10 February 2022. Protest | Streaming

The Insulate Britain campaign picked the wrong targets. Streaming services should take cinema releases seriously.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The Insulate Britain campaign picked the wrong targets

The news that the Extinction Rebellion campaign ‘Insulate Britain’ has folded itself has prompted a reflective post on the nature of protest by Jeremy Williams at his excellent Earthbound blog. The group issued a statement earlier this week headed “We must acknowledge we have failed.”

As Williams reminds us, the demand that we should Britain should insulate its homes was certainly backed by the evidence:

According to the Building Research Establishment “the UK’s housing stock is the oldest in Europe – probably the world”. It desperately needs to be brought up to scratch. The benefits are also obvious, and manifold. Efficiency measures save households money. Insulation makes homes healthier and more comfortable. It also cuts carbon, and this is essential to Britain’s climate targets.

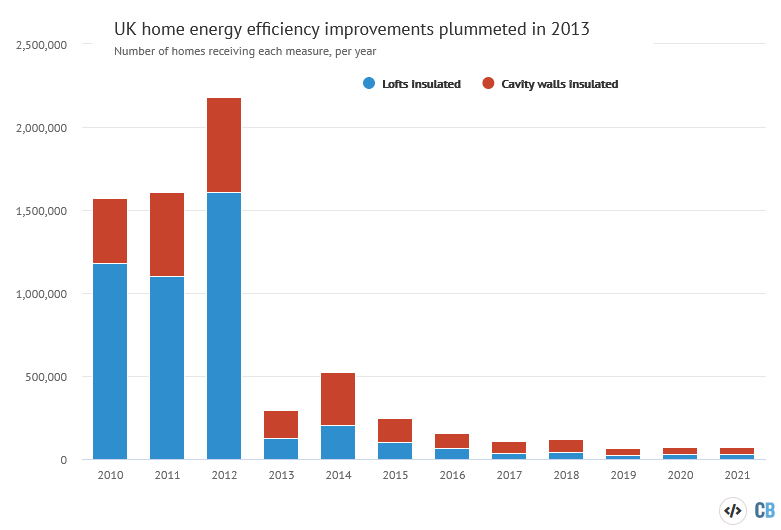

And insulation programmes have plummeted since 2013. We’re doing less and less about something that in theory has become more and more important.

(Number of UK homes having their cavity walls (red bars) or lofts (blue) insulated in each year. Source: Climate Change Committee 2021 . Chart by Tom Prater for Carbon Brief using Highcharts. Via Earthbound Report.)

So, as Williams observes:

Insulate Britain had clear demands that anyone could understand, in response to an obvious failure of government. What they wanted wasn’t controversial, and millions of people would benefit from it. So what went wrong?

Like XR, which ‘Insulate Britain’ spun itself out of, it was a direct action campaign. It sought to pursue its aims through tactics of civil disobedience, including a programme of direct action that involved, for example, blocking roads.

Williams, who is an environmental activist, notes that while he supports fully the demands that ‘Insulate Britain’ made, he wasn’t a supporter of their campaign. This is because of the gap between the tactics and the objective:

countless thousands of ordinary people were inconvenienced by their actions. And my problem is that there is no connection between motoring and insulation. This matters. The current wave of climate protest is inspired by pioneers of non-violence such as the US civil rights movement.

But there’s an important difference. In their refusal to leave, or their requests to be served, civil rights protesters were making a demand that spoke directly to their status as citizens who were discriminated against.

Some Extinction Rebellion actions are more closely directed at the things they want to change—blocking traffic, for example, which accounts for 28% of UK carbon emissions. For Insulate Britain, there was no connection between what they were demanding and what they were doing.

And—even if you believe that direct action is the most effective way to raise the profile of insulation as a policy demand, there are ways to do this that makes this connection more explicit, as Williams points out:

We know that Taylor Wimpey, for example, successfully lobbied against plans for zero carbon homes. Imagine that their building sites came grinding to a halt, costing them thousands in lost work days. They would call for arrests, but behind the scences they might also think again about insulation. The general public would understand the connection – if they heard about it. But even if they didn’t, the signal would get through to the decision makers.

Williams points out that it might be too early to declare failure. The suffragettes campaigned for a decade before they succeeded, whereas Insulate Britain had been going for a year. And it seems that they might regroup in a way that leads to regaining public support, which declined over the life of the campaign.

One note from me. Housing insulation may be one of those climate demands that doesn’t need direct action to make its case. As pointed out above, it has a lot of winners, especially as fuel bills go through the roof. Insulation—as we’ve known ever since the Green New Deal did the sums way back when—spreads employment around the UK, puts people into work in localities all over the UK, and even supports the so-called ‘levelling up’ agenda, or would if it was a programme instead of a slogan.

And it’s not exactly controversial. The House of Commons Business Energy and Industry Strategy Committee recommended it to the government in 2019.

Yes, insulation is expensive, and typically has a long financial pay-back period (although a long payback period is better than the planet over-heating). On the other hand, it has a short carbon payback period. It’s also necessary—necessary as in essential—if the UK is going to get to net zero by 2050.

There ought to be a way of constructing some kind of carbon impact bond that bridges the gap between those two timeframes. And there’s every reason to campaign to direct some of the energy sector’s excess profits into insulation programmes.

2: Streaming services should take cinema releases seriously

At Slashfilm, there’s a speculative piece on whether streaming services might decide to buy cinemas. That doesn’t make much sense—you can have your films shown in cinemas without having to own them, and in some countries I think it’s still illegal for studios to own cinemas (although no longer in the US).

But the logic behind the argument tells us something about the limits and the economics of the streaming market. Well, the economics of the streaming market if you’re not able to cross-subsidise your streaming service because it brings other business benefits, as it does for both Apple TV+ and Amazon Prime Video. So we’re really talking about Netflix.

The logic that sits behind this idea is that films are very expensive to make. Red Notice, for example, apparently Netflix’ most successful film of all time, cost $200 million to make—which is a lot of monthly subscription payments. Maybe you can take that when the platform is still growing—it acts as a form of subscriber marketing—but when subscriber numbers plateau, as they have for Netflix, it’s harder to justify.

At the moment, quite a lot of the movies that are released by the streaming services do get a cinema release, but this is usually a token affair, a week or two, designed to make sure that they can qualify for awards. (Red Notice was in the cinema, at “selected theaters,” for a week before it went live on Netflix.)

It’s also an inducement for directors—if you’re competing to win a hot project, then promising a theatrical release, even a short one, is going to be attractive to them. (The Irishman, for example, funded by Apple, had a cinema release).

But let’s go back to the economics: as the Slashfilm piece notes, a studio that spent $200 million dollars on a movie would be looking for a decent return:

A studio would typically want to see hundreds of millions at the box office in return for that kind of investment, if not close to $1 billion. For most streaming services, it's purely about what value it brings in terms of subscriber dollars. It takes an awful lot of monthly subscription fees to make up that kind of money, especially when considering the sheer volume of high-dollar movies and TV shows a service must produce to keep subscribers happy. Netflix spent around $17 billion on content last year and that number is expected to go up in 2022. Peacock, meanwhile, lost $1.7 billion last year while trying to keep up with the competition. The realities of this business are brutal.

The article doesn’t really work this idea through—it gets a bit hung up on whether buying cinema chains is a good idea. (It isn’t—distributors like cinema chains need to be able to deal with everyone who has content to make their business model work, and the minute a streaming service owns a chain, this stops working. You start getting conflicts of interest.)

But as it does say, from the point of view of the streaming service, exclusivity of content when it goes into the home is critical.

So I’m just going to construct the rest of the argument for them.

- Netflix, say, starts taking cinema release seriously, meaning that it gives its films the theatrical run that their box office takings deserve.

- If they do well, they win, and collect the revenues. When they flop, they’re barely worse off than they are at the moment.

- When the ‘cinema window’ closes, say after three to six months, depending how it does, they still have exclusive streaming rights to it, and it gets shown on Netflix.

The Slashfilm article wonders why the cinema chains would “help” Netflix. They’re not “helping” Netflix; they’re simply accessing more content on similar terms as they’d access content from other studios.

And what about the Netflix customer? Yes, the film arrives on Netflix later than it would have done, but this is only going to be true for a minority of shows, and—since its exclusive to Netflix—its not available anywhere else, except the cinema, before then.

And one of the curious things here is that there’s some evidence that says that when it comes to media people enjoy seeing something again. So even those Netflix customers who paid for their cinema tickets are probably going to be happy to have the chance to access that film, for free, when it launches on Netflix.

j2t#260

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.