1 March 2024. Navalny | Geoengineering

Navalny: ‘A Russian counterpart to Mandela’? // Geoengineering climate change. [#547]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for the slightly light publication rhythm at the moment: I’m doing a lot of projects right now. Have a good weekend.

1: ‘A Russian counterpart to Mandela’

It is the funeral of the Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny today, after his death in prison two weeks ago. I’m turning to the South African Daily Maverick for the second time in a week. The editor, Branko Brkic, is clearly frustrated by the ANC’s close foreign policy alignment with Russia, and notes the recent “energetic participation of an ANC delegation, led by its secretary-general, at a ‘For Freedom of Nations’ forum in Moscow”.

Brkic says that Navalny is the Russian equivalent of Nelson Mandela, which might be a strong claim, but bear with it for a moment. To even start to make it, you have to get past Navalny’s right wing nationalism of a decade or so ago, so that’s where Brkic starts:

Navalny’s political views in his early days were not something I could ever agree with. He made a video disparaging Muslim immigrants, supported right-wingers and even supported Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014. But he moderated his nationalist leanings mid-career and admitted he had been wrong. In his manifesto from prison called “15 theses of a Russian citizen who desires the best for their country”, Navany, among other things, called for the country’s return to the internationally recognised borders of 1991.

(Alexei Navalny on a march in memory of politician Boris Nemtsov, killed in Russia, 16 May 2020. Photo: Michał Siergiejevicz.)

I’d missed this prison manifesto, but it is pretty unequivocal in its politics. It was posted on Navalny.com a year ago, on the even of the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Here are a couple of extracts:

The real reasons for this war are the political and economic problems within Russia, Putin's desire to hold on to power at any cost, and his obsession with his own historical legacy. He wants to go down in history as «the conqueror tsar» and «the collector of lands.»...

What are Ukraine's borders? They are similar to Russia's — they're internationally recognized and defined in 1991. Russia also recognized these borders back then, and it must recognize them today as well. There is nothing to discuss here...

Does Russia need new territories? Russia is a vast country with a shrinking population and dying out rural areas. Imperialism and the urge to seize territory is the most harmful and destructive path. Once again, the Russian government is destroying our future with its own hands just in order to make our country look bigger on the map. But Russia is big enough as it is...

We need to dismantle the Putin regime and its dictatorship. Ideally, through conducting general free elections and convocating the Constitutional Assembly.

We need to establish a parliamentary republic based on the alternation of power through fair elections, independent courts, federalism, local self-governance, complete economic freedom and social justice.

Recognizing our history and traditions, we must be part of Europe and follow the European path of development. We have no other choice, nor do we need any.

You can see that if you’re as much of a dictator as Putin, it would be irritating that someone you’ve already jailed can be as provocative as this, even if it would be hard for those Russians in Russia to access it.

Brcik notes that Navalny’s campaign against corruption became the vehicle for this transformation:

In this process of self-transformation, he became a modern-era politician with a platform of establishing a real democracy in Russia through the fight against corruption. There was a taste of this freedom in the chaotic days of Boris Yeltsin, but it never reached a period of normality where orderly daily life and democracy existed shoulder to shoulder.

And, sitting here in the comfort of London, you have to admire someone who was willing to put himself at risk so repeatedly for his politics: even before the novichok poisoning, or his return to Russia from Germany to face certain arrest, his right eye was injured after twice being sprayed by green dye by the authorities.

Some of Brkic’s admiration, I think, also comes from the effectiveness of Navalny’s corruption expose, Putin’s Palace, on YouTube and seen so far by 130 million people.

Should anyone from the ANC and its government care to learn more, they can easily find an exposé on oligarch Alisher Usmanov’s bribing of the former president and premier Dmitry Medvedev via a fishing retreat, as well as a delightfully funny exposé of another corrupt deal by the same players…These investigations are but a fraction of a much larger body of cutting-edge investigative journalism which exposed the epic scale of corruption schemes by Russia’s political and business ruling class.

Corruption is always the soft underbelly of dictatorships and failing political systems. I suspect that it’s not lost on South African readers that so many of the ANC’s leaders have had their own problems with corruption, of course. And part of this story is about the tragedy of the ANC’s long slide since defeating apartheid.

Brkic’s argument is that the point at which Navalny became “Russia’s Mandela” was when he chose to go back.

That was the moment when this extraordinary man left the realm of the normal and became a legend, a Russian counterpart to Nelson Mandela. He did not care about his physical safety or integrity — even as he knew that he would probably be killed eventually. But he also knew well that, with every day he spent outside of Russia as an émigré, the power of his ideas and beliefs would be further diminished. He knew firsthand the power of Putin’s propaganda machinery.

Between then and his death, of course, Navalny was subjected to a series of show trials, with ever increasing prison sentences attached to them.

In criticising the ANC’s loyalty to Russia—which seems to be based on the support that the Soviet Union gave to the ANC in its years of struggle against apartheid—Brkic points out that it’s not even good politics, let alone good realpolitik.

South Africa’s loyalty to the Russian president defies reason. And it is plain dangerous for our future. Putin and Co have built a citadel of violence and aggression. They are a main vector of international instability and by far the most bellicose player on the African continent... Believing that these people can be anyone’s friends is just plain wrong.

Navalny, he says,

will haunt Putin until his very last moment. The dictator may have built a regime that has crushed anything that even resembled democracy and accountability in Russia, but he won’t be able to rewrite his history.

Of course, in 2022, Navalny told a Canadian documentary that

"If they decide to kill me, it means that we are incredibly strong."

It’s possible to imagine, looking at the sheer weight of political repression in contemporary Russia, that this was whistling in the dark to keep yourself cheerful. Certainly a discussion on the Chatham House podcast about the effect of Navalny’s death on Russian politics, titled ‘Is This A Watershed Moment?’ was clutching for signs.

The one glimmer was the decision by his wife, Yulia Navalnaya, to step into the gap that has been left. Bill Browder, one of the contributors, observed that she had many of Navalny’s qualities, but also the “righteous anger of a woman whose husband has been murdered.”

He didn’t add this, but this is a deeply embedded metaphor in Russian and European culture—going back all the way to Greek tragedy.

2: Geoengineering climate change

It seems as if, sooner or later, as climate change gets worse, we are going to end up doing some geoengineering in order to try to buy ourselves some time. There’s a reason why both both Kim Stanley Robinson and Neal Stephenson have used geoengineering as a plot device in recent books. Just as there’s a reason why a distinguished climate scientist such as Sir David King has—knowing all the risks—suggested it might be necessary as a way to help re-freeze Greenland.

Why re-freeze Greenland, by the way? Because the alternative, in which the North Atlantic Conveyor shuts down, recently modelled by climate scientists, is utterly devastating. (And related, the University of the Arctic has produced a Compendium of Interventions to “slow down, halt, and reverse the effects of climate change in the Arctic and northern regions”.)

Of course, you only have to think about geoengineering for about ninety seconds to realise that it’s one of those technologies that calls forth the response, “what could possibly go wrong?”.

So it’s worth noticing that Switzerland has now proposed that the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) set up an expert group to

“examine risks and opportunities” of solar radiation management (SRM), a suite of largely untested technologies aimed at dimming the sun.

The proposal is being discussed at the current UNEP meeting in Nairobi:

A Swiss government spokesperson told Climate Home that SRM is “a new topic on the political agenda” and Switzerland is “committed to ensuring that states are informed about these technologies, in particular about possible risks and cross-border effects”.

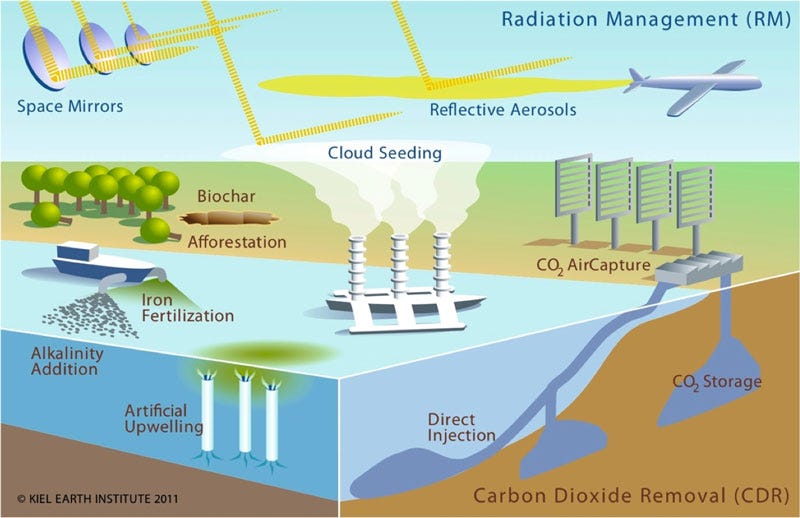

(A compendium of carbon reduction technologies. Infographic: Earth Institute 2011)

The Climate Change News report summarises reasonably crisply the arguments about solar geoengineering:

The technologies aim to reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the planet’s surface. This could be achieved by pumping aerosols into the high atmosphere or by whitening clouds. Its supporters say it could be a relatively cheap and fast way to counter extreme heat. But it would only temporarily reduce the impact of rising emissions, without tackling the root causes.

But the effects are largely unpredictable, both technically and socially. (There’s a reason why Kim Stanley Robinson and Neal Stephenson saw enough in there to write a novel around it):

The regional effects of manipulating the weather are hard to predict and large uncertainties over wider climate, social and economic implications remain. Solar geoengineering could “introduce a widespread range of new risks to people and ecosystems, which are not well-understood”, the IPCC’s scientists said in their latest assessment of climate science.

It found that the proposal divided scientists. On the one hand:

Ines Camilloni, a climatology professor at the University of Buenos Aires, welcomed Switzerland’s proposal, saying the UN “is in a good position to facilitate equitable, transparent, and inclusive discussions. There is an urgent need to continue researching the benefits and risks of SRM to guide decisions around research activities and deployment”.

On the other:

Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, head of climate science at Climate Analytics, says he is concerned about that prospect. “The risk of such an initiative is that it elevates SRM as a real solution and contributes to the normalisation of something that is still very premature and hypothetical from a scientific perspective”, he added. “You need to be careful about unintended consequences and consider the risks of opening a Pandora’s box”.

In fact, UNEP published a review of Solar Radiation Management by an expert panel last year—characterised as “an additional approach”—and a quick scan of the headlines in the executive summary captures the issues pretty well:

An operational SRM deployment would introduce new risks to people and ecosystems.

With many unknowns and risks, there is a strong need to establish an international scientific review process to identify scenarios, consequences, uncertainties and knowledge gaps.

A governance process would be valuable to guide decisions around research activities, including indoor research, small-scale outdoor experiments and SRM deployments.

SRM research and deployment decisions require an equitable, transparent, diverse and inclusive discussion of the underpinning science, impacts, risks, uncertainties and governance.

For me, this raises two related issues. The first is that almost all of these technology-based approaches to climate change tend to involve poorly understood technologies with unpredictably effects that typically are also hard to scale in the time periods that we have left to us to take climate change seriously.

In this respect, they contrast poorly with approaches to climate change that involve burning less fossil fuels and getting through less stuff, which are well-understood and have more predictable effects.

The other is that a lot of climate issues come back to governance in the end. The question, then, is how to have the governance conversation without somehow normalising the technology—or undermining the existing regulatory frameworks.

Switzerland has proposed this SRM expert panel to UNEP before, unsuccessfully, in 2019, and the opponents (and their rationale) make relevant reading here:

its attempt to get countries to agree to the development of a governance framework failed as a result of opposition from Donald Trump’s USA and Saudi Arabia – who didn’t want restrictions on geoengineering.

Last year, Mexico had to ban solar engineering after an American startup tried some “rogue experiments” on Mexican soil. The government statement said:

“Mexico reiterates its unavoidable commitment to the protection and well-being of the population from practices that generate risks to human and environmental security.”

And it’s also worth noting the group of concerned scientists who in 2022 signed an open letter calling for an “international non-use agreement” on solar geoengineering. Their argument underlined that there were risks at all levels—technical, political, and governance:

First, the risks of solar geoengineering are poorly understood and can never be fully known. Second... The speculative possibility of future solar geoengineering risks becoming a powerful argument for industry lobbyists, climate denialists, and some governments to delay decarbonization policies. Third, the current global governance system is unfit to develop and implement the far-reaching agreements needed to maintain fair, inclusive, and effective political control over solar geoengineering deployment.

In short, it is not just the technology that is poorly understood. Governance is (deliberately and necessarily) a slow moving beast. It would take years to be comfortable that the right controls were in place to ensure that the technology didn’t go rogue.

j2t#547

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.