10 January 2022. Masks | Bowie

Masks, pandemics, and making decisions under uncertainty| Stars and starmen

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Masks, pandemics, and making decisions under uncertainty

I’m not quite sure of the point of writing 80-part threads on Twitter—if you have that much to say, write it as an article and tweet the link instead. But nonetheless, a long thread on masks from July last year by Professor Trisha Greenhalgh popped up in my feed, and seems worth discussing. Not so much because of masking, although that seems to be intermittently a controversial issue at the moment, but because of what it says about making public policy under conditions of uncertainty.

Greenhalgh is Professor of Primary Care Policy at Oxford, so this is her home turf.

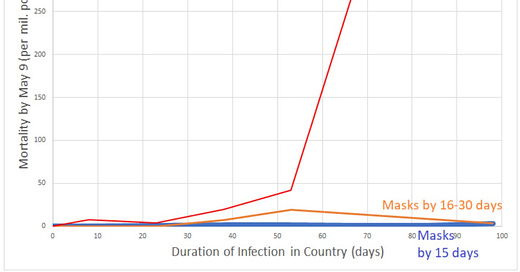

The first chart is an eye opener: the difference in pandemic outcomes between countries with Covid that introduced mandatory masking within 30 days of their first case.

(Source: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/103/6/article-p2400.xml)

The ‘mask’ countries are mostly Asian, probably because they learned from their prior experience with SARS and MERS. The ‘non-mask’ countries are mostly Western. There are cultural, political, and trust differences at play here as well, of course.

But masks clearly have a big effect—check the detail in the bar chart, but the green line is wearing a mask, the red line is social distancing, and the blue line is social distancing and mask wearing:

So why didn’t everyone do this? Because the waters got muddied by science. Quite early on in the pandemic, Greenhalgh and others—looking at the Asian data—wrote an article in the BMJ suggesting that wearing masks would be a sensible precaution. We didn’t know at the time if the Asia data was correlation or causation, and the evidence was weak. So critics suggested that because of this “empirical uncertainty” it was better to do nothing. Greenhalgh is impatient with this view:

Tragically, WHO along with Public Health England, CDC and many other bodies around the world all focused on two things: a) the lack of incontrovertible, definitive evidence and b) speculation about possible harms. For many mission-critical weeks in early 2020, these bodies persisted in saying “there’s not enough evidence of benefit” and (without evidence) “there could be harms”, and insisting that these arguments justified inaction.

Her view is that facemasks were being judged by the same scientific and medical standards as, say, vaccines and medicines, but the two aren’t really comparable:

A bit of cloth over the face simply doesn’t have the same risks as a novel drug or vaccine, and doing nothing could conceivably cause huge harm. Arguing for “caution” without engaging with the precautionary principle was scientifically naïve and and morally reckless.

As she says later in the piece, “Your cotton mask is no more likely to kill you than your cotton T-shirt which you pull over your head.”

There’s lots more in this extended thread, and if you’re interested in the detail it’s certainly worth reading.

But I was interested in it because it also seems to play into the societal debate that we’re having about how we understand science.

The first is that our current medical research models are dominated by RCTs—randomised controlled trials—even when that’s not the best or most appropriate way to assess the effect of something. (Greenhalgh spends quite a lot of time on this in her piece). But even suggesting that an RCT might not be the right way to go is to call scorn on you.

Second, one of the reminders of the pandemic is how difficult it is to get scientific organisations to change their minds, even in the face of evidence. There’s been quite a lot of discussion, for example, of how organisations such as the WHO got locked into the ‘droplet’ theory of how the coronavirus spread (hence all of that surface cleaning) even as it became clear that the mechanism was an aerosol (where masks, being in the open air and ventilation all have more impact). Greenhalgh also discussed this in her piece. In short: killing off a long-held view that is held by senior members of an organisation, and has been espoused by them, is hard.

And third, although we’ve heard lots of noise in the pandemic about ‘following the science’, our literacy about how ‘science’ is formed—especially in the face of conflicting data and changing environments—is actually quite poor. The ‘science’ is a mess of competing suggestions and hypotheses until one eventually emerges as a better explanatory fit to what’s actually happening out there.

Indeed, in another article, Greenhalgh suggests that the pandemic might be a big challenge to many of the assumptions that sit behind ‘evidence based medicine’:

evidence-based medicine rests on certain philosophical assumptions: a singular truth, ascertainable through empirical enquiry; a linear logic of causality in which interventions have particular effect sizes; rigour defined primarily in methodological terms (especially, a hierarchy of preferred study designs and tools for detecting bias); and a deconstructive approach to problem-solving.

There’s a final point here as well. As Stephen Bush wrote in a newsletter before Christmas about the UK government’s pandemic policy,

(T)he dirty little secret of the British government’s coronavirus policy is that it has never really been about saving individual lives: it has always been about keeping society and the economy as open as you can without the NHS keeling over. Most of the time, that has been the policy by accident rather than design, but, nonetheless, that has actually been our coronavirus policy.

And it seems very likely that—had we got into the habit of wearing masks sooner—the government could have achieved this objective without repeatedly taking the NHS close to collapse. But going down that line of enquiry takes you into the murky waters of right-wing libertarian ‘thinking’, critiqued so well recently by Simoin Wren-Lewis. And life’s too short for that.

#2: Stars and starmen

I’m a sucker for pieces that deconstruct the way that songs work, which is what Kirk Hamilton has been doing for three years now at his Strong Songs podcast. This time last year he marked the anniversary of the birth and death of David Bowie with an episode that explored two connected songs, ‘Space Oddity’ (from 1969) and ‘Starman’ (from 1972).

'Space Oddity’ came out in the same summer as the moon landing, and was, after a false start, his first hit single, eventually reaching #5 in the charts. In fact it was his only hit before 1972, when Bowie’s construction of his ‘Ziggy Stardust’ persona made him a star.

One of the reasons why ‘Space Oddity’ took a while to become a hit was because it essentially a dark song. And it’s a dark song even before—spoilers—the mission goes wrong. As Hamilton says:

'Planet Earth is blue, and there’s nothing I can do’. After all the pomp and circumstance of the launch and Ground Control congratulating Major Tom on this great accomplishment, he’s kind of left alone up in space looking down on the earth, and it’s a very melancholy thing. It would be a very sobering and lonely experience... It’s actually a song about a guy who is launched into space and is left there and just floats away.

The line ‘Planet Earth is blue’ also feels like a nod towards the first edition of the Whole Earth Catalog, which came out in 1968, with its cover showing earth from space. Two years earlier Stewart Brand had sold badges on the street in Berkeley asking, ‘Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?’

(The first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog, Fall 1968. Via openspace.sfmoma.org)

I’m not great when it comes to musical analysis, but without being able to follow all of it, you still get the strong sense of how rich and complex the song is:

Taken as a whole, it’s a more experimental and strange song than I gave it credit for before I learnt it for this episode... The particulars are actually more unusual than your average rock and roll song. It tells such a clear story, it kind of has a script with different characters, it feels more like a theatrical production than a rock song.

'Starman’ is—he suggests—a reworking of ‘Space Oddity’, but one that removes almost all of the musical and production oddities of ‘Space Oddity’.

'Starman’ also turns the story of ‘Space Oddity’ on its head:

If in 1969 ‘Space Oddity’ told the story of a man launching into space and then getting lost and drifting away, 1972’s ‘Starman’ tells the story of an extra-terrestrial being... arriving in orbit and waiting to come down to earth to greet us all. It’s a theatrical and cinematic story, in the same way as ‘Space Oddity’, even if it is exciting and hopeful rather than melancholy and sad.

But even though it is a more straightforward song than ‘Space Oddity’, Hamilton points out that Bowie is still using chord progressions drawn from Broadway and musical theatre as much as conventional rock chords. The melody of the chorus, for example, consciously draws on Arlen’s melody on ‘Over The Rainbow’. There’s also some clever production and electronics on that morse code effect that brings in ‘Starman’s chorus.

There’s a sense of musical story telling here too. The Starman’s chorus may be built on Broadway chords and a sweeping string arrangement (written by Mick Ronson), but when ‘all the children boogie’, the guitar chords could have come straight out of the T. Rex glam rock songbook.

Maybe Hamilton ran out of time, but there’s obviously a third song in this triptych, which he doesn’t explore here. (And I don’t want to seem like I’m carping, since I learnt a lot about two songs I thought I was very familiar with).

By the time Bowie gets to ‘Ashes to Ashes’, on Scary Monsters and Supercreeps, Major Tom—perhaps also biographically—has completely failed to deal with celebrity.

Ashes to ashes, funk to funkyWe know Major Tom's a junkieStrung out in heaven's highHitting an all-time low.

Hamilton has a conceit that links ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Starman’—yes, Major Tom got lost in space, but he didn’t die. Instead, he hitched a ride on a starship and sailed the galaxy. Three years later, he comes back to earth as a benevolent starman.

And frankly, for any other performer and any other pair of songs, this would seem fanciful. But as I’ve written elsewhere, Bowie’s life and work was “about fame, the getting of it, the holding of it, the letting go... the otherness of stardom.” And perhaps the best way to understand Bowie’s whole huge outstanding body of work is as a conversation with himself about what it is to be a star. Pun intended.

Notes from readers: Thanks to my transport futures colleague Anna Rothnie, who responded to my collection of memes about roadspace last week with a picture of a Polish mural (via Marco to Brommelstroet on LinkedIn). The caption translates as ‘Your car, my breath’.

j2t#239