7 April 2023. Sustainability | Campaigning

Making business sustainable // Taking the economic crisis onto the streets

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear [on my blog] from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Have a good weekend. There may be an edition on Easter Monday.

#1: Making business sustainable

I went last week to hear the futurist and sustainability adviser David Bent talk on ‘business policy and transformation’ at the Bartlett School in London. David worked at the Forum of the Future for a decade or so, and these days mixes up some teaching with advisory work. The slides from his talk—some of which will be threaded through here—are on his website.

There was quite a lot in his talk, and so I’m going to try to pull out some themes rather than try to recap the whole thing here.

From CSR to ESG to ‘purpose’

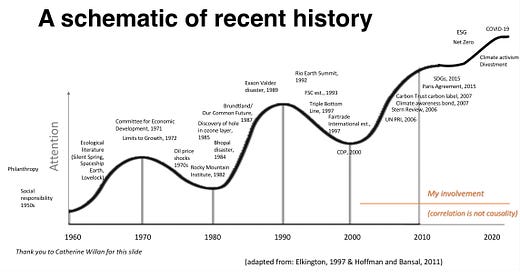

It’s possible to be gloomy about the progress of ‘sustainability’ as a business idea, but it’s also clear that as the climate emergency has become more imminent attention has been increasing. David’s characterised his engagement, over the last 20 years, as corresponding to three ages of awareness. The dates here may be approximate.

The first, from 2003–when he started doing this work—to 2006, was about stopping your negative impacts, and taking responsibility for your externalities. The second, from 2006 from 2013, was about ‘the issues will come and get you’. The third, from 2013 to now, and I’d say still continuing, is about ‘system change not climate change’. Knowledge has deepened and activity has become more urgent and more political, even inside businesses.

He also characterised this with a couple of quotes: the first era was marked by a partner at the accounting practice where he worked in the early 2000s asking ‘what is this climate change?’. The third is that ‘Net Zero is everywhere’, and that ‘our commercial success relies on this’.

In the middle, somewhere, he told a story about a Pepsico executive upbraiding him when he was at Forum for the Future for what they regarded as sloppy scenarios construction. Scenarios were supposed to be different, he complained, but “You have climate change in all of your scenarios.” (It’s easy to miss the idea of ‘predetermined elements’ if you think that scenarios are all about uncertainty).

Where we are now is that governments that understand the risks of climate change are just starting to create policy frameworks—if imperfect ones—that enable progressive businesses to act. This is the idea behind ‘mission-driven’ policy. This then unlocks investment and growth that reinforces the policies. (I’m not including the British government in this, given their lamentable performance on so-called ‘Environment Day’. Being captured by the fossil fuel industry is not a good look in 2023.)1

Getting to transformation

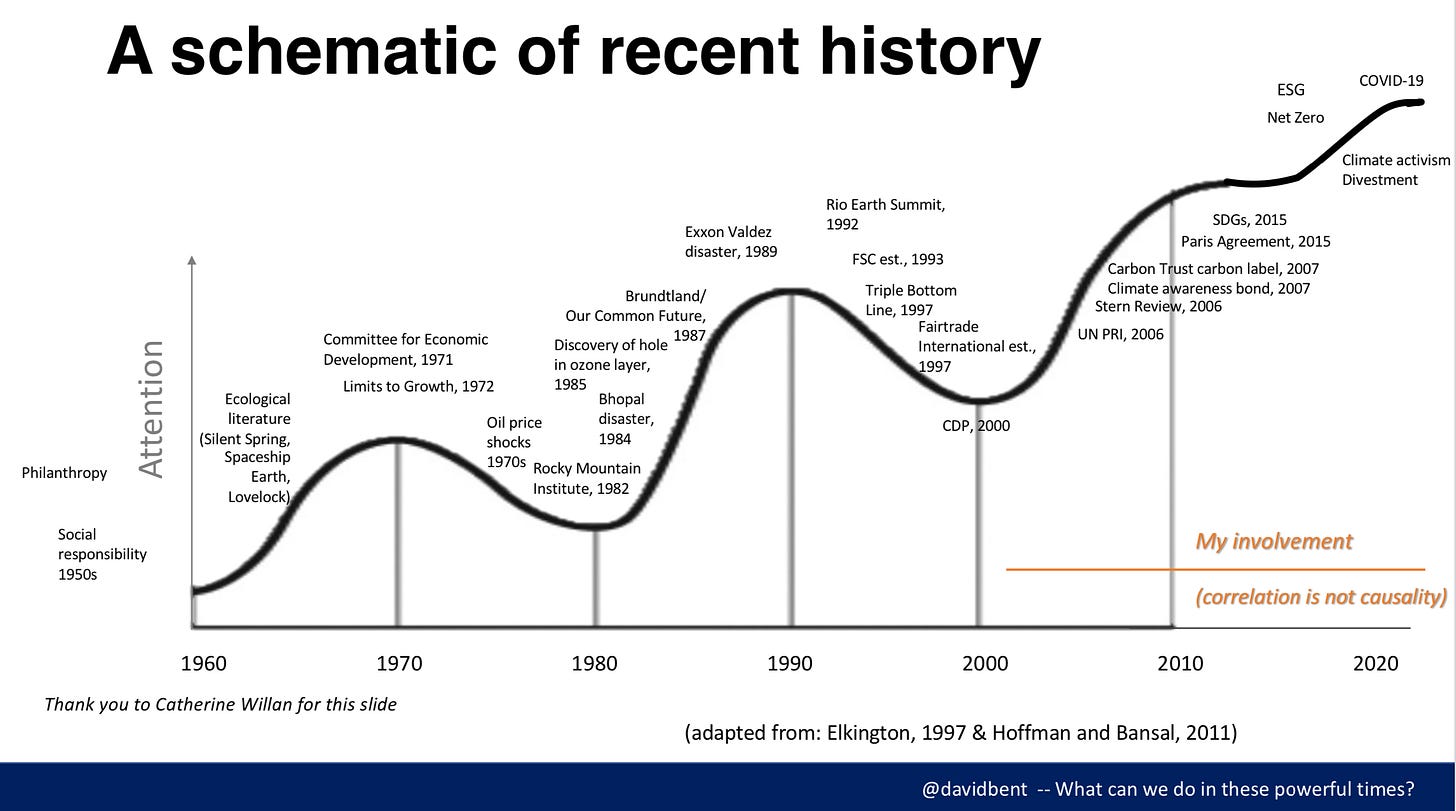

Separately, David and I have had the same intellectual journey about scenarios and uncertainty, as it happens, both from thinking about Jim Dator’s ‘alternative futures’ scenarios archetypes. The archetypes are ‘Growth’ (here called ‘continuation’; ‘transformation’; ‘discipline’; and ‘collapse’, shown here in an adapted version produced by the Foresight University.

Looking at the future through this lens, there’s not much uncertainty at all. ‘Growth’, in a world of limits, either gets stuck in the ‘Discipline’ scenario, which is usually about constraints to limit adverse impacts, or it goes to Collapse. Discipline is also constantly at risk of collapse. The only scenario that gets you through to an increasingly narrow pathway to a sustainable world is some kind of version of ‘Transformation’, as any reading of the recent IPCC reportreminds you. Scenarios aren’t about uncertainty any more. They are about understanding the options that get you to that path.

And one of the things I took away from the remarks from businesses about ‘Net Zero is everywhere’ and ‘our commercial success depends on this’ is that businesses understand this intellectually and emotionally, even if, in most cases, their systems and underlying dynamics haven’t started to catch up yet.

I took this as an encouraging sign, in that when that kind of a gap opens up between what people say, think and feel, and the actual outcomes of what they do, change can happen quite rapidly once it begins.

So what do businesses do?

The other thing that I found encouraging was that there is no shortage of ideas about how businesses should adapt, a veritable Cambrian explosion of models and frameworks. David threw a whole set of these up on some slides, noting that the academic ones tended to be more robust but the business ones were more colourful.

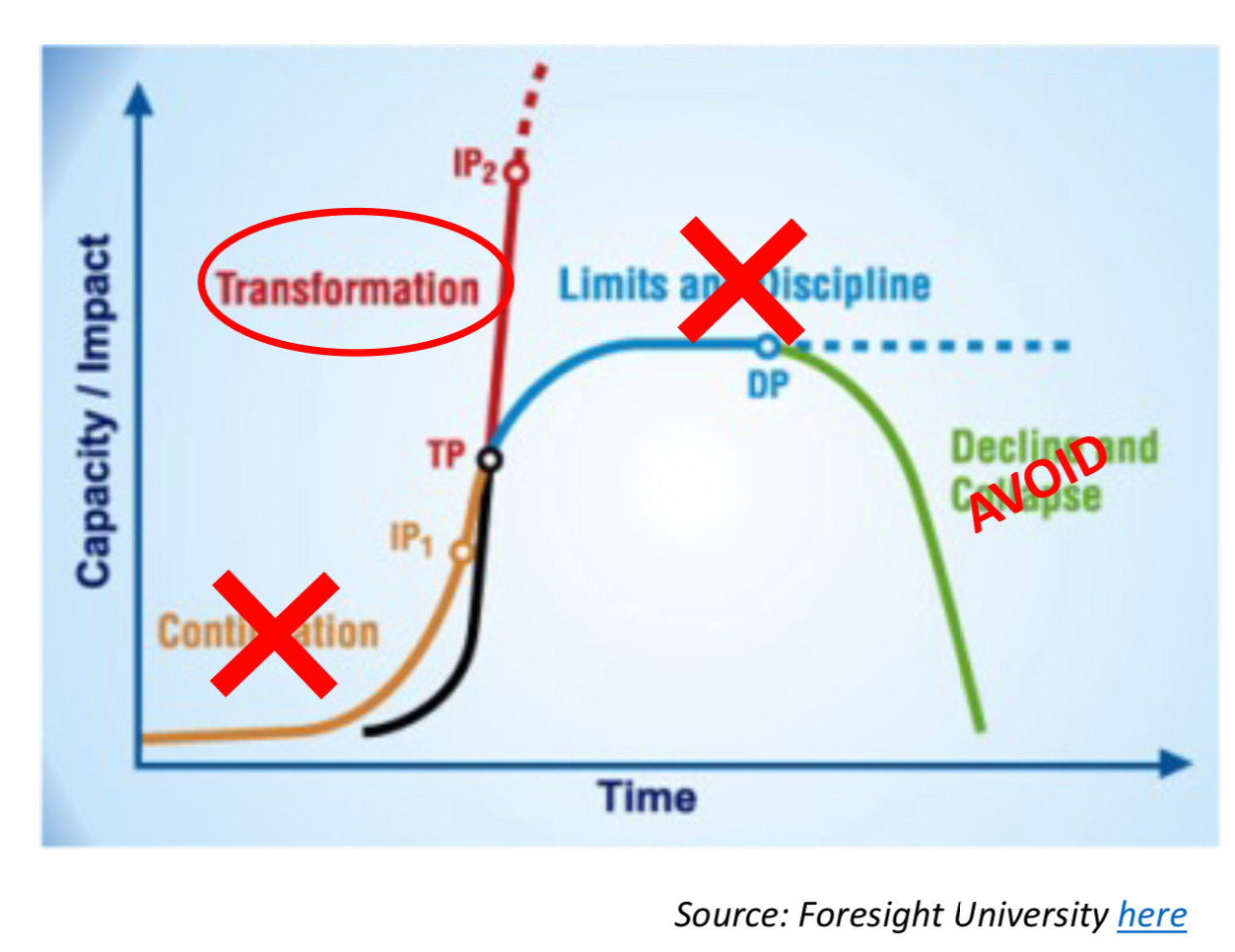

But the framework he paused on was David Snowden’s Cynefin framework, which in its current iteration is built around five domains which each start with C: Clear, Complicated, Complex, and Chaotic, with a ‘Confused’ domain in the middle where different types of system interact and need to be untangled.

(Source: David Snowden)

The implication of this is that businesses need to explore new practices, or adapt existing ones to new ends (which is what is meant by the ugly neologism ‘exaptive’). My perspective on this is that businesses—especially large ones—aren’t very good at doing complex. They were mostly built in the days when the external environment was less turbulent, and you could get by being complicated.

The trouble with complexity is that it requires (in Ross Ashby’s framing as the law of requisite variety) businesses to increase the amount of ‘variety’ they are able to absorb. Businesses that are merely good at doing complicated will break under the strain—or simplify the way they do business. A more pessimistic way of reading the plethora of models and frameworks about business transformation is that businesses just don’t know how to manage a complex and turbulent environment.

Building a new model

But let’s not get too depressed too quickly. David offered some hypotheses about the changing environment that I’m going to reproduce here on his slide rather than type them all out.

Some of these might be thought to be controversial. We’ve all had drummed into us that democracies can’t deal with crises because politicians want to be re-elected, although the pandemic maybe demonstrated that they can deal with crises but at the last minute.

Incumbent businesses, with easy access for lobbying purposes, tend not be fans of anti-monopoly. So far, we’ve seen populists tell a story that’s easier to understand about security and control than the kind of story more progressive politicians have to weave to connect security with a more inclusive politics. Again, there’s some literature now on mobilising around positive stories than negative ones. And so on.

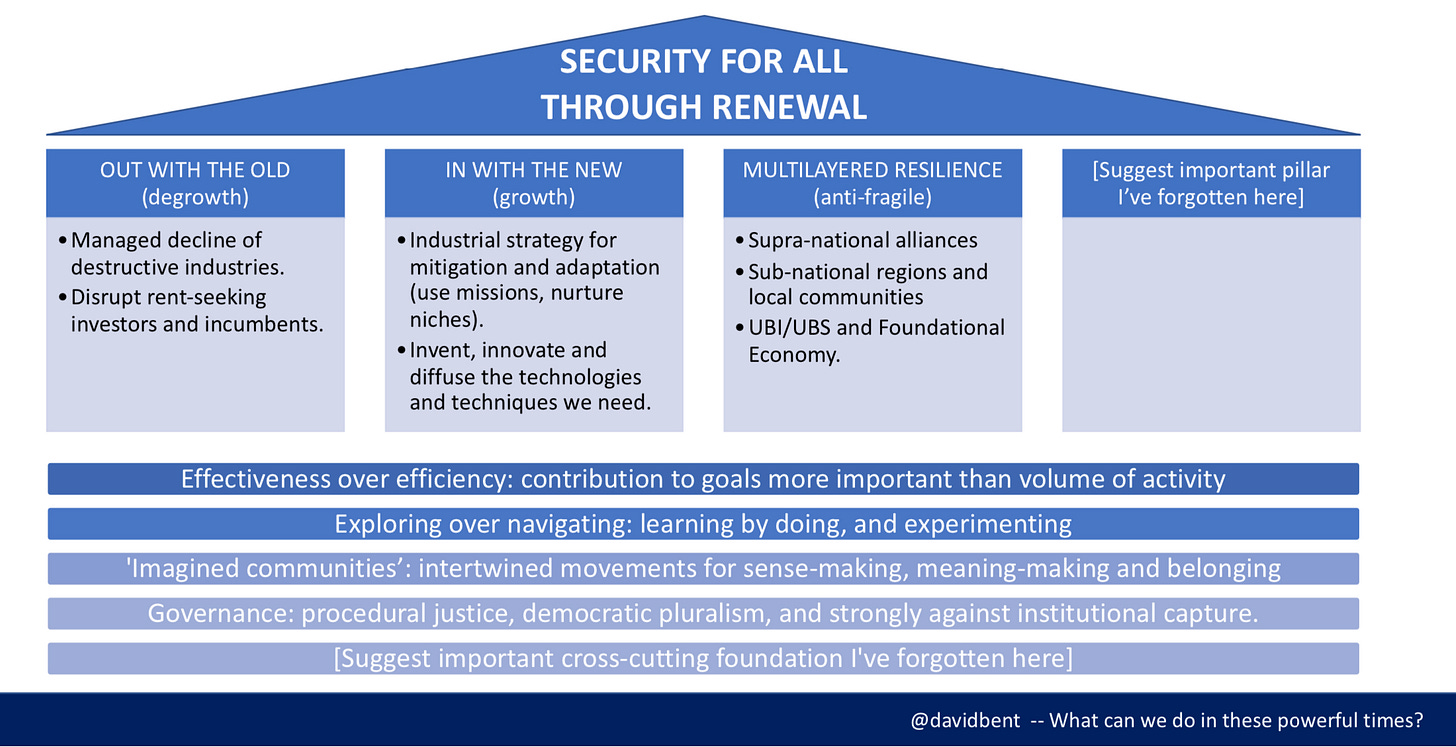

All the same, in this turbulent world of climate change, security will be at the heart of the story, so progressive politicians need to get onto this story quickly. David’s final proposition was a draft version of what some of this might look like—headed, I should add, ‘wrong but hopefully useful’.

(Source: David Bent)

There was some discussion of this idea of ‘security’ in the discussion afterwards, which turned out to be a bit of a testimony to how the word has been captured by the right and associated authoritarians in the last 80 years.

One of the ideas that emerged from the scenarios work I did with Chatham House on post-Ukraine war futures last year was that government are already under pressure to revalorise the idea of security so it includes food and energy, rather than just being about personal safety. In this, governments become more important—something that governments in the post-World War II world have understood immediately. One of the long wave patterns in futures work, associated with Strauss and Howe, is that we go from ‘crisis to crisis’ in around 80 years. Rebuilding—based on new ideas and different values—follows the crisis, so maybe the timing is about right.

Businesses also have to choose, as well, of course. At the moment they are in a fight between their investors and the pursuit of short-run returns, and their employees and customers, who would rather they took a longer term-view. More effectiveness and less efficiency, to borrow a line from the diagram above.

Which reminds me that I did some work on this very question a couple of years ago that I haven’t shared. I’ll come back to that next week.

#2: Taking the economic crisis onto the streets

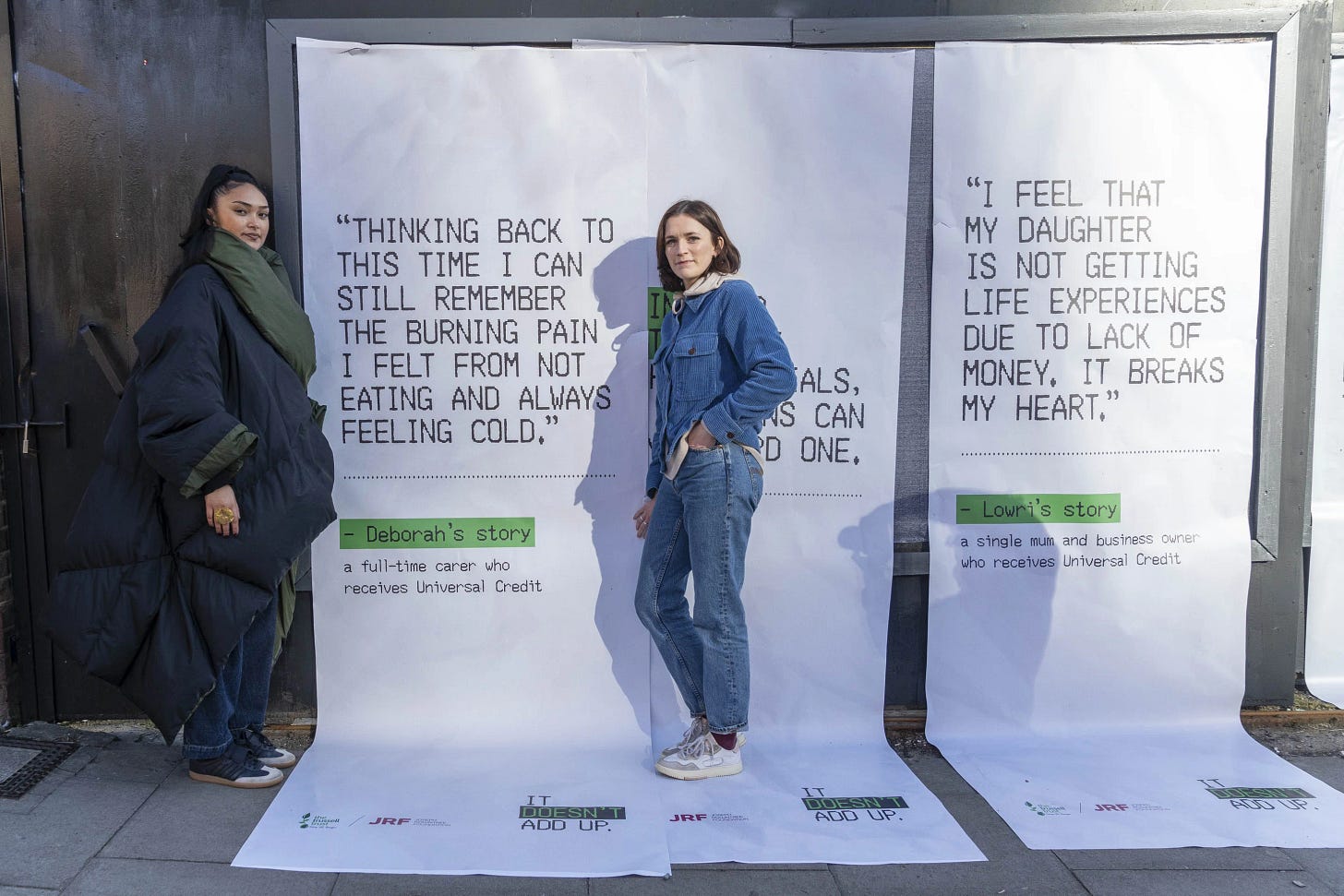

That was long, so this will be short. A campaign by the creative agency Don’t Panic, and NGO and charity The Trussell Trust, has turned a billboard in Finsbury Park into a till. The intention is to build support for the Essentials Guarantee—a new UK campaign that asks the government to close the gap between what individuals and couples are paid on Britain’s Universal Credit system.

The story is on the art and design blog It’s Nice That.

The sums first, then the creative:

The Trussell Trust and Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) – the independent social change organisation – have calculated that a single person in 2023 needs £120 a week to afford essentials after housing costs while a couple needs £200. The Essentials Guarantee shows that the standard allowance is falling almost 50 per cent below this amount in some cases. The JRF report finds that 90 per cent of low-income households on Universal Credit are currently going without essentials.

(It Doesn't Add Up. Copyright © Don’t Panic / The Trussell Trust, 2023)

The poster has a printer embedded in it which will print out huge receipts at the site, to show the shortfall between the basic rate of Universal Credit and the cost of essentials. It will also print quotes from real people. Some of these will be flyposted at other sites in the area.

The agency, Don’t Panic, hopes that by using real stories and real till rolls it will bring home the scale of the issue.

Emma Revie, the chief executive of Trussell Trust, explained the campaign like this:

“This giant till roll makes it impossible to ignore the fact that the cost of even just essential items is surpassing the amount that hundreds of thousands of people in receipt of Universal Credit must live on each week. We want everyone who sees it to stop and think about how they would cope if they had just £85 a week to live off – you quickly realise that it just doesn’t add up.”

(It Doesn't Add Up. Copyright © Don’t Panic / The Trussell Trust, 2023)

----——————————-

j2t#443

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

I know I also mentioned this earlier this week, but leadership matters.