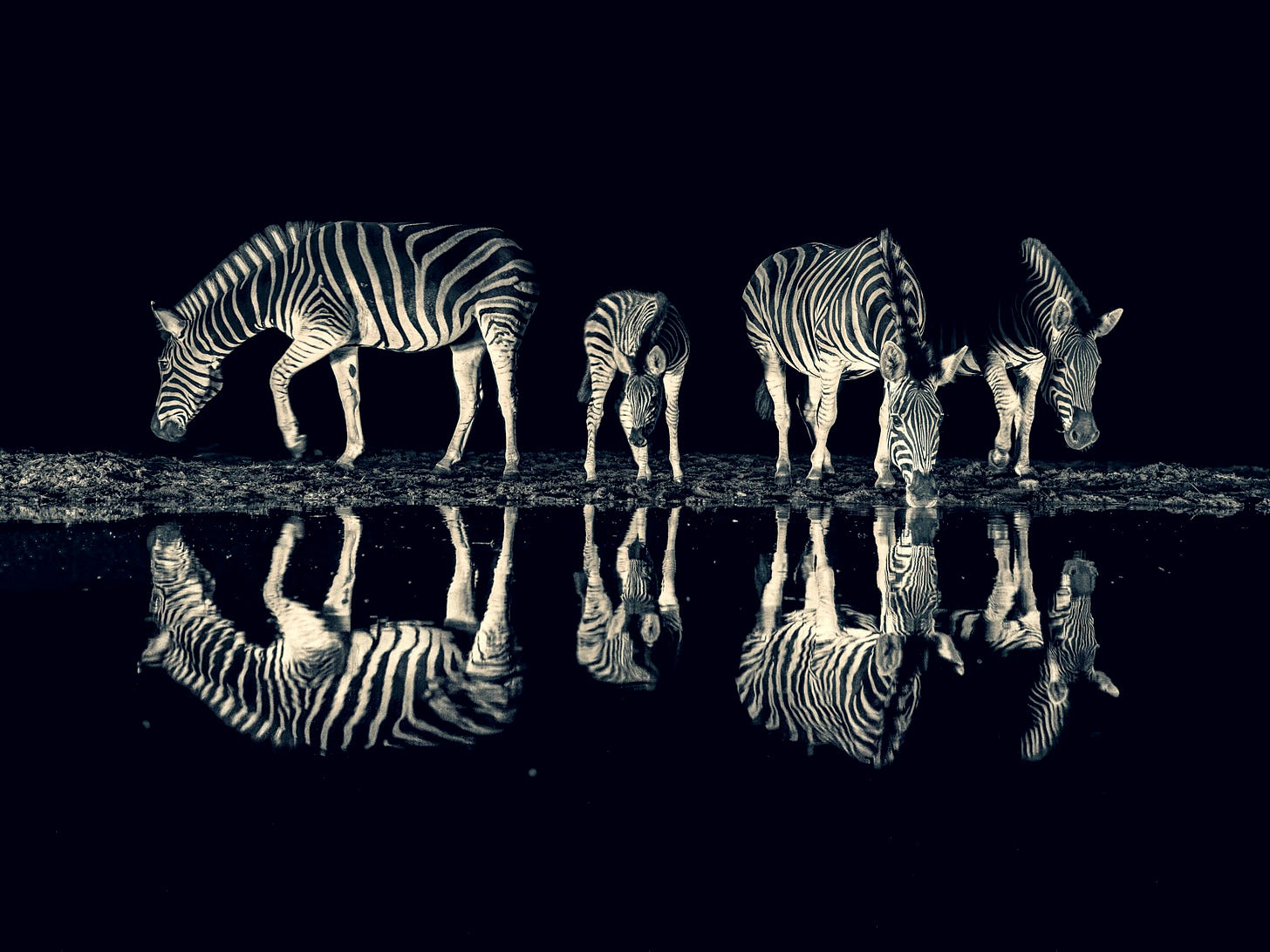

Jeremy William’s excellent blog alerted me to the environmental photography competition run by the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation.

The exhibits come in three categories—Incredible wildlife, Wildlife in crisis, and Reasons for hope—although the photos in each category seem to have become jumbled up in the overall online display. (I’m sure they would have benefitted from three online ‘rooms’, one per category. But that’s enough of the curating tips.)

The international photography competition is a new venture for the Foundation, to mark its 15th anniversary. The reasons why they have opted for the environmental theme are pretty obvious, but I’ll let them spell them out:

The choice of theme for this first edition is significant, reflecting one of the fundamental lessons to be learned when we come out of the current global crisis: that humankind’s future is closely tied to the future of the species we coexist with on Earth. Because there can be no future in a devastated, deserted and polluted world that has lost its biodiversity.

There are some stunning images here, and some desperate ones (because of the ‘Wildlife in crisis’ theme.) I recommend that you go and visit the online exhibition. But here’s one image to get you started.

(C) Jane Dagnall/ via Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation.

I’m away next week so Just Two Things will need to take a break. It will be back on 21st June.

j2t#116

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.