07 December 2022. Circular economy | Advertising

Making the circular economy work. // Giving up on social media advertising.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Making the circular economy work

I was pleased to get an invitation to a seminar organised jointly by the University of Cambridge and the University of Tokyo earlier this week, and elected to join the session on the circular economy.

It was a useful chance to catch up on current thinking in the area. Steve Evans, of Cambridge’s Institute for Manufacturing, kicked it off with a presentation on ‘The circular economy 10 years on: what are the challenges’.

I wasn’t completely sure about the ‘10 years on’ framing, since the phrase goes back to 1988. I first came across the concept, if not the name, in McDonough and Braungart’s book Cradle to Cradle in 2002. Their definition is still pretty good:

Everything is a resource for something else. In nature, the “waste” of one system becomes food for another. Everything can be designed to be disassembled and safely returned to the soil as biological nutrients, or re-utilized as high quality materials for new products as technical nutrients without contamination.

Evans structured his talk around three questions:

What’s positive?

What’s negative?

What are the challenges?

Under ‘positive’, the phrase is understood, across industry, education and policy-makers, and to some extent in business. There’s been a big increase in the number of people doing research in it. And there have been big steps in designing circular business models and circular pathways for materials.

Under ‘negative’, most of the companies doing this work are start-ups and small organisations, not big companies. Big companies are doing design, but not much in the way of implementing and testing. This is also a challenge: it’s hard to test circular economy flows until they are operating at scale, so we need to improve our ability to test.

Under challenges, there are co-ordination issues—circularity typically involves co-operation between businesses in different sectors. We still end up having to discard some of the materials in high performance products, such as steel. We understand how to deal with the iron, but we end up discarding the 2% made up of other elements that are in there. That’s related to a further challenge—we still have a limited understanding of the material flows in the economy.

The future of this might lie in biology:

We need increasingly to replace technical materials with biological materials, and that is already happening.

Dr Takanari Ouchi, of Tokyo’s Institute of Industrial Science, provided an example of some of the ways these innovations work in practice.

He used the example of recovering gold, which is currently a heavy industrial process involving “strong solutions” such as chlorine and cyanide, it takes a long time, and produces a large amount of hazardous liquids.

An innovative process involving dissolution in molten salts is simpler and shorter, and produces no hazardous wastes. In other words, it is better and cheaper, which should mean that it will be adopted sooner or later.

(Source: Dr Takanari Ouchi, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo)

Both men referenced the ‘famous’ butterfly diagram developed by the Ellen MacaArthur Foundation on how to improve circularity, which also reminded me of the importance of creating common terms of reference when you’re trying to create change.

(Source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation)

These models are valuable but largely technical Dr Anna Barford, of Cambridge’s Institute of Sustainability Leadership, is working on how you make the circular economy socially sustainable as well.

Because, as with AI, these systems all have cheap labour buried within them. Barford shared work on waste-pickers in a number of countries in the global South that she has done with her colleague Saffy Rose Ahmad

(Hierarchy of plastic recycling. Source: Barford and Ahmad)

Big companies are starting to make commitments to recycling plastics, although the value of this is limited. Recycling is the least valuable part of the circular economy. All the same, it is possible to re-valorise the work that the waste-pickers do, and ensure that they and their families are enrolled in health and social systems. Puma has been pioneering a scheme along these lines with First Mile in Haiti.

(A socially restorative butterfly for the circular economy, based on the Ellen MacArthur Foundation Butterfly Diagram. Source: Barford and Ahmad).

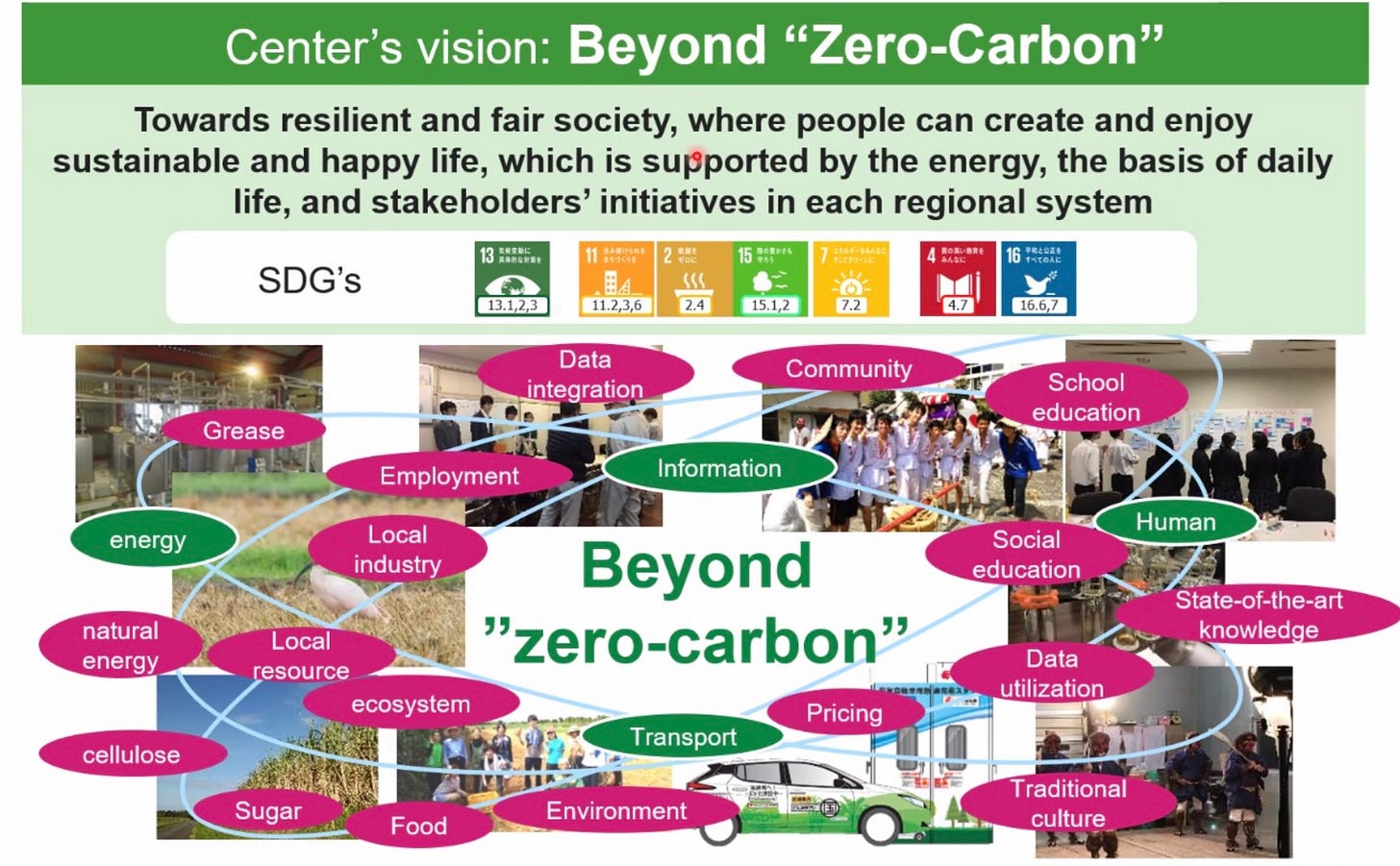

The final speaker was Dr Yuko Oshita, of Tokyo’s Institute for Future Initiatives, who shared a 10-year project called ‘Co-JUNKAN’, exploring how circularity works at a local level as part of a wider ‘beyond zero-carbon’ project. (‘Junkan’ means ‘circulation’ in Japanese).

The project starts from the operating principle that "Zero Carbon" is just a subset of social sustainability goals, which includes sustainable regional transport, stable food production, the maintenance of ecosystems, energy security,

ecosystem, and attractive livelihood and its infrastructure, illustrated by a rather busy slide from her presentation.

(Co-JUNKAN. Source: Dr Yuko Oshita, of Tokyo’s Institute for Future Initiatives)

In their research with local communities so far, they have found that the narrative around the reasons for the circular system are as important in creating change as the technical aspects of the work. But perhaps that shouldn’t be a surprise.

2: Giving up on social media advertising

The advertising and marketing site The Drum has a story about the personal care retailer Lush, and the consequences of its decision to kill its advertising spend on some social media sites a year ago.

TL:DR? There aren’t that many consequences.

(Lush cosmetics store, Brent Cross, London. Photo by Philafrenzy via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

But the article, which is basically an extended interview with Lush’s brand and marketing director Annabelle Baker, is interesting on what made Lush take the decision, and how they managed the possible marketing impact:

(T)he final straw was Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen exposing the extent to which Meta knew its products were damaging teenagers’ mental health and spreading misinformation. The volume of people being harassed, abused and negatively influenced was too much to ignore. So Lush quit.

It was a surprising decision, at least inside the marketing community, although Lush had already noticed less engagement with its users on social media, and fewer people coming to the brand through social media. As Baker says:

From a digital marketing point of view it had been a great way to reach customers, but the algorithms had been making that harder and harder. Especially when you don’t pay to play. Even before we made the decision for the reasons we did, social hadn’t been delivering for us.

A year on, of course, she feels vindicated: Twitter in meltdown, Facebook/Meta struggling, TikTok’s data policies being scrutinised.

All the same, the move did cause some immediate problems. In particular, customers had got used to messaging Lush, for information or with complaints, on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook. The company has set up a Live Chat function to fill this gap, which involved taking on staff, and plans to launch an SMS function as well.

It also left something of a hole. Lush had 12 million followers across the social media sites. It has set up Bathe, a self-care app which it describes as being the ‘antithesis’ of social networking, and investing in more presence in its retail stores, including more experiential events, although that is a slow build.

It’s hard to compare numbers, because of the pandemic: retail sales are up year on year (comparing 2021 figures with 2020), online sales are down. But it has involved spending more on marketing, because social media is so cheap in comparison.

And Lush hasn’t come off social media completely. You can still find it on Pinterest and YouTube. These platforms have also had problems, but Baker’s criterion here is whether they are taking moderation seriously:

While Meta has failed to convince her that they are taking moderation seriously, YouTube and Pinterest have. “We are in conversations with Pinterest and it has been really interesting to learn what they have been doing in the last couple of years to make that platform safer,” she continues. “We’ve looked extensively over the past few months at YouTube’s moderation. It’s huge. It’s not catching everything, but it is catching significant volumes of harassment and hate. That’s what we want to see as a brand – no platform is perfect, but we need to see the processes in place.

Baker says that Lush is unlikely to return to Facebook, which is

a site “that feels like it’s dying anyway.”

She might have been willing to reconsider Instagram, but she changed her mind when she saw how different platforms responded during the inquest into how social media had played a role in the death of teenager Molly Russell.

“You can see all of the steps Pinterest put in place. But everything Meta did ... there was nothing encouraging about wanting to be back on that platform. If it had handled the situation differently, like Pinterest, then we would be open to looking at (Instagram) again. But it did the opposite. It was insulting to the family.”

Lush might be an outlier, but this is the kind of thing that happens when platforms start to decline. Revenues are falling, so platforms with less concern over their social permission to operate are more careless about restrictions on users that might depress their margins, which creates risk in their relationships with companies concerned about their reputation.

Lush’s audience is also mostly women, who are more likely to care about the impact of social media on the health of children, and, come to that the widespread—and largely unmoderated—misogyny on social media platforms.

So maybe there’s also a wider point here. In moments of social dislocation, brand-building is about being able to demonstrate to your customers, visibly and credibly, that you are on their side. Sure, the product has to work, but that’s just table stakes.

Baker, by the way, has no time for brands who halt advertising on a social media platform for the duration when a platform becomes a hot topic. She says that’s “just performative”. They should be more worried about the overall impact of social media platforms on their customers, she says.

j2t#404

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.