7 February 2023. Cities | Politics

The end of the global city story. // Britain and ‘Shit Life Syndrome’

Welcome back to Just Two Things, after my break. I try to publish this newsletter daily, three times a week, but don’t always succeed. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

Schedule news: This week’s Just Two Things will be published on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. I’m also starting a course this week for the next two months, which means that while I’m doing that, the Friday edition will move to Saturday. I may do a bit more on culture while it’s in a weekend slot.

1: The end of the global city story

I’m talking later today at a conference in Cardiff on the future of work. This is the first of two posts based on that talk, one on cities, one on the implications for work. I approach the future of work through the lens of the future city, since the shape and structure of work is bound up more or less completely with the shape and structure of cities.

Edward Glaeser’s book The Triumph of the City (2012) gets a lot of love in these conversations. It’s hard to find people who have a bad word to say about it. In the presentation, this was the quote that I pulled out to illustrate his version:

Cities are the absence of physical space between people and companies. They are proximity, density, closeness. They enable us to work and play together, and success depends on the demand for physical connection... And during the last thirty years... technological change has increased the returns to the knowledge that is best produced by people in close proximity to other people (p6).

The first half of this seems like a description for the ages—the city as experienced in Roman times, or Elizabethan England, would match this description. The second half is actually more contentious. The phrase “the last thirty years” is a bit of a giveaway. Because what he’s actually describing in his book is not a general model of the city but a particular one—the version of the city that has emerged through a combination of technology, globalisation, and the growth of services as the overwhelming share of modern economies.

In this model, competition between cities happens at a global level, and represents competition for high value added companies, mostly in the tech and finance space. There’s two elements to this, one of which is endlessly discussed, and another which is overlooked.

The endless discussion: that if companies can be based anywhere, no longer tied by raw materials or sunk industrial capital, then they will go somewhere—and the somewhere will be the places with big pools of labour and also some corporate prestige. (As we discovered when New York told Amazon it wouldn’t subsidise its new headquarters building, while other cities would, and it decided to go to New York anyway.)

(Google Ireland. Photo by Outreach Pete. CC BY 2.0 http://www.outreachpete.com/)

The overlooked: the returns to knowledge that Glaeser discusses are as likely to be the result of extraction and rent-seeking as from higher productivity generated by all that close proximity. (There’s a telling passage in Glaeser—p5, if you want to look it up—where he extols without irony or self-wareness the fact that 1980s New York produced financial innovations such as Michael Milken’s junk bonds, and Henry Kravis’s debt-funded leveraged buy-outs. That is the same Michael Milken who is now a model citizen having served 22 months in jail for violating US securities laws.)

So maybe this model is less impressive than it looks. And it may also be a feature of a particular moment of capitalism.

If you want to do this from first principles, you need to look at the Santa Fe physicist Geoffrey West, whose book Scale developed a theory of how cities work. His starting point was a finding from the data that says that a city in any given country that is twice as large as another city produces 15% more of everything—wealth, yes, but also crime, illness, etc. It also does it on 15% less infrastructure. These are interesting numbers.

The second startling fact in the book is the amount of energy humans get through in cities. In the pre-industrial age, humans would get through about 100 watts a day each. Now, they get through 11,000 watts. The ecologist Herbert Girardet has a striking image related to this: that Europeans have the equivalent of 60 full-time ‘energy slaves’ on tap, Americans, 80 ‘energy slaves’.

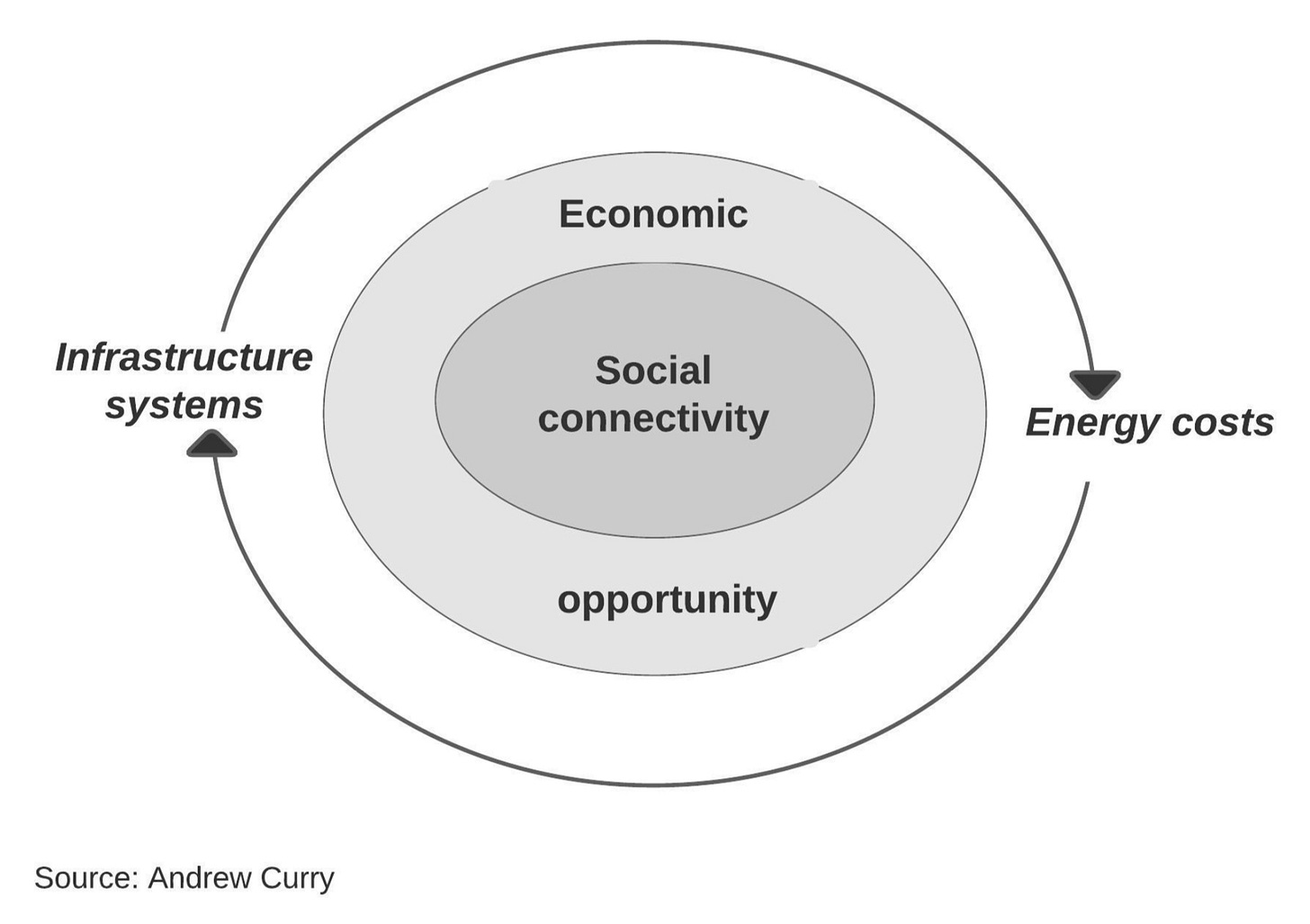

West’s model therefore starts from energy and infrastructure, which he says drives social connectivity and social capital. From the interaction between these comes economic opportunity. I developed a simple schematic that tried to link these together (West in not to blame for this diagram).

(Geoffrey West’s urban model, visualised by Andrew Curry. CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

West was born in Britain, but perhaps has been in the US for too long, because he says that this economic layer is driven by “greed”. But the data he quotes don’t say this. Regardless of city size, a new business is created for every extra 22 people in the city, and these businesses employ, on average, eight people. That doesn’t sound like greed to me, more like people making a living.

The problem with Glaeser’s glittering economic version of the city is that it is almost completely dependent on fossil fuels to bring in the resources it needs to survive. All of these global cities have a vast global footprint. Girardet, again, calculates that London has an ecological footprint 125 times its size, pretty much the equivalent of all the productive land in Britain.

In their book, How Everything Can Collapse (2020), Pablo Servigne and Raphael Stevens say:

The paradox that characterises our era… is that the more powerful our civilization grows, the more vulnerable it becomes... To preserve ourselves from serious disruptions to the climate and the ecosystems... we need to turn off the engine (p88).

These cities are no longer working at other levels, either. They are also failing to reproduce themselves, in that sense that they struggle to provide adequate care for their young, their sick, their elderly. Increasingly they are also unaffordable both for their essential services workers, and for the generation of young workers that historically would have represented the next generation of managers and entrepreneurs. All of this has been exacerbated by the increases in housing costs caused by deregulation of the financial system and asset inflation that has benefitted the wealthy at the expense of everyone else.

So it’s possible to imagine that the city that Glaeser described in his book was not the city of the future, but a city that was already sliding into the past. If this is true, it has significant implications for the future of work. I’ll come back to this in the next Just Two Things, which will be on Thursday this week.

2: Britain and ‘Shit Life Syndrome’

The economist Diane Coyle has on her blog a pocket review of Paul Johnson’s new book, Follow The Money: How Much Does Britain Cost?. Paul Johnson is as mainstream an economist as you get in the UK—long-standing Director of the Institute of Fiscal Studies, CBE,1 and so on.

Coyle describes the book as “a calm, even forensic account” of the trade-offs involved in delivering public services, but reports that it left her furious:

We know – don’t we – that governments do a lot of stupid things, badly. We’ve certainly had a run of these stupidities here in the UK: Brexit on the worst possible terms for internal party reasons, Liz Truss… Even so, to see collected in one place all the bad decisions concerning the fundamental well-being of citizens is angry-making. Any unavoidable choice that could be postponed has been, even at substantial long term cost. There have been obfuscations and lies. And it has been going on for years.

One of the obfuscations is about the economy. Ministers talk brightly about “growth” when in the actually existing economy growth is running at a dismal 1%, down from an already miserable 1.7% per year in the decade from 2010-17, and is currently trending down towards zero. Britain’s inequality is shocking, as she says. And’ although she doesn’t mention it, the public realm is falling apart.

I’m going to park here for the moment the question about whether we can afford economic growth in an age of climate emergency, since the first answer to that is that it depends on how you get to your growth, and the second is that if we are going to invest more in public services we need a higher tax base, and even if a government decides to tax the rich, on income and assets, until the pips squeak, we’re going to need a stronger economy to pay for it.

Coyle observes, strikingly, that part of the problem here is that politicians have lost touch with how their constituents live. (This might be down to the professionalisation of politics in general, or the specific phenomenon of very wealthy Conservative cabinet ministers):

As Simon Tilford noted in a recent essay , most of the people taking decisions have no idea about the lives of those they exercise control over, about how badly off most of their compatriots are. The over-burdened welfare state is not quite coping with people suffering from what (I learned here) doctors describe as “Shit Life Syndrome” when they go to their GPs for help with depression or other mental ill-health conditions. And there will not be enough money to fix any of this unless growth picks up. But that would require a competent, effective government able to take clear decisions, build cross-party consensus, devolve money and powers, and stick with the plan.

I’ll be interested in taking a closer look at Johnson’s book later on, although the bromide that Coyle quotes doesn’t inspire confidence:

We can, and must, do better.

There is a big unspoken question in British politics at the moment. This is why the British state is completely incompetent (certainly when compared to a raft of other governments) in building skills, capacity and infrastructure, and the effect this has had on long-run productivity and therefore on incomes and public spending. Politicians tend to avoid it because it is a long-term problem, and hard to fix, but not impossibly hard. I take this book and maybe this review as a sign that this question is perhaps starting to move up the public policy agenda.

j2t#421

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Commander of the British Empire. A prestigious gong, in other words.