11 August 2022. Biodiversity | Inflation, again

Visualising our loss of biodiversity // Inflation and the unravelling of low-interest economics

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: Visualising our loss of biodiversity

The crisis in biodiversity is at least as serious as the climate crisis, and the two are obviously tightly connected, but the climate crisis gets eight times as much coverage as the biodiversity crisis.

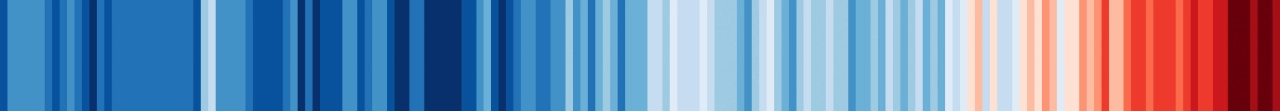

One of the reasons for this is that it’s easier to visualise the climate crisis—partly as a result of Ed Hawkins’ work creating the ‘climate stripes’, downloaded a million times in the first week of publication.

(Global Climate Stripes, 1850-2021. Data Source UK Met Office CC BY 4.0)

Miles Richardson has taken up the challenge of doing something similar for biodiversity—with support and encouragement from Hawkins—and he writes about his biodiversity stripes on his blog, Finding Nature.

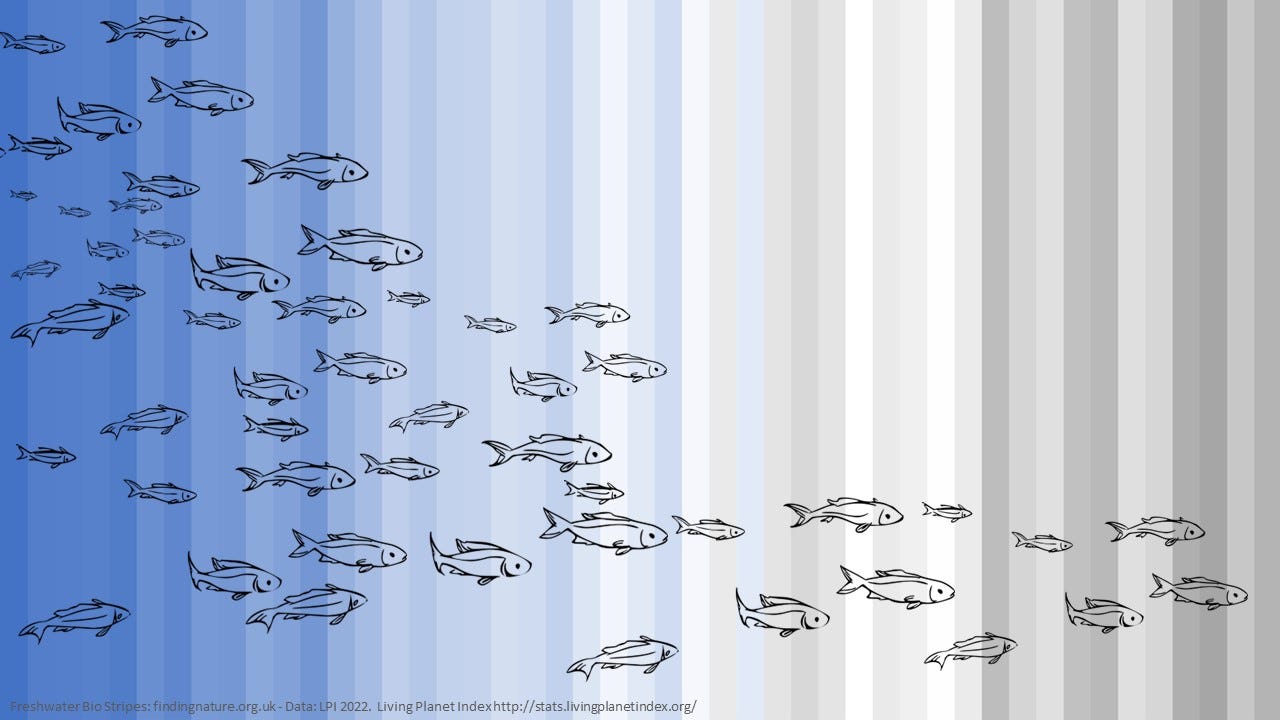

Using data from the Living Planet Index, he’s built a sequence that goes from green to grey (which sounds like it could be a country song). It looks like this:

(Global Bio Stripes – Data: Living Planet Index. Source: Miles Richardson.)

The good thing about the Living Planet Index is that it includes global data on more than 20,000 populations of over 4,000 species. But since it’s also a single number that captures such a large data set, when you reduce it to a colour sequence it really just fades from ‘OK’ to ‘a lot worse’:

(T)he colour changes would be too subtle for stripes to emerge. So, to capture the trend while providing stripes I simply created a random point between the high and low confidence intervals for each year. As for the colours, the decline of wildlife is a loss of vibrancy and colour, the green becomes grey.

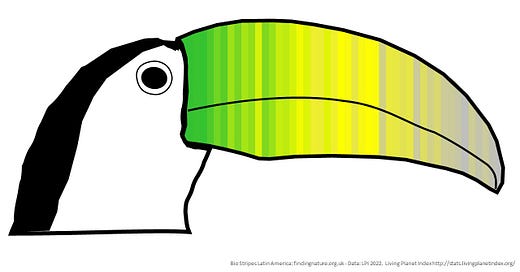

There’s also a charming version on the beak of a toucan, representing the biodiversity stripes for Latin and Central America.

(Latin Bio Stripes – Data: Living Planet Index. Source: Miles Richardson.)

The rationale here is all about creating awareness through better visualisation, in the hope of creating a better connection with nature. As he notes:

There is global recognition from organisations such as the UN and IPBES that the failing human relationship with nature is an underlying cause of the environmental crises. Greening the grey can rebuild the human-nature relationship, both through providing opportunities for people to take part in caring for nature, but also to enjoy a greener and more colourful world.

As he notes of the UK data, for example, the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries on the planet. Less nature means less connection to nature. So no surprise to find Britain at the bottom of a European league for nature connectedness. And in turn that means that British people don’t get benefits from biodiversity and nature connectedness in terms of improving health and wellbeing.

It’s early days, and Richardson is still looking for good data sets—he asks readers if they know of data sets that can render the UK biodiversity decline better, or images that will work as a backdrop.

But this seems to me that it has some potential as an awareness tool: here’s his image showing the data for 944 freshwater fish species, again from the Living Planet Index, with a simple indicative graphic laid over it.

(Freshwater Bio Stripes – Data: Living Planet Index. Source: Miles Richardson.)

2: Inflation and the unravelling of low-interest economics

I had some comments in response to my piece yesterday on inflation, some sceptical. I discussed an article by Jayati Ghosh that argued that the cause of inflation wasn’t excess demand—as goes the received wisdom of the central bankers right now—but was a combination of market power and speculation. On LinkedIn Jeffrey Roberts suggested a third factor that was causing inflation:

Instability in a globalized system. While the 1970s had its fair share of global instability, it took place in a different geo-political configuration including a great power Cold War and a much less globally integrated economic system. Europe is beholden to Russian energy exports and the wider world to Ukrainian grain shipments in ways that would have been unimaginable in the 1970s. Throw in to that China’s role as global manufacturing hub – still unwinding from COVID impact – and we have an historically unique set of relations giving way to a distinctive inflationary environment.

Walker Smith, in contrast, from a US perspective, suggested that we are watching the post-pandemic effects—in particular relief payments—unravel themselves:

(T)he IMF is predicting that inflation in the US will be in the neighborhood of 2% by the end of next year because of a decline in demand due to people running out of this extra money. At the same time, we're seeing shipping untangle and inventories climbing, both of which will ease pressure on prices. Net, net, I think we're going to see normal market forces at work, not greedy monopolists distorting normal market forces. I could be wrong... But my point is that we are not in the middle of a real-time, real-world experiment that will answer the question about whether greedy monopolists are the cause of inflation or normal market forces of demand outstripping supply.

All this reminded me that I’d been meaning to mention an interview with the historian and investor Edward Chancellor, whose recent book The Price of Time argues that speculative bubbles follow periods where bankers have suppressed interest rates, for whatever reason.

After years of ultra-low interest rates, central banks created a bubble in pretty much every asset class, they facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they allowed an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness.

The interview is in the Swiss magazine The Market.

I’m not going to do the extended interview justice here, but it certainly comes under the general heading of ‘interesting if true’. He traces the history of the idea of interest payments back 5,000 years—which suggests that the book should probably be read in tandem with David Graeber’s equally long-range history of debt.

One of his findings on a longer view is that speculative bubbles follow periods of low interest rates:

There’s always the idea that speculative bubbles are formed around the invention of a new technology... What I argue is that when interest rates are pushed down too low, people are driven into speculative endeavours and chase returns. One way of explaining this is that in investment, we need a discount rate in order to discount future cash streams back to a current value. It’s the first thing we learn in finance. So it’s not surprising that you should have the most speculative ventures rising to very high valuations when the discount rate is very low.

The recent period of ultra-low interest rates was driven by a fear of deflation by central banks, which was founded in the experience of the 1930s depression, when deflation and recession combined to disastrous effect. But that may have been a unique instance of this, according to research published by the Bank of International Settlements.

He describes the effect of this low interest policy as “the Everything Bubble”:

The interest rate environment of the past years has created an enormous bubble in pretty much every asset class. That’s what I see as the ultimate cause of the «Everything Bubble». During the Covid market mania of 2020 and 2021, the Everything Bubble was evidenced in the overall valuation of the US stock market, extremes of tech companies, unlisted unicorns, in meme stocks like Gamestop, speculative frenzies around cryptocurrencies, baseball cards, vintage cars, art.

But: the problem with keeping interest rates low is that, in his view, it’s impossible to normalise them without collapsing the economy:

Financial markets have experienced great turbulence this year, even though interest rates have only started to pick up and are still very negative in real terms.

So this was only the beginning?

I don’t know. What I can say is that when you normalize interest rates, you see that a lot of valuations don’t make any sense, whether in real estate or equity markets.

That reminds me of Warren Buffett’s famous line, that ‘only when the tide goes out do you find out who has been swimming naked.’

In an environment of rising interest rates, a lot of businesses that only thrived because of cheap capital will run into trouble. This applies to zombie companies as well as to super high-tech stuff like space tourism companies. Take your classic zombie, say an Italian cement company, and a flying taxi venture that had a flashy SPAC takeover transaction: The common thing is they both rely on cheap capital and low interest rates in order to survive.

Anyway, this takes us back to inflation again. The effect of all of this has been to create “much lower interest rates, much higher debt and much more inflated asset valuations” than we had in the 1970s. This is as a result of a ‘debt supercycle’ that has lasted several decades and has been stoked by central banks to solve a series of economic problems. That debt supercycle is now coming to an end.

But the similarity Chancellor sees with the ‘70s is that as a result of the debt and asset valuations, we have a set of distributional problems, and inflation is a mechanism for resolving these, although it doesn’t resolve them in a tidy way:

Going forward, we’ll have more inflation in the stop-go fashion that I described, we’ll have rising interest rates and a lot more volatility in financial markets. That will make life much more difficult for investors. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, because many investors made too much money by not really doing anything... Of course, inflation is not a smooth process, it’s very painful for some people who are badly positioned.

In passing: Chancellor is not kind to central bankers (“They have a rather narrow field of vision, a tendency to congratulate themselves, and a very profound tendency to reject dissonant information”). And I also learned that the first recorded instance of financial arbitrage goes back to Mesopotamia, 5,000 years ago.

j2t#359

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.