Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. For more recent readers: I’m away at the moment, so am posting when schedule and internet connection permit. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: How streets should work

The urbanist Dan Hill is one of the most interesting writers about cities out there at the moment, perhaps because he’s a practitioner whose writings are informed by his practice (he’s currently based in Sweden). He tends to write at length, on Medium, in flurries, but we’re in the middle of a flurry at the moment.

So this post is pointing you to a long recent essay using some notes by Brian Eno on cities as a starting point. I’m not going to try to summarise an article that Medium says has a reading time of 32 minutes, but instead just to pick out two or three ideas.

(Source: Brian Eno/Dan Hill)

If there are core ideas in Dan Hill’s work, they are about the importance of the human scale in the urban space, and also the importance of affordances: the little design cues and clues that we use to navigate it.

Culture is the whole point of cities

The whole point of cities is culture, not efficiency... And if we recognise that streets are the basic unit of cities, then they must be about culture too; they convey what we stand for... This means decision-making around streets can be realigned around more meaningful questions: such as ‘What is a good street?And who for?’, rather than the crudely damaging, ‘How might this thoroughfare best accommodate 1000 vehicles per day?’ In other words, strategic design involves changing the mental models that are used to frame the question of the street, redesigning the conditions that produce the street.

Think like a gardener, not an architect

This is the first of Eno’s principles, and connects with a lot of other emerging thinking about how to create more organic spaces and more organic practice. Here’s Dan’s take on it:

the practices of gardening provide our most fruitful metaphorical terrain: the slower dynamic of organic growth; the sensibility of care, attention and cultivation; its regenerative potential; embodying systems and ecosystems, as well as cultural expression and social justice; the understanding that a garden can be planned, yet not controlled, and a thousand other things. I’m currently reading Leon Van Schaik’s new book Doing, Seeing; Seeing, Doing... As with a garden, the principle of setting off in a clear direction or set of ideas, spatial, material and otherwise, yet not being overly concerned with the idea of An Ending, seems entirely right. A street cannot be finished, any more than a garden can be.

Artists are to cities what worms are to soil

Another delightful reference to soil and earth, and their associated dynamics, but this principle also clearly foregrounds the preeminent role of culture in the city, rather than the overly technical worldview that usually manages streets. (Of course, the word ‘culture’ emerges from ‘cultivate’.)... So this principle suggests a few things: questions of value (how would streets be designed if ‘delight’ was the ‘key performance indicator’ and how might that be done?).

Low rent = high life

A follow-on question of social justice, and similarly direct, here addressing the affordability of the street, and thus the accessibility to meaningful life on the street. But in its delightful counterpointing of high and low—reversing many of the assumptions about rent and quality of life in four words—this is both a question of justice and generating capacity for invention and adaptation, by producing diversity. By keeping space affordable, and not only in housing but in shops, studios, workshops, community centres, storage, and so on, the street can build a capability and capacity for ongoing change at its core. This runs counter to the unethical pursuit of rising property prices from many, perhaps most, economic development functions in city governments. Deliberately keeping rent low ensures a vitality to the street, and thus to the neighbourhood.

(Picnic in the background, picnic table (with tablecloth) in the foreground. Image: Dan Hill)

Shared public space is the crucible of community

The street is our most potent, complex shared public space—and that one of the goals of such environments must be to generate community, as if a crucible. This, again, is a fundamental switch in outcomes and drivers of decision-making. The next phase of Vinnova’s street missions includes new forms of ‘value model’, suggesting we should be a little more specific about the broader range of value that a good street can produce. We are constructing models and practices for better understanding—and prioritising—biodiversity, sustainability, public health, social fabric, and economic outcomes... These outcomes must be linked to both material and spatial alterations—what forms of architecture and design can create such a crucible?—as well as new kinds of ownership, operational and governance changes.

But this is the formal way to express all of this. There’s an informal way as well.

But rather than all these words, here, in this previously inert space on a sunny Sunday afternoon, a picnic! And the lovely touch of the tablecloth under the plates and cups, laid out over the wooden Street Moves kit, is somehow unbelievably touching, a domestic touch that implicitly describes shared ownership by the community.

It’s rich stuff, and it’s also stuffed full of links and references. I’ve only scratched the surface here. If you’re at all interested in streets, there’s a wealth of ideas in here.

#2: The world economy is stuck

We’re used to hearing that capitalism is an engine of growth. But right now, it’s not working very well, and hasn’t been working very well for some time—since long before either the global financial crisis or the global pandemic.

A recent article by C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh at the Real World Economics Review blog makes this point in a number of charts. (Some of the language is slightly technical).

And of course they’re clear that GDP is a terrible measure of most things that make societies work—their point is that even on its own terms capitalism is malfunctioning.

Exhibit 1 is the long-run decline in global growth—going back to the 1960s.

Source for all figures: World Bank World Development Indicators online, accessed on 4 Sep 2021.

(The next time someone tells you that everything is speeding up exponentially, it’s worth asking them about the orange line on this chart).

It’s also worth noting that this declining rate of growth leads to all sorts of other problems, as investors and financial actors try to maintain their investment returns in an environment where economic returns are falling.

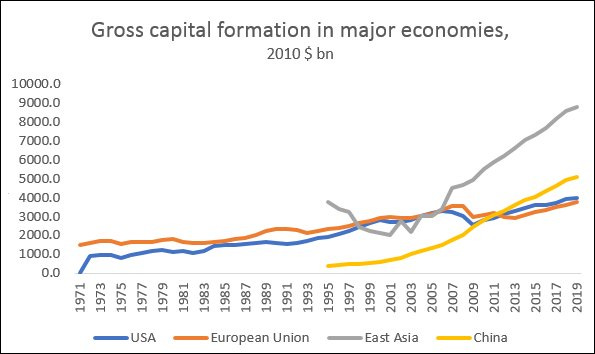

Exhibit 2 is about the flatlining investment. To the extent that this has increased globally, it has been pretty much entirely because of new investment in China and East Asia. Investment in both the USA and Europe has been pretty flat. Again, if our economies were accelerating in the way that tech evangelists and others say they are, this figure would be climbing everywhere.

But there’s actually a cycle here where expectations of poor returns lead to low investment.

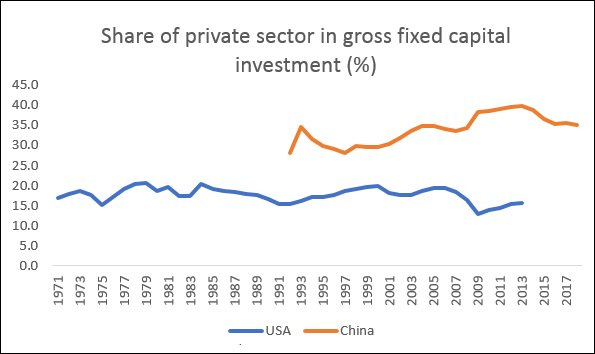

The other thing that’s notable is how little investment is coming from the private sector.

Exhibit 3 here shows that in China, only around 40% of investment is coming from the private sector, while in the US it is significantly lower—20% is less. Governments are doing most of the work..

The authors say:

This is really quite an extraordinary pattern, which completely confounds the general perception of private accumulation being the driving force of economic expansion during the phase of globalisation. At least in the two largest economies in the world, it was actually public investment that was far more weighty and substantial in fixed capital formation, accounting for more than four-fifths of total fixed capital formation in the USA and more than two-thirds in China.

In fact, this is all part of a bigger story. Since the global financial crisis, as Adam Tooze has pointed out (but I can’t find a link), most of the world’s large economies have been completely dependent on central banks pumping money into them in vast quantities to keep them afloat. The pandemic has exacerbated this.

This investment data tells us the same story:

This underlines the fact that global capitalism is on life support provided by governments. Not only is central bank intervention through massive creation of liquidity now essential even to maintain economic functioning in the advanced economies, but even the investment that does occur is mainly because of public sector activity, with private investment playing at best a supporting role. Purely on its own terms, global capitalism is failing.

j2t#163

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.