11 February 2022. Insulation, again | Internet

The whole approach to retrofitting is just plain wrong. Improving manners on the internet.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The whole approach to retrofitting is just plain wrong

Robyn Pender is a buildings scientist who reads Just Two Things. She wrote to me after I published my piece yesterday on Insulate Britain to say that the worst thing about the Insulate Britain campaign was that they had fallen for the insulation industry’s propaganda. And to be honest, given my discussion of the issue, it sounds as if I had as well.

She attached an article she’d had published last year in The Journal of Architectural Conservation—behind an academic publisher’s paywall unless you have academic access—which I’m going to pull out some extracts from. In short, though: this whole problems needs re-framing. We need to be thinking about ‘thermal comfort’ instead of insulation.

We have now had rather more than two decades of retrofit programmes aiming to reduce energy and carbon in the built environment worldwide, and the kindest thing that can be said is that the results have been disappointing. At best many retrofits have failed to achieve meaningful reductions, and at worst they have led to serious problems for the building and its occupants.

This is down to the way we changed building design when fossil fuels suddenly became available to us—broadly from what she calls a ‘traditional’ solid wall design to a ‘modern’ hollow wall.

Currently, buildings are mostly constructed with carbon-intensive (and often short-lifespan) materials that are expensive to produce and transport, using systems that make maintenance difficult, if not impossible. Many of the resulting buildings are not usable without mechanical services... Designs are usually highly specific to particular tasks, and can therefore be very difficult to adapt to changes of use.

The outcome of this is a very short building lifespan. I’ll come back to what ‘thermal comfort’ is, but in her article, Pender argues that we’re approaching this whole problem in a way that means that we won’t be able to solve it.

Current approaches to retrofitting represent a classic case where the means chosen to meet an end conflict with the desired outcome; as described by Brian Christian in his book The Alignment Problem: Machine Learning and Human Values. (A)lignment problems are common in modelling of the built environment. This is especially true of the models that are being employed to predict energy use or the impact of retrofits. The factors involved in energy consumption are poorly understood, leading to poor predictions, especially in buildings of traditional construction... Therefore the actions suggested by retrofit modelling rarely deliver the promised energy savings.

There is a whole set of issues with the current approach to retrofit. These include:

- Difficulties in assessing carbon and energy

- Poor understanding of how building systems and materials behave in situ

- Poor integration of modern mechanical systems into buildings

- Poor understanding of retrofit materials

- Reliance on market-led retrofit solutions.

These are effectively all issues to do with an approach that’s designed to adapt a building designed for a fossil fuel powered world to work in a low carbon world.

But the deeper problem is about the twin issues of ‘thermal comfort’ and also understanding what people did when they were building for a pre-industrial revolution low carbon environment. The current ‘insulation’ model starts from the wrong place:

(It presumes) that for a building to be comfortable and usable, it requires some form of space heating or cooling. If this were indeed the case, saving energy and carbon would require action to prevent conditioned air being lost. Essentially, the building envelope would need to be sealed. In reality, thermal comfort is dominated by other factors, including occupant control. The critical importance of radiant body heat loss was well understood in the past, and dealt with using radiant breaks (simple passive interventions such as cloths hung on the wall and made into partitions and canopies, or wooden panelling, which stop body heat being absorbed by the building fabric).

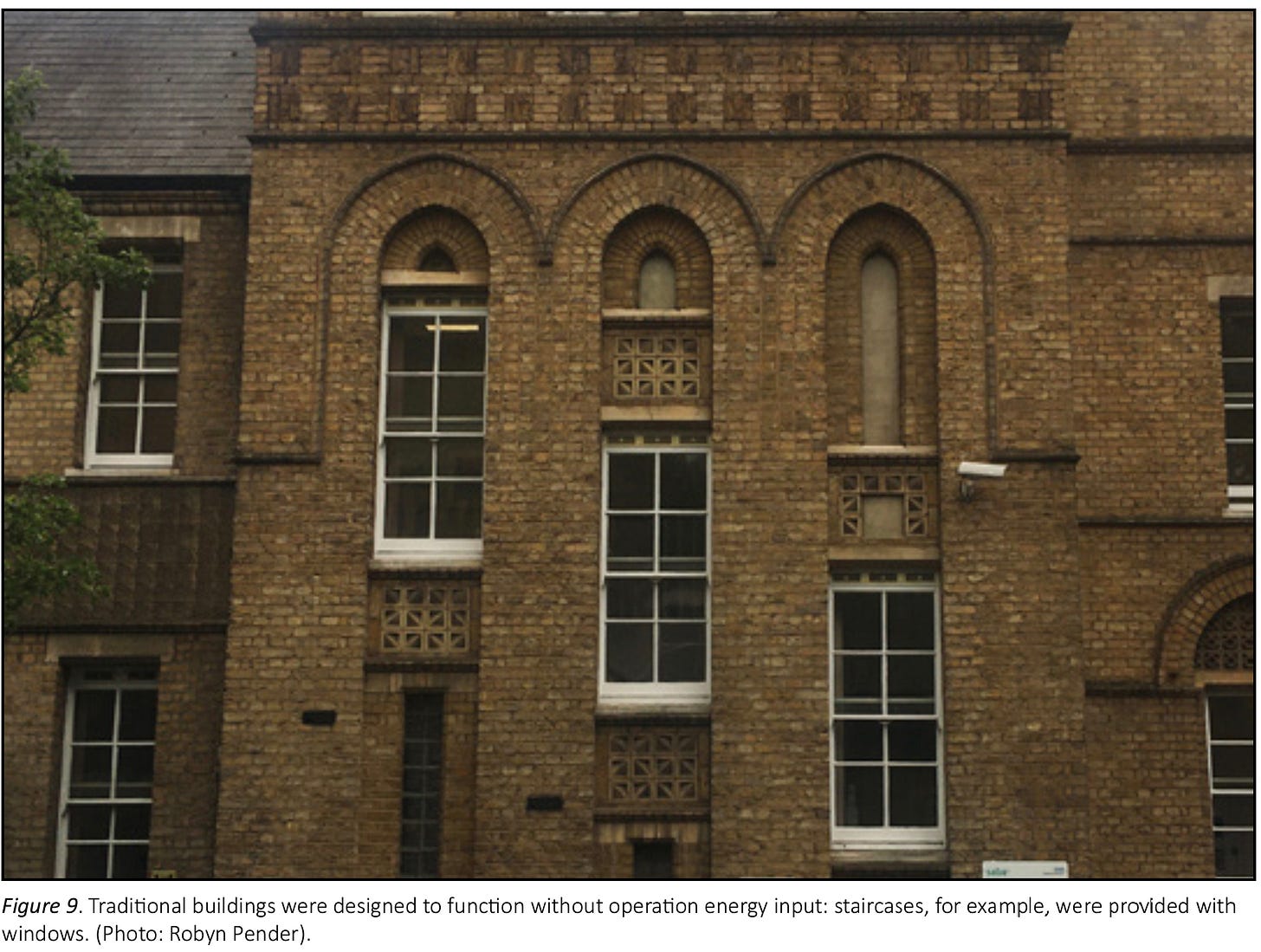

At the same time as we’ve lost this knowledge about thermal comfort, we have also lost an understanding of many of the features that used to be incorporated into older buildings to keep them warm, which is one of the reasons we think of old buildings as cold and damp:

(M)any vernacular buildings are poorly understood, poorly maintained, and poorly operated. With the purpose of weathering details such as lime renders, hood mouldings and cills no longer understood, when these eroded, they were removed rather than being repaired or replaced. Most older buildings are now missing at least some of the features that once kept them in good condition, and ensured dry and comfortable interiors... When the lost features are reinstated, occupants are commonly struck by how much warmer, as well as drier, the building now feels to them.

Because materials were both difficult and expensive to transport, older buildings were constructed with an emphasis on care and repairability. In contrast, in the fossil age, there is “an emphasis on construction rather than care: indeed, the resulting buildings are often very hard to maintain, which is one of the factors encouraging short lifespans.” In turn, this increases their emissions impact, since demolition is energy intensive and few materials are reused.

So what does the post-carbon world of 2050 look like? In some ways, it looks back as much as it looks forwards:

(B)uildings (are) intrinsically part of their local environment, and operated by knowledgeable occupants. It would however incorporate piped water and some form of electricity supply, albeit much more effectively than at present, and it would put no emphasis on cars, electric or otherwise. It would not have air conditioning, and perhaps not space heating either, but the buil’dings would be more healthy and comfortable than at present – noting that ideas of comfort evolve, and in the fallout from the pandemic are likely to once again include significant ventilation, as was always sought after in the past.

In futures terms, then, this is an example of something from the past that has been submerged in the present re-emerging to shape the future. I think I’d like to understand more about what the ‘thermal comfort’ approach looks like at scale. as a strategy for the 26 million or so UK homes that need to be brought up to standard for a net-zero world. But that can be a conversation for another time.

2: Improving manners on the internet

I recorded a panel discussion today for TRT World on the prospects for the metaverse. The other panellists were Sylvia Pan of Goldsmiths and Tom Ffiske of the Immersive Wire. It should go out next week and I’ll link it here when it does.

Part of the conversation turned—inevitably—to managing bad behaviour in this space when it finally arrives.

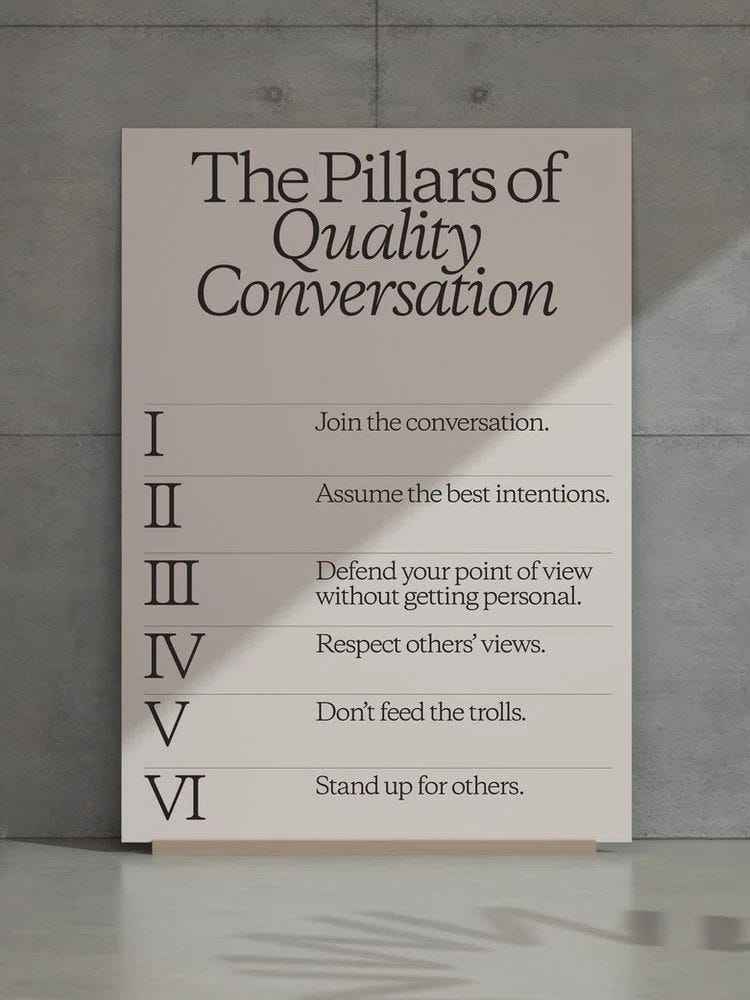

So I was struck to see a typographical attempt to improve the quality of online behaviour, in a rebranding of OpenWeb by the design company Collins. (The story is on It’s Nice That).

The branding strategy was, in effect, to recreate the typography of the coffee shop era in order to shape better behaviour.

(Collins, via It’s Nice That)

“The internet is filled with environments that tolerate, or often, incentivise and amplify awful behaviour,” Collins design director Megan Bowker explains. “OpenWeb identified this issue as one they could take on with their product. Eliminating trolls is the baseline... For Collins, this also meant asking: “What role could design play in empowering publishers to be good and better hosts for important conversations?”

The design solution was produce clean versions of the kinds of typography that were more common in the 19th century, almost a visual clue that old-fashioned manners were also expected:

19th and 20th-century print – from newspapers to literature – was used as inspiration. In doing so, Collins hoped to imply “considered attention” by hinting at “a time when it took manual labour to put words into existence (carefully setting type with metal and ink)”, Megan tells It’s Nice That.

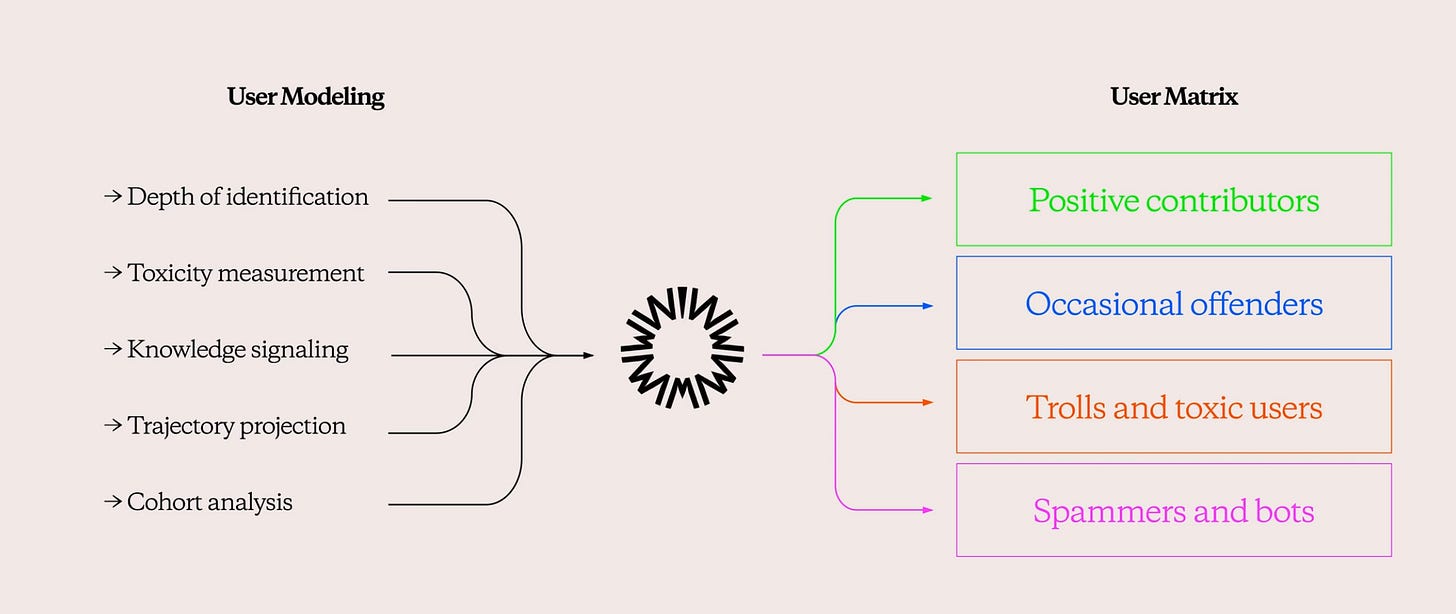

It’s not all backward looking, however. There are some smart-looking interactive graphics that underline the way that OpenWeb approaches the internet. These are animated on the site, but I have captured one as a screenshot here:

(Collins, via It’s Nice That)

If you are interested, it’s worth visiting Collins’ web page about the project, which has some interesting interactive pages.

And one last note for the weekend.

It is 58 years this week since The Beatles first appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in the US. It was the first of three appearances on the show in the space of three weeks. That first appearance was watched by 73 million people and probably confirmed their arrival as the biggest band in the world. Here’s a moment of that youthful energy—singing, as it happens, one of my favourite of their songs. You know what I mean.

j2t#258

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.